Resource Inadequacy: Why a Crucial Component of Keeping the Lights on Is Getting Harder

This issue brief offers a primer for policymakers considering reforms to ensure sufficient power supply, enhancing grid reliability.

Electric power is an essential resource for households, businesses, and economies, from keeping lights and life support machines on to powering water conveyance and transportation networks. When there is not enough electricity, the resulting outages can be expensive and even deadly, impacting business activity, comfort, and health.

One prime example is the electricity shortage event that occurred in Texas in February 2021. Winter storm Uri caused 246 deaths according to official counts (DSHS 2021), primarily due to power outages, with one estimate putting the death toll over 800 (Weber and Buchele 2022; FERC/NERC 2023). The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas estimated the total economic cost of the outages at $4.3 billion (Golding et al. 2021).

Power outages resulting from extreme events, like the ones in Texas, are becoming more frequent and severe. The traditional methods for ensuring sufficient power supply and incentivizing new investment were not designed for the range of innovation in electric resources that has emerged or the speed of projected demand growth. In addition, it now takes longer to site, build, and interconnect new resources to the power grid. Beyond threatening reliability, current practices can exacerbate affordability concerns and slow decarbonization.

This issue brief offers a primer for policymakers considering reforms to ensure sufficient power supply (“resource adequacy”). While resource adequacy is only one dimension of electric reliability, we focus on it because the complex economic fundamentals that have driven existing resource adequacy market designs are not always fully appreciated.

1. What is resource adequacy, and how does it relate to electric reliability?

Avoiding power outages and ensuring households and businesses have access to sufficient electricity (“electricity reliability”) has several critical components, such as:

- Resource adequacy refers to ensuring that the power system has enough supply to meet demand at all times and avoid an electricity shortage. Resource adequacy is affected by the amount of electricity demanded, the availability and capabilities of electricity “resources” (e.g., generators, storage) and the available transmission capacity to deliver power from other regions.

- Operational reliability refers to how the grid is managed. This includes continuous monitoring and adjustment to ensure that electricity supply and demand are balanced. Even small deviations in this balance can cause outages.

- Delivery infrastructure reliability refers to physical threats to the transmission and distribution grid that brings power to households and businesses. There are millions of miles of power lines exposed to wind, trees, and other hazards that, if compromised, can cut access to power.

While all three components of reliability are important, this issue brief focuses on resource adequacy because it is a particularly complex economic and policy challenge, especially in areas with competitive markets.

2. What is the government’s role in resource adequacy?

Whether we need forward-looking investment in resource adequacy and whether the government needs to intervene to ensure resource adequacy are highly debated topics among experts. While most of the organized electricity markets in the United States include some forward-looking regulatory intervention to ensure resource adequacy, such as centralized investment planning or forward incentive payments, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), for the most part, does not. Instead, ERCOT operates what is called an “energy-only market.” We break the economic case for forward-looking regulatory intervention into the following four components.

2.1. The Energy-Only Vision

For many goods and services, the good or service itself is the only product. Consider the market for toilet paper. There are toilet paper producers, and there are consumers who want to buy toilet paper. A consumer who buys toilet paper typically does not also buy the assurance that there will be toilet paper available to buy in the future. Instead, if demand is high, prices should increase and attract new toilet paper producers into the market. This approach is the energy-only market vision: Electricity “buyers” (e.g., electric utilities, large industrial customers, or other entities that supply electricity to consumers) purchase electricity from “sellers” (e.g., generators) as they need it without any long-term availability guarantees, and high prices attract new electricity supply resources when needed. This explanation abstracts from products related to ensuring real-time supply and demand balancing and meeting other operational reliability requirements.

2.2. Electricity Has Challenging Physical Properties

To understand the shortcomings of an energy-only market, it may help to first understand two challenging physical features of electricity.

- Electricity is expensive to store (even though storage costs have been decreasing). While toilet paper suppliers can stock extra product in a warehouse to withstand a demand shock or to smooth demand seasonality while maintaining steady production, grid operators need to constantly balance instantaneous electricity supply and demand to avoid outages.

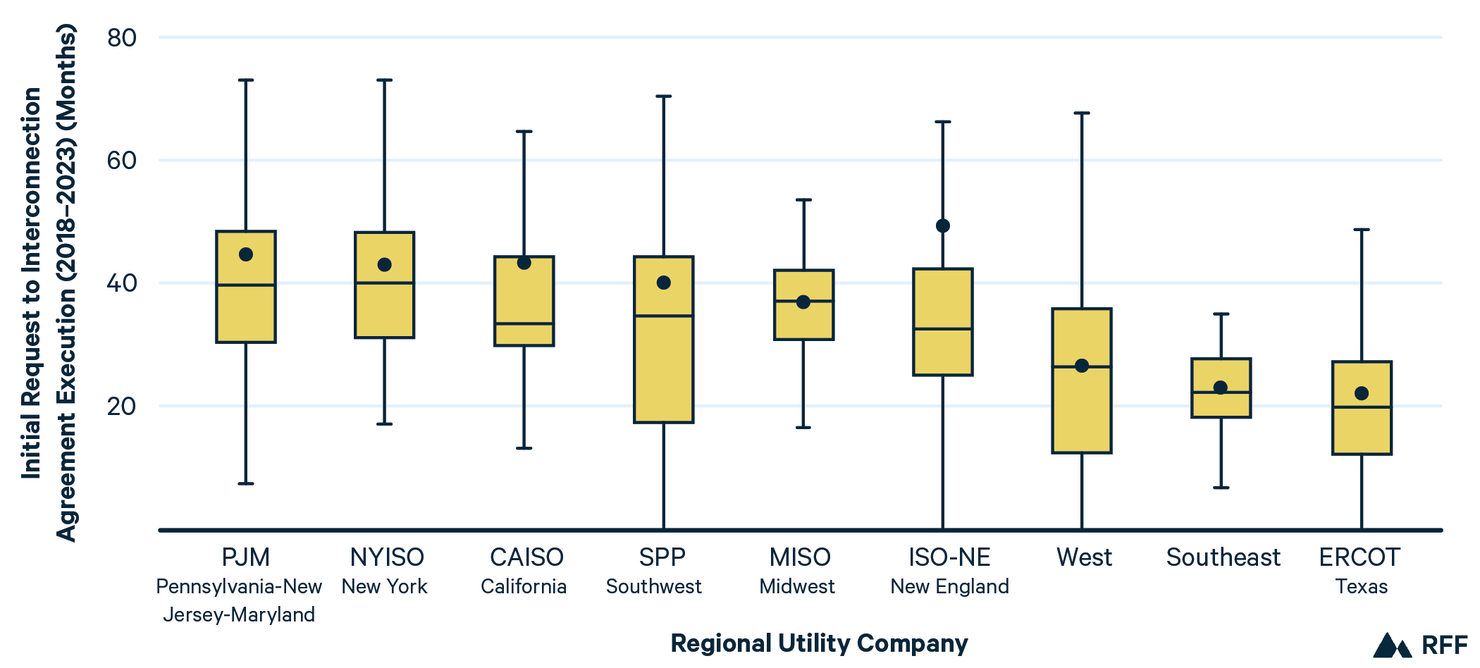

- It takes a long time to site, build, and interconnect new electric generators. Construction alone takes two years for renewable generators, four years for thermal generators, and five years for nuclear generators, on average (IEA 2019; Thurner et al. 2014), and many timelines are getting longer due to supply chain issues (Anderson 2025). Acquiring necessary state and federal permits to build and receiving grid operator approval to connect to the grid (“interconnect”) can take years. In 2023, the median time between when a generator first requested to interconnect and when there was an executed interconnection agreement was over two years (Rand et al. 2024), with substantial variation across regions (see Figure 1). As a result, there is a limit on how much electricity can be produced in the near-term (a “capacity constraint”).

Figure 1. Duration of Interconnection Process by Region (2018–2023)

Source: Rand et al. 2024.

2.3. Why Explicit Investment in Resource Adequacy is Desirable

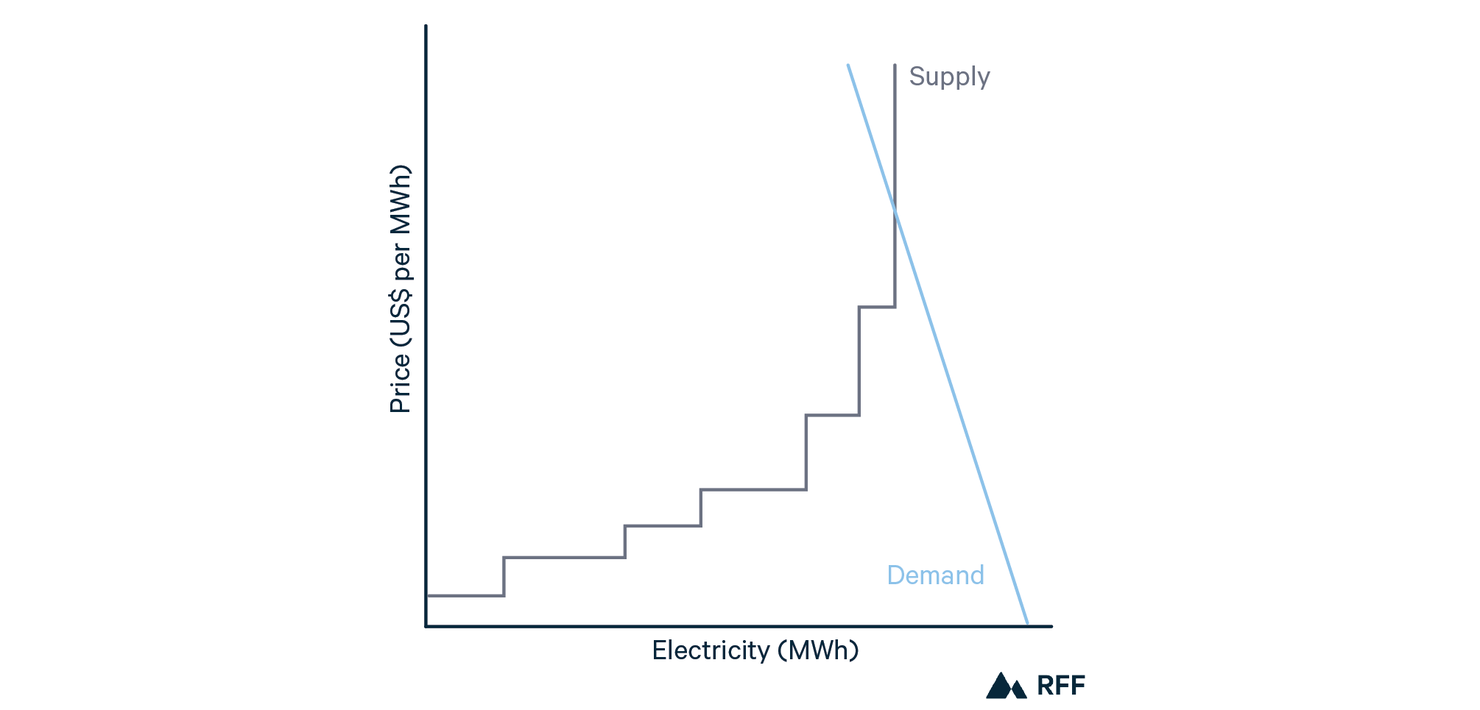

Even with capacity constraints, shortages should not occur in a well-functioning market. Instead, as illustrated in Figure 2, high demand would simply lead to an especially high price, and only buyers willing to pay that price would get electricity. Over time, high prices may attract more producers to enter the market, and buyers looking to reduce cost uncertainty could also hedge high prices through long-term contracting with individual producers or trading in financial markets.

Figure 2. Illustrative Supply and Demand in an Energy-Only Market with No Distortions

However, there are imperfections and regulations in electricity markets (“distortions”) that interact adversely with physical features:

- Many electricity consumers, such as households and businesses, purchase electricity from a reseller, such as a utility, and pay retail prices that deviate from wholesale prices (“imperfect pass-through”). For example, regulators often prefer retail rates that are more stable than wholesale prices, which can vary within an hour, and limit the price risk and uncertainty borne by consumers (Bonbright 1961).

- Many retail consumers do not fully pay attention to the prices they pay (Ito 2014; Kahn-Lang 2023).

- Price caps in wholesale electricity markets are common. While some economists blame price caps for the existence of resource adequacy issues, the other market distortions presented here could cause resource inadequacy even without price caps.

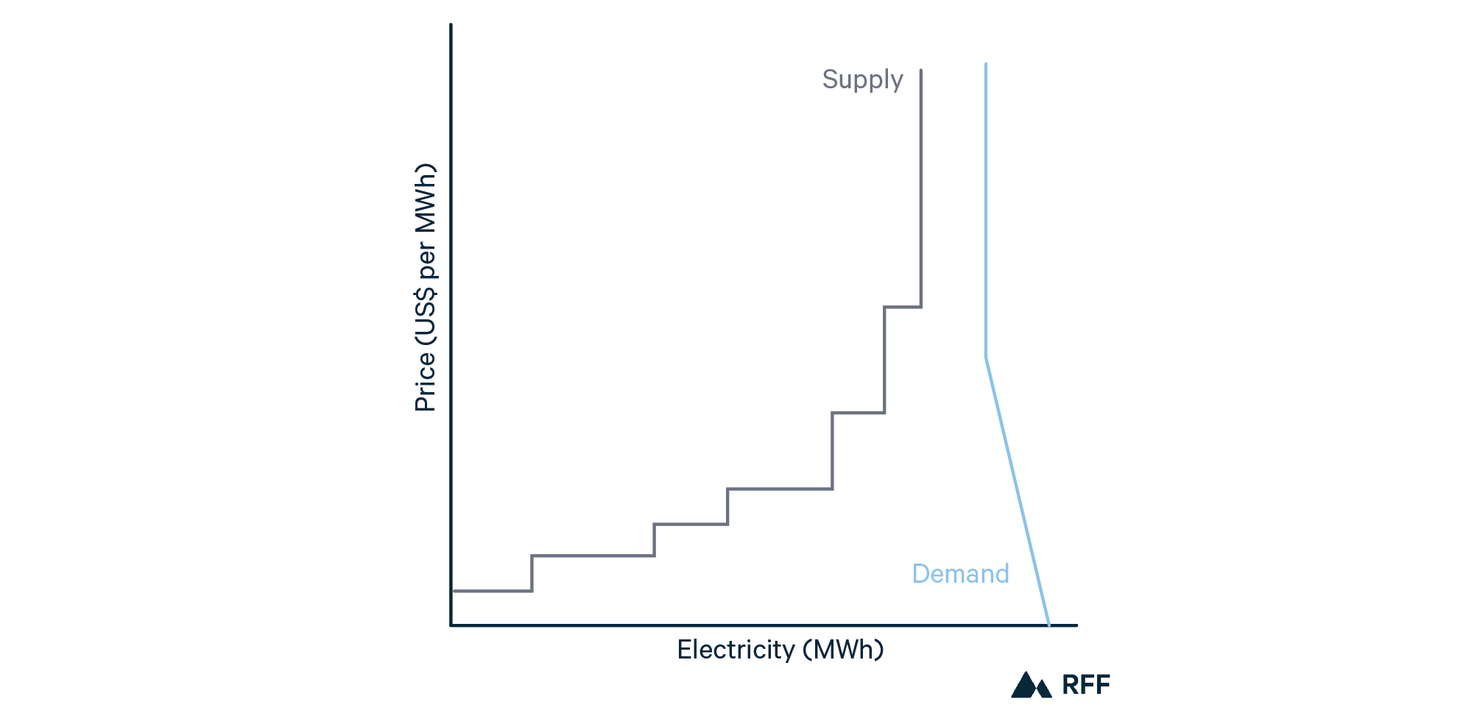

These factors affect how responsive electricity usage is to prices and can lead to shortages. If you went to buy toilet paper and found that the price was $9,000 per roll, you might choose not to buy any. In contrast, when electricity was $9,000/MWh in Texas in February 2021, many people who would not choose to pay that much still used electricity, some later receiving bills for thousands of dollars (McDonnell Nieto del Rio; Bogel-Burroughs and Penn 2021), and many facing much lower prices. This example illustrates how inattention and imperfect pass-through of retail prices to consumers mean higher wholesale market prices may not always reduce the electricity demanded. As depicted in Figure 3, this lack of responsiveness can lead to electricity shortages where electricity demand exceeds supply at any price.

One issue with an energy-only market design under a risk of shortage is that there is uncertainty about future weather and market conditions and, therefore, uncertainty about future shortages. Consumers may be risk averse and would pay a lot to avoid blackouts during an especially cold year, but sellers may not be symmetrically risk seeking. Consider a developer deciding whether to build a generator that would only be profitable in an unusually cold year when other generators are unavailable. The developer may not build the generator with little certainty over profitability, even though it would be valuable for buyers to have electricity in a cold snap.

Price caps can further reduce incentives to build—or not retire—by limiting profits during extreme conditions.

With this incentive misalignment, it may be socially desirable for buyers to pay resources for the option to purchase electricity in the future: They may want to explicitly invest in resource adequacy beyond an energy-only market structure.

Figure 3. Illustrative Supply and Demand in an Energy-only Market with Partially Inelastic Demand

2.4. The Need for Government Intervention or Regulatory Requirements

Given that inattention and imperfect pass-through of wholesale prices to consumers are likely unavoidable, a market for the option to buy electricity in the future might be the next-best solution for ensuring resource adequacy. The question then becomes: Is government intervention necessary, or would buyers procure enough resource adequacy on their own?

Unfortunately, resource adequacy is nonexcludable, meaning that a utility or other buyer that invests in resource adequacy cannot prevent others from benefiting from the investment. If another household stockpiles toilet paper, it does not prevent you from running out. If another buyer procures electric resource adequacy, they cannot exclude you from the benefit of fewer blackouts. Consequently, in the absence of regulatory or government intervention, buyers have incentives to lean on others’ resource adequacy investments, resulting in too little total investment in resource adequacy.

3. Traditional Resource Adequacy Solutions

The solution to resource adequacy issues is typically for a regulator or a sanctioned independent third-party agency to determine the resource adequacy need and require certain entities to pay to meet this need. The exact approach varies regionally.

3.1. Resource Adequacy Needs Determination

The first step is setting a resource adequacy goal. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) sets suggested standards for assessing resource adequacy (NERC n.d.). These include the “1 in 10” standard: The system should have sufficient electricity supply such that outages from electricity shortages would only be expected to occur once in ten years. Most US jurisdictions use a version of this standard to determine whether they are resource adequate.

3.2. Creating a Plan and Allocating Responsibilities

How to meet these resource adequacy standards and assign responsibilities to individual buyers is up to the discretion of state regulators and utilities. Common approaches include:

- An investor-owned utility that owns its own electric generation is subject to utility regulation. A regulator may scrutinize and approve an individual utility’s plans for meeting the resource adequacy goals and recovering the associated costs from consumers. For example, when assessing an investment plan, the regulator may consider the reasonableness of the utility’s demand forecast, the cost of new resource adequacy investment, and, importantly, the benefits of such investments across customers of multiple neighboring utilities in the regulator’s jurisdiction. While there could be uncaptured benefits outside of the regulator’s jurisdiction, these may be small or zero if there is a credible commitment to preventing in-jurisdiction shortages from adversely affecting neighboring jurisdictions.

- Under traditional centralized planning, the regulator or a sanctioned, independent third party leads the planning. They develop a plan to meet the reliability target and allocate the associated responsibilities to buyers. These responsibilities may be highly prescriptive or more flexible. A municipal utility may also conduct planning of this nature and assume all responsibilities itself.

- In areas where resources compete to sell electricity, a capacity market can parallel centralized planning but use market mechanisms to develop the resource adequacy plan. The regulator or third-party organization holds auctions to solicit commitments from resource owners to be available when needed and to reveal their costs of doing so. The goal is to procure the least-cost portfolio of resources to meet the reliability needs on behalf of electricity buyers, pay these resources enough to stay in—or enter—the market, and assign the costs to buyers.

Market and nonmarket approaches can achieve the same reliability, but the costs may differ. In all approaches, planners make assumptions or elicit information about resources’ availability and costs to determine the resource portfolio. Well-designed market approaches are more likely to achieve the cheapest portfolio to society as a whole. However, there are also differences in the distribution of costs, benefits, and risks across consumers and resources. Which of these approaches ultimately leads to lower consumer costs depends on market conditions.

Across all three approaches, estimating resource availability was initially relatively straightforward. Planners assumed generator outages were independent of other generators’ outages, their own outage history, and weather (Lauby 2022).

4. The Traditional Paradigms Are Being Challenged

While traditional methods may have been sufficient to ensure resource adequacy for the grid of the past, extreme weather events and decarbonization bring new challenges for identifying resource adequacy needs and the optimal portfolio of resources to meet those needs.

At the same time, with rapid demand growth, policymakers and industry experts are increasingly concerned about the ability of traditional resource adequacy approaches to attract enough resources in a short time frame regardless of costs. Entry barriers undermine thoughtful resource adequacy reform and can act as political barriers to stable investment signals in capacity markets.

4.1. Identifying Long-Term Resource Adequacy Needs and Solutions

Climate change’s effects, renewables, and decarbonization policies present three new challenges to the traditional resource adequacy paradigms.

First, they make meeting standard reliability targets more expensive. We see more occurrences of unprecedented demand and weather events that cause multiple, concurrent generator outages. At the same time, many renewable resources have less predictable generation than traditional resources, further increasing uncertainty about supply. Some decarbonization policies, such as renewable portfolio standards, prescribe what resources can be on the system and how fast they must come online, which can further increase costs in the near term.

With higher investment costs, there may be value in revisiting the 1-in-10 reliability standard and thinking deeply about the costs of outages, how they vary with outage characteristics and weather, how they compare to the investment costs, and how to reduce them and make outages less deadly. Economists have attempted to quantify these outage costs, defined as the “value of lost load” or VOLL. The VOLL depends on the location, timing, and duration of the outage in question, and different analytical methods result in highly variable estimates of the VOLL (Gorman 2022).

Second, new technologies are challenging assessments of resource adequacy and resources’ contributions to resource adequacy. Wind, solar, and natural gas each rely on a shared energy supply source, resulting in correlated resource availability. Therefore, the most constrained times with the highest risk of undersupply are no longer necessarily the hottest or coldest days of the year but instead may be driven by correlated outages. In addition, with increased interest in storage and demand response, the duration of the resource adequacy events increasingly affects availability. System planners have turned to new resource accreditation methods to better compensate resources for their resource adequacy contributions, but these solutions are still the subject of robust debate.

Finally, as the current resource adequacy constructs are being challenged, electric resources are also relying more on resource adequacy payments. With more renewables with zero fuel costs, wholesale electricity market prices have decreased and have a higher variance (Seel et al. 2018). Investors and resources may, therefore, require more revenue from other sources, such as resource adequacy payments.

4.2. Incentivizing Investment in the Needed Time Frame

Resource adequacy payments aim to attract development of new resources, but experts are concerned about any approach being able to attract rapid new development. Demand is growing at speeds unprecedented in recent history, and barriers to siting, permitting, building, and interconnecting to the power grid are high.

Resource adequacy payments are also often not sufficiently long term to incentivize new generator development. For example, capacity markets typically only provide guaranteed revenue for one year, whereas most financers of new generators typically require longer-term revenue guarantees. To attract additional new investment, capacity prices would likely need to be consistently and predictably high for a sustained period.

However, consumers and policymakers have been shaken by sudden increases in capacity auction prices in the Pennsylvania–New Jersey–Maryland Interconnection (PJM) region. In response to demand growth and resource accreditation changes, total capacity costs increased from $2.2 billion for the 2024–2025 delivery year to $14.7 billion for the 2025–2026 delivery year. Ultimately, the price increases have led many states to pressure PJM for market changes to lower prices, and some states are considering adopting new state-level resource adequacy strategies that would lower their exposure to the capacity market prices.

As electricity affordability becomes a political focus, solutions for reliability may face significant scrutiny over real or perceived costs they place on consumers. The response to high capacity prices in PJM also illustrates the challenge in relying on capacity markets as an investment signal: Regulators often respond to high prices with market changes, thereby undermining the price signal itself.

At the same time, the PJM example calls into question the merits of capacity markets when they are ineffective at attracting new entry in the short term. It often takes longer to site, build, and interconnect new resources than the time frame between a capacity auction and when the resource needs to be available to deliver power. With the dramatic rise in electricity demand from data centers, price signals in PJM have changed quickly, and developers have not had enough time to respond by building and interconnecting new resources. The resulting windfall for existing sellers—and the price tag for existing consumers—has challenged policymakers to reconsider the capabilities and limitations of the current capacity market construct.

5. Economic Fundamentals Can Ground Policy Debates

The devastating electricity shortages in Texas in 2021 and the high capacity prices in PJM may be harbingers of future challenges. The industry is exploring incremental and radical reforms to improve modern resource adequacy practices. Lo Prete et al. (2024) describe many proposals for radical changes and offer a framework for comparing if and how they address the key challenges.

As the industry debates solutions, the economic fundamentals and the challenges to the traditional paradigms discussed here can illuminate tradeoffs and limitations. For example, reducing the period between when resource adequacy payments are provided and when the electricity is needed may lower costs, but it does not solve the fundamental issue of underinvestment in resource adequacy and insufficient incentives for the development of new supply resources. Increased state-level long-term contracting may reduce uncertainty in costs to consumers, but it does not address the uncertainty about supply availability during unprecedented extreme weather events or the fact that meeting existing reliability standards is becoming more expensive. Moreover, none of these approaches can solve the near-term reliability issues associated with rapid electricity demand growth if demand remains largely inflexible and new supply resources cannot build and interconnect to the grid in a timely manner.

It is important to consider all these challenges and the desired objectives when considering the suite of solutions. Improved understanding of how extreme weather events, demand growth, and resource availability affect our resource adequacy needs is essential in any reform approach. Understanding and appreciating the economic issues underlying electricity markets can help decisionmakers evaluate the landscape of possible solutions.