Border Carbon Adjustments 101

An introduction to border carbon adjustments, their components, benefits and costs, and the role of the World Trade Organization in their implementation.

What is a Border Carbon Adjustment?

A border carbon adjustment, or BCA, is an environmental trade policy that consists of charges on imports, and sometimes rebates on exports. BCAs reflect the regulatory costs borne by domestically produced carbon-intensive products but not by the same, foreign-produced products. While domestic policies in many nations apply regulatory costs to other greenhouse gas emissions, the trade focus has largely been on carbon dioxide.

Several different phrases are often used to refer to essentially the same idea. Border carbon adjustments (BCAs), border tax adjustments (BTAs), and carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs) all refer to this notion of imposing a cost equivalent to domestic climate regulatory costs on otherwise unregulated imports.

The goals fueling BCAs are twofold: to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and to avoid the emergence of trade advantages and disadvantages as different governments enact climate policies with different levels of ambition. As of this writing, no BCA has ever been fully implemented—the policy option is still theoretical.

A BCA is a policy option that exists in the absence of a global, harmonized carbon pricing policy and/or an international agreement on how to deal with these issues. It’s a way to support a level playing field by making foreign importers face the same costs and incentives to mitigate carbon that domestic producers face. By discouraging production from moving abroad to less regulated jurisdictions and then exporting back to the more regulated jurisdiction, a BCA protects the climate mitigation ambition and the domestic industry of the country enacting it.

The core idea behind a BCA is to prevent emission “leakage” related to competitiveness effects. In this context, this includes the potential for increased emissions in countries without (or with less ambitious) carbon mitigation policy compared to other countries that put forth more ambitious mitigation plans. These incentive misalignments between trading partners reduce the net effect of an ambitious country’s policies and could even end up increasing overall emissions.

Note that in the literature, “leakage” can refer to emissions leakage related to both (a) competitiveness effects, where jobs and industrial production shift because of changes in the cost of manufacturing goods, and (b) shifts in energy use because of overall global changes in price of fossil fuels.

Like the core ideas behind them, BCAs’ impacts span two main outcomes: emissions and trade. Emissions outcomes are understood through two types of research in this area: modelling and empirical analyses. While the scale of emissions changes varies through the literature, meta-analyses show that BCAs reduce carbon leakage rates roughly in half, approximating the share of competitiveness effects relative to total leakage.

Trade outcomes tell a similar story. When experts look at scenarios with and without a BCA, the BCA appears largely protective of competition and free trade.

Important Components of a Border Carbon Adjustment

Establishing Scope

An important step in crafting a BCA is considering what emissions to include under the policy. Discussions often refer to three main “scopes” that include varying levels of direct and indirect emissions produced by a product:

- Scope 1 only targets direct emissions from the production of goods and services.

- Scope 2 encompasses emissions created from purchased energy.

- Scope 3 encompasses emissions created from purchased products (not energy) and, in the case of fossil energy products, possibly from downstream combustion of the product.

Emissions assigned to facilities must then be assigned to the various products that facility creates. A BCA would apply only to a subset of those products, presumably based on exceeding a minimum threshold for this emission intensity (and potentially other factors).

In one approach, RFF research introduces the idea of a greenhouse gas index for manufactured goods. This metric would track taxed sources of greenhouse gas emissions required to produce specific products—namely, emissions by the manufacturer and those associated with covered products purchased by the manufacturer. If applied based on a tax, this administrative tool could be an effective way to calculate emissions and border obligations compatible with the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) rules. You can read more about the WTO below.

In addition to establishing the covered commodities and their emission intensity, decisionmakers must determine how much additional cost importers will face, and what—if any—export rebates will be allowed. This relies on an established price per unit of carbon.

Accounting for the Cost of Carbon Emissions

In practice, and in much of the modeling literature, the implementation and analysis of BCAs is anchored by a national carbon tax or other policies tied to an economywide carbon price. That is, BCAs are very often discussed in terms of a comprehensive carbon tax, despite the much broader range of polices in practice. BCAs are easier to understand in this framework since they would ensure that foreign producers face the same clearly defined incentives and costs to reduce emissions as domestic producers.

Being able to contemplate a BCA without pricing carbon–if countries indeed pursue ambitious policies through other means—might allow more countries to use BCAs and allow countries with carbon price-based BCAs to “credit” those with non-price policies. Considering that not all ambitious climate mitigation policy is tied to a comprehensive carbon price, the opportunity to widen BCAs scopes could continue to help with concerns of leakage and competitiveness.

In a 2021 working paper, RFF scholars William Pizer and Erin Campbell Coauthors of this explainer propose mechanisms for such expansion. In practice, this would involve taking the difference between the importer and exporter’s effective charges. In a way, this translates non-carbon-price policies into a carbon-price-equivalent value for the purpose of leveraging the same costs and incentives across borders. This would likely be challenging in practice from the perspective of administrators to establish and uphold such an accounting procedure.

Implementing Import Fees and Export Rebates

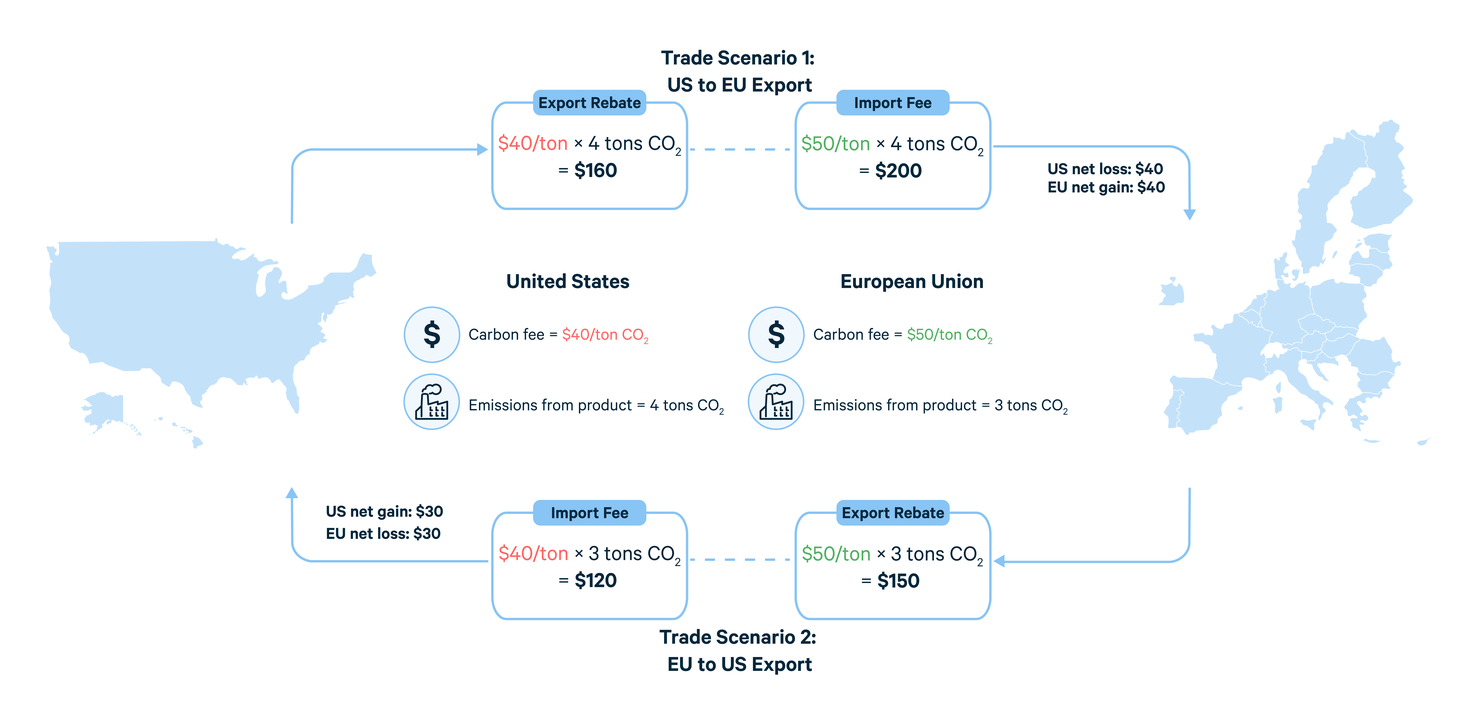

The import fee, which is applied by the nation in which the product is sold, prevents foreign producers from avoiding the emission reduction costs levied on domestic producers. The export rebate, on the other hand, is a rebate given to a producer by the producer’s home government when it exports goods. These export rebates are given to producers so that they are not at a competitive disadvantage in foreign markets.

The figure below gives an example, where we imagine the United States has a $40/ton price on carbon, the European Union a $50/ton price, and both implement BCAs on exports and imports:

Manufacturers and related stakeholders are often interested in export rebates as well as import charges. However, there are concerns that an export rebate could have a muddled net impact on emissions. On one hand, the strategy may decrease emissions by boosting cleaner production. On the other, it may increase emissions by making exported products cheaper where they are ultimately sold. Some critics say that there is no guarantee of reducing leakage if it is cheaper for producers to make goods in the high-emitting country and the government covers the heightened expense of international trade through export rebates. This potential pitfall—along with much larger WTO concerns about export subsidies—are reasons why some experts and advocates have been less focused on including export rebates in BCAs. Given the challenges of incorporating an export rebate, many proposals, historical and current, focus solely on import fees.

Benefits of a Border Carbon Adjustment

The primary benefit of a BCA is the idea that it “evens the playing field” of international trade and climate policy. A BCA would allow a nation to move forward with ambitious climate policies without the threat of competitiveness losses. That is, if nations feel more empowered to enact climate policy without the threat of competitiveness leakage, ambitious climate policies may become more politically palatable.

Experts have also noted the potential for significant reductions in emission leakage, and therefore global environmental benefits, relative to ambitious policies without BCAs (confirmed by various studies).

BCAs can also increase revenue for nations, since the foundational tenet of a BCA is that it places a fee on the emissions of imported goods. A European Union (EU) carbon border adjustment mechanism, which is set to go into effect in 2023, is estimated to raise between €5 billion and €14 billion (5.7 to 15.9 billion USD) in revenue each year. This revenue can be used to cover export rebates, invest in climate mitigation and resilience technologies, or distribute to citizens in the form of a dividend.

There is also the hope that BCAs could create an incentive for less ambitious countries to up their game and mitigate the use of this policy option.

Costs of a Border Carbon Adjustment

Perhaps the highest hurdles to implementing a BCA lie in the technicalities and the feasibility of the policy. If a BCA is large and encompasses many sources of carbon, the data and administrative demands grow too. Depending on the underlying mitigation policy at home and abroad—for example, various sectoral policies instead of one uniform policy—the BCA will likely need additional differentiations and additional data.

However, even where emissions data are available, decisionmakers also need to consider the robustness of the data. Asking questions about the data collection—for example, is it self-reported and is that reporting monitored—helps to better understand the limitations of these data. Importantly, the data are necessary for the foreign trade partners, not just the domestic firms. The US government has not left questions about foreign data unaddressed. Both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Department of Commerce evaluate foreign data and send investigators to foreign firms to do so. Presumably, this could be done in the case of BCAs (though perhaps at some expense).

This data question is likely more acute for developing countries, which may have fewer resources and systems in place to accurately calculate these figures. RFF research from October 2021 delves into question.

Looking past the technical hurdles facing BCAs, there are still some big-picture questions—perhaps the most critical is whether BCAs are an effective policy measure to address leakage and competitiveness concerns in a landscape of varied international climate policy ambition. BCAs could threaten diplomatic relationships and increase international tensions regarding both trade and climate. On the climate side, despite the potential benefit of encouraging ambition, BCAs could backfire and discourage it. On the trade side, there is the worry that implementing BCAs could open the door for potential retaliatory tariffs or even trade wars. This reflects how important policy design choices are when creating a country’s BCA. Decisions over what type and breadth of emissions to include, what industries to target, and which countries it applies to need to be answered. Additionally for successful policy implementation, these answers need to be defensible. Moreover, it may be important to think about BCAs in collaboration with other countries, not just as a unilateral policy.

Perhaps most importantly, BCAs would affect countries differently. Relatively developed nations targeted by a BCA, which have the funds and resources to invest in emerging clean energy technologies, will likely adapt. Poorer nations that do not have the same ability to implement emissions reductions policies may be at a disadvantage. With less ambitious climate policies, they may see their trade opportunities—and the economic development that goes with them—curtailed. This in turn could be detrimental to negotiations where countries are supposed to be working together to reduce global emissions. Or it might suggest that a more nuanced approach to the application of BCAs to poorer countries is needed.

The World Trade Organization’s Role

In designing a BCA, countries can consider the role of the World Trade Organization (WTO), a global organization that oversees and regulates trade between most nations. The WTO ensures that member organizations have fair access to international markets; for example, if the United States wants to export televisions to South Africa, the WTO mandates that South Africa give the United States the same access to its markets as it gives to its domestic producers.

There are three pathways that have been suggested regarding the challenges of WTO regulation:

- Attempting to fully comply

- Proposing an exemption

- Arguing that lack of foreign climate regulation is an actionable subsidy

Among the criteria to comply with the WTO, a BCA must have objective methodology, the import charge cannot exceed charges on a similar domestic product, and an export rebate cannot exceed the domestic tax paid on the product. Additionally, importing nations cannot credit foreign companies that face more stringent regulations than others. Ultimately, the WTO requires that countries not unjustifiably discriminate against goods from other countries in favor of domestic producers, or favor imports from certain member countries over others. These rules and regulations can make it difficult to create a BCA that is WTO compliant, especially for BCAs that function under a partial carbon price or non-price system.

RFF scholars Brian Flannery and Jan Mares, in collaboration with WTO experts Jennifer Hillman and Matthew Porterfield, have proposed a framework for WTO-compliant border adjustments that rely on already-approved WTO regulatory mechanisms. In two 2020 reports, they describe how border adjustments set up around a greenhouse gas tax and an appropriately designed greenhouse gas index (noted above), can be framed in a fashion analogous to value added taxes (VAT) that are allowed under WTO rules.

For an exemption to be possible, WTO’s Article XX affirms that a BCA would have to focus on environmental effects like emissions leakage and not be seen as a trade barrier. RFF Senior Fellow Carolyn Fischer and Susan Droege of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs write that BCAs must consider that some nations have different compliance mechanisms or methods of reducing emissions that may not be covered by the border adjustment, which could be remedied with exemptions or more robust policy design. They suggest the exemption of countries that:

- Implement a national emissions cap

- Take “adequate” national actions other than a national cap

- Implement a sectoral cap

- Is considered a least developed or low-income country

- Require administrative flexibility due to the risk of double charging, etc.

Joseph Aldy, on the other hand, proposes a “countervailing duty” on targeted groups that imposes a tax based on the notion that the absence of adequate foreign climate regulation amounts to a foreign production subsidy. This amounts to an actionable subsidy that can be subjected to a countervailing duty. Whether this would survive a WTO challenge is unclear—but it is also unclear when such a case would be taken up given member disagreements over settlement procedure.

In a similar way, a country could simply pursue a BCA without regard to WTO consequences. While there might be consequences to this, they may be far down the road. Moreover, this may lead to a more serious reckoning of trade rules given the reality of climate change—particularly if the BCAs were pursued in partnership with several like-minded countries enacting ambitious climate policies. Approaches that are increasingly outside the WTO’s jurisdiction also run the risk of creating international trade disruptions and/or upset within global climate negotiations.

Concluding Thoughts

Border Carbon Adjustments: Not Theoretical for Long

In July 2021, the European Commission proposed a BCA which would put a carbon price on imports of a select group of products to avoid leakage and support domestic industry. The policy is designed with the WTO and EU structures in mind. Importers to the EU will buy carbon certificates corresponding to the carbon price they would have paid if they were manufactured in the EU. If they can prove that they have already paid a carbon price in their domestic country, that value will be subtracted from the cost of the fee.

As the first BCA that might be implemented on the global stage, the EU policy would be gradually phased in, and would start by applying only to a select few carbon-intensive goods like iron and steel, cement, fertilizers, aluminum, and electricity generation. As a part of this phase-in, importers would have to report emissions embedded in their products without paying a fee until 2023 with the intention of making the roll out smooth for industries which are not accustomed to such reporting requirements. The program should be fully operational by 2026.

BCAs, which are now shifting from the theoretical to the practical, require thoughtful policy design to account for the policy option’s significant costs and benefits to global trade. More research can help us understand the effects of import fees and export rebates on emissions, the economy, and equity. This is true both as BCAs are contemplated and after they are implemented. BCAs are likely to be an ongoing and growing policy issue globally for the foreseeable future.

Additional RFF Resources

Common Resources posts:

- Border Carbon Adjustments: How to Implement in Countries That Don’t Have a Carbon Price

- Implementing a Framework for Border Tax Adjustments in US Greenhouse Gas Tax Legislation and Regulations

- Designing Border Carbon Adjustments When Carbon Is Not Explicitly Priced

- Accounting for Emissions in Global Trade with a Greenhouse Gas Index

- A Solution to the Competitiveness Risks of Climate Policy: Countervailing Duty Law

Resources Radio podcasts:

- Border Tax Adjustments, with Brian Flannery

- Carbon Pricing Proposals in Today's Congress, with Marc Hafstead

Research:

- Border Carbon Adjustments without Full (or Any) Carbon Pricing

- Framework Proposal for a US Upstream GHG Tax with WTO-Compliant Border Adjustments: 2020 Update

- Policy Guidance for US GHG Tax Legislation and Regulation: Border Tax Adjustments for Products of Energy-Intensive, Trade-Exposed and Other Industries

- Developing Guidance for Implementing Border Carbon Adjustments: Lessons, Cautions, and Research Needs from the Literature

- Addressing the Leakage and Competitiveness Risks of Climate Policy