The Strategic Game of Rare Earths: Why China May Only Be in Favor of Temporary Export Restrictions

This brief explores the implications of China’s export controls on rare earth elements and future policymaking through the lens of game theory.

1. Introduction

In April 2025, China imposed export controls on seven rare earth elements (REEs) and related embedded products to all countries (Jackson et al. 2025), intensifying an already critical debate over the security and resilience of global supply chains. The Chinese announced that exporters must apply for licenses to sell these materials overseas, a move widely seen as a strategic maneuver. The restriction, though not an outright ban, introduces review mechanisms that complicate export logistics and international procurement. The elements subject to the restrictions include scandium, yttrium, samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, and lutetium. These materials are classified as medium and heavy rare earths, known for their magnetic, optical, and catalytic properties. Each plays a specific and often irreplaceable role in a range of high-tech and strategic sectors.

These restrictions came at a time when trade tensions were escalating between the United States and China and sent ripple effects through industries that rely on rare earths for advanced manufacturing, defense, clean energy, and digital infrastructure. In June 2025, a framework for a trade deal was agreed upon between the United States and China, which was expected to ease export restrictions of rare earth products (Miao and Feng 2025). Despite the trade deal, it is important to note that the licensing system to obtain approvals from China still holds good for rare earth and related product exports. Though it is too early to state the effects of the trade deal on exports of rare earth products for all sectors, it is being reported that exports to the United States surged in June 2025 compared to May (Reuters 2025), though approvals for western companies are taking longer and there is increased scrutiny (Emont et al. 2025).

China dominates the entire rare earths value chain. With China mining over 60 percent and processing over 80 percent of the world’s rare earths (REIA, 2025; Baskaran, 2024), and producing around 90 percent of the world’s high-performance rare earth magnets (Bradsher 2025), significant global dependence on a single country for these materials creates both economic vulnerabilities and strategic concerns. This article explores the implications of the current restrictions, the industrial relevance of the targeted elements, and how the situation can be understood through the lens of game theory. Specifically, our lens on this issue provides an understanding of why China reversed course in terms of restricting exports of rare earth products.

2. Industrial and Strategic Applications

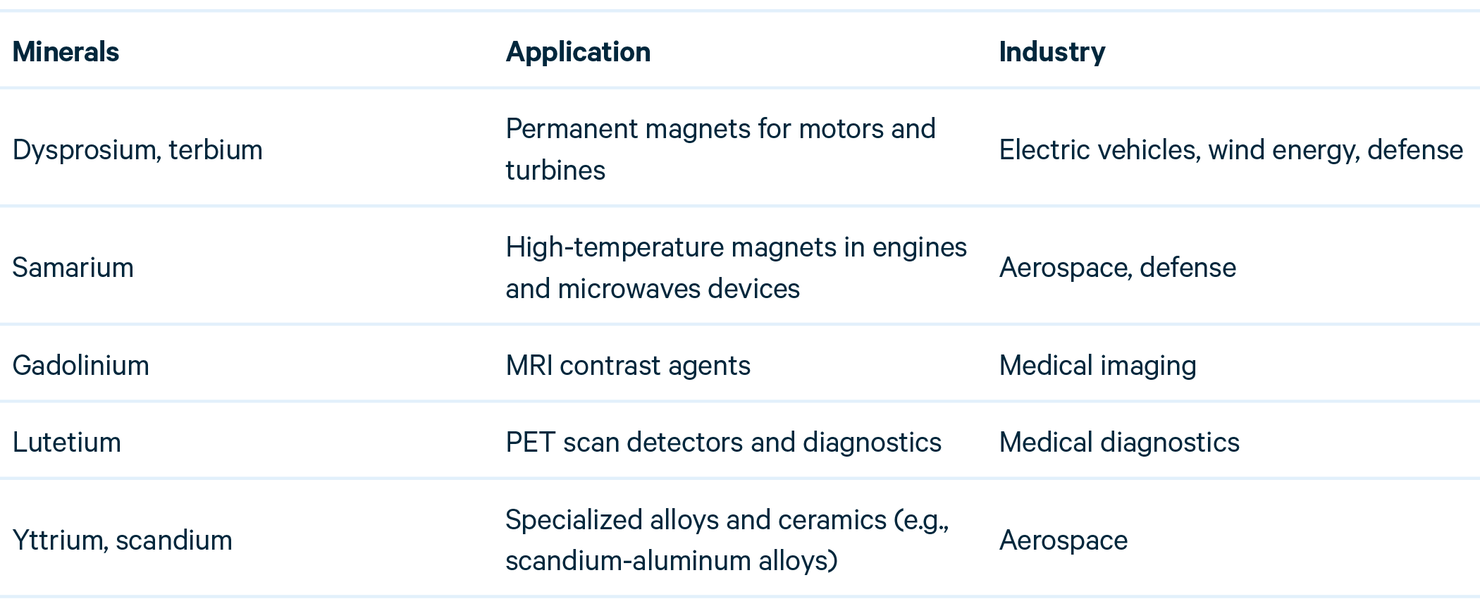

The applications of the restricted REEs span several mission-critical domains, as described in Table 1. These applications are integral to both economic competitiveness and national security, as emphasized in the International Energy Agency’s 2024 Critical Minerals Market Review (IEA 2024).

Table 1. Key Rare Earth Elements and Their Industrial Applications

Note: Table created by the authors based on information from Van Gosen et al. (2014), Balaram (2019) and Nguemgaing (2025).

3. Rare Earths: A Game Theory Analysis

The implications of China’s export policy can be analyzed through a game theoretic lens, offering insight into potential outcomes based on different strategic choices. In our approach, we model a two-player game between China and rest of the world (ROW). In the current setting, China controls processed REEs and the downstream REE products market, while the ROW depends upon Chinese outputs given a broad lack of capacity for REE refining and lack of a downstream REE value chain.

Consider the following strategic options for the two players:

- China can either restrict or continue to export REEs and rare earth products

- The ROW can maintain status quo, or invest in the REE supply chain

3.1. One-period outcome 1: China restricts exports, leading to ROW investment

If China restricts exports and the ROW invests in sufficient capacity to fill the gap, this allows the ROW to reduce its dependence on China, which harms China by reducing its long-term dominance. Under this outcome, the ROW would continue to face supply chain restrictions for REEs during the phase of capacity buildup. There would be a risk of excess global capacity if China lifts its restrictions. Overall, restricting exports would incur significant investment costs on the ROW, and harm China’s interest in controlling the market. Whether or not these export restrictions are temporary, they will affect the dynamics of this outcome, particularly in a repeated game; we discuss this further in Section 4.

3.2. One-period outcome 2: China restricts exports, ROW maintains dependence on China

If China restricts exports and the ROW waits, price of rare earths will go up, while Chinese export quantities will shrink. However, the rise in prices due to the imposition of export restrictions would contribute to an increase in China’s sales revenue, under the assumption that ROW demands for rare earths are price-inelastic. The increase in China’s international revenue would depend on the level of the export restriction and the inelasticity of demand. China may gain short-term leverage by creating increased pressure to the ROW to come to the negotiating table, while the ROW will face damaging impacts from costlier REE supplies.

3.3. One-period outcome 3: China continues exports and ROW invests

If China continues exports but the ROW still invests to diversify geographic supply, the outcome will depend on the cost-competitiveness of the ROW.

If the ROW’s prices for REE products are competitive with China’s prices, China will lose its market-share dominance while the ROW builds resilience. REE capacity utilization in China would fall, though the risk of overcapacity depends on the size of the ROW capacity expansion. In practice, the ROW does not have to replace Chinese capacity but invest only enough to offer competitive alternatives.

However, if the new supply brought online by the ROW fails to be price-competitive with the Chinese supply, then it will fail to draw demand away from China unless ROW governments provide indefinite support through direct subsidies or tariffs on Chinese products and cost increases passed on to consumers in the ROW.

Under this scenario, the ability for the ROW to invest will depend on the willingness and capability of nation states to (possibly indefinitely) subsidize their domestic industry.

3.4. One-period outcome 4: Maintenance of status quo

If both sides maintain the status quo (China continues exports and the ROW does not invest), the ROW remains dependent while short-term stability is preserved. With increasing demand, the dependence on China for the ROW would keep increasing.

3.5. Putting it all together

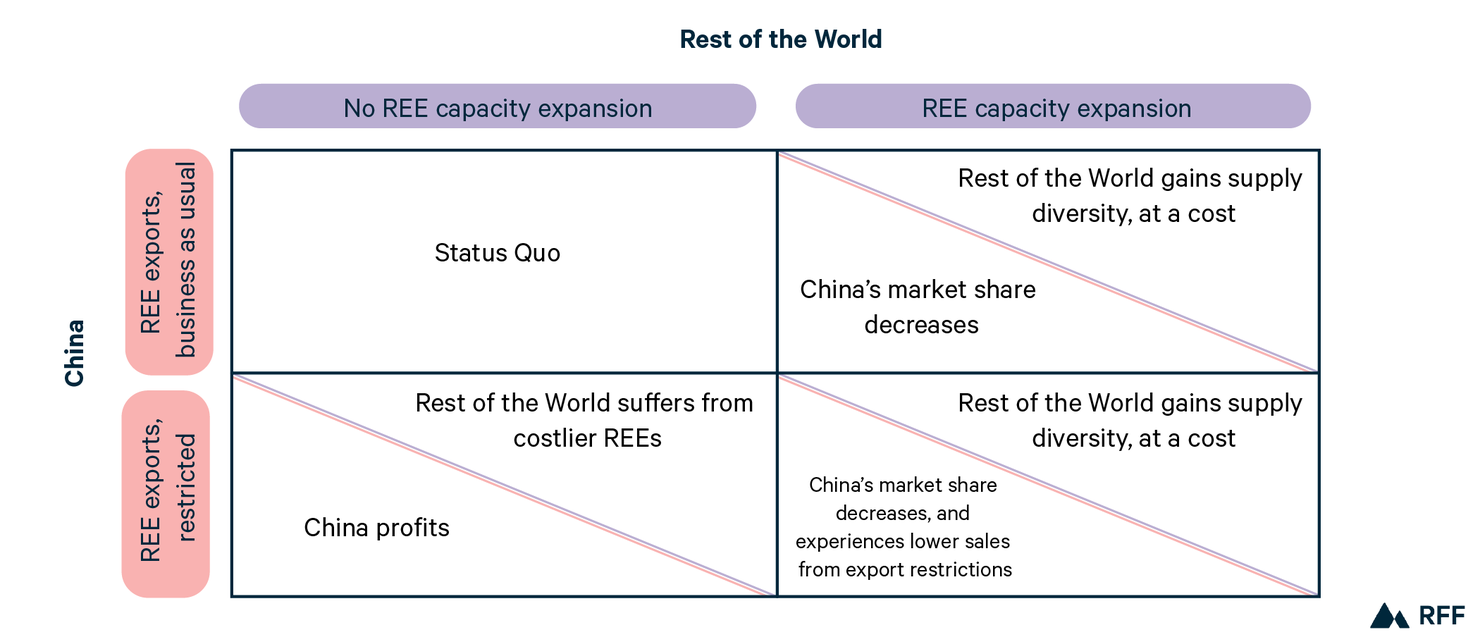

Figure 1 below shows in matrix form the various single-period outcomes. As can be seen here, the only stable equilibrium for a single-period game is status quo, as any deviation would be worse for both China and the ROW. For example, if the ROW decides to expand capacity in a scenario where China does not restrict REE exports, the ROW incurs significant cost in investment. Though it gains supply diversity, it does not improve its ability to access low-cost REEs. Because this is a one-shot game and there is no future risk of export bans, this action would incur costs on the ROW and would also harm China by reducing its market share. Alternatively, if China decides to restrict REE exports, the best outcome for the ROW is to expand capacity to ensure it has access to the REEs it needs; however, this would harm China even further, as now those restricted exports could not be priced higher (due to the ROW having alternative options for access).

Figure 1. Strategy and Payoff Matrix for the REE Supply Game Between China and ROW

However, in a repeated game, the outcome can be quite different. Moving away from the status quo can trigger a change in the equilibrium. If China restricts exports for a period and then relents, the risk associated with possible repeat restrictions could lead to additional ROW investment to temper China’s market power. This outcome is consistent with the dynamics described by the Folk Theorem in repeated games, which shows that long-term expectations and the threat of future retaliation or cooperation can sustain behaviors like restraint or deterrence that would not be viable in a one-shot game (Fudenberg and Maskin 1986).

We discuss this in more detail in the next section.

4. Exploring Timing of Export Restrictions

In a repeat game, the resulting outcomes could change depending on the timing of China’s decisions to restrict exports—specifically, whether these export restrictions are temporary or sustained. We explore each of these possibilities below.

4.1. Scenario One: Chinese Export Restrictions Are Relatively Substantial and Long, and the Damages Cause the ROW to Build Capacity

In this scenario, the export restrictions on REEs from China are relatively long (e.g., several years). In this setting, the most likely outcome is that the ROW will invest in capacity, as described above, because a sustained REE export restriction will cause prices for restricted materials to spike and remain high, given limits on the capacity of the ROW to substitute away from the restricted REEs. Such a scenario would harm industries that rely on these inputs, particularly in the short run prior to ROW capacity being built up.

The damages will speed up ROW efforts to invest in rare earths extraction and processing capacity to replace lost Chinese output. The acceleration of REE extraction and processing outside China would lead to undercutting China’s dominance due to geographic diversification. However, this assumes that the new ROW capacity can be operated at marginal costs that are less than the elevated REE prices. (In practice, high prices also will create incentives for advances in recycling and substitution in the ROW.) There also is a risk of overshooting, a well-known pattern in mineral economics, where high prices lead to new investment, only to trigger future price declines that threaten the viability of those same investments (Tilton and Guzman 2016; Tilton et al. 2018). It is important to note, however, that both end-of-life recycling and complete substitution away from REE magnets face significant challenges.

If China does back off on its supply restrictions once its market dominance is weakened, then prices will fall—even below their prerestriction levels—with the new ROW capacity online. At lower prices, the new ROW capacity may not be able to cover its costs in the absence of policy support. This possibility needs to be included by ROW decisionmakers when they contemplate challenging China’s market dominance. The presumption when ROW capacity is expanded is that the expected benefit of lessening price run-ups exceeds the cost of policy support for the new capacity, times the probability it would be needed.

If the United States decided to heavily invest in REE extraction, processing and magnet creation, this could feed into broader US policy goals around industrial development and supply chain resilience. However, the cost of doing so could be quite high. For example, in July 2025, the Department of Defense (DoD) invested $400 million in a rare earth magnet producer, MP Materials (MP Materials 2025), to create a domestic supply chain of magnets for use by the DoD. To ensure that the company would succeed financially, the government provided off-take agreements for 10 years at a price floor of $110/kg—about $50/kg higher than its spot price (Zeitlin 2025). Thus, though the DoD ensures its supply of magnets for the next decade, it comes at a high financial cost to the country (and the creation of a value chain that may not be internationally competitive).

From a strategic perspective, the longer-term loser in this scenario would be China. Its investments in downstream REE processing infrastructure, estimated to be worth billions, would face underutilization due to smaller export markets. As its market leverage diminishes over the longer term, the decision to halt exports becomes economically irrational. This outcome corresponds to a classic game-theoretic scenario in which the short-term gain of exerting control is outweighed by long-term strategic losses.

These observations suggest that this scenario is relatively unlikely to occur, as exemplified by the rapid reversal of China’s 2025 REE export restriction policy.

4.2. Scenario Two: Export Restrictions are More Modest, Temporary

In this scenario, the export restrictions on the REE value chain from China are mild and short-term. The dynamics of this scenario could play out as follows.

China imposes export restrictions. These restrictions not only lead to an increase in prices for REEs; they also limit the amount of REEs available for end-product manufacturing (e.g., electric vehicles, defense equipment) around the world. Manufacturers who do not have enough inventory and are unable to substitute away from REEs are affected the most. Damage felt by the ROW such as production delays pushes the ROW to begin investing in substitution measures and working on strategies to set up capacity for REEs. While the ROW is in the process of doing so, however, China withdraws the export restrictions. As prices fall, efforts taken by the ROW either come to a halt as there is no incentive to continue investments, or they might continue at a slower pace leading to some small level of diversification in the ROW. The result is that China continues to be the dominant player for REEs.

This approach raises global prices and may create a sense of urgency among importing countries. It could prompt initial investments in extraction, refining, and possibly further downstream infrastructure, but the modest increase in prices and prospects for their reversal does not make major investments viable over the longer term. The presence of this uncertainty introduces hesitation among investors, who may doubt whether high prices and demand will persist once China resumes exports. Essentially, China exerts temporary leverage while avoiding long-term damage to its own processing industry, though this move still harms Chinese exporters temporarily.

However, in a repeat game, these temporary restrictions may be interpreted as likely to be repeated, leading to some countries investing aggressively in anticipation of continued restrictions (or repeat short-term restrictions), regardless of the costs they face in doing so.

5. Strategic Intent: Pressure, Not Collapse

The game theory arguments above suggest that China’s current export controls are not designed for long-term withdrawal of supply from the market but are better understood as a calculated, strategic play in a repeated game. There also is historical precedent for this conclusion. In 2010, China ostensibly cut off REE exports to Japan amid a maritime dispute (Bradsher 2010), causing prices for the REEs to rise and prompting Japan to invest in long-term diversification strategies. In practice, however, reductions in exports were minimal (Kannan and Toman 2025).

The present actions mirror that playbook: assert dominance, signal resolve, but leave room for reversibility to avoid triggering irreversible shifts in global trade dynamics. This strategy maintains enough market dependency to preserve China’s position without triggering a permanent exodus from its processing ecosystem.

In essence, China’s rare earth export controls resemble a “one-shot bazooka” (Clarke 2025), a metaphor highlighting both the potency and inherent limitations of such a strategy. While the initial response may be uncertainty and hesitation among importing countries, overuse of this tactic may prompt permanent supply chain diversification. Indeed, since December 2024, China has banned the sale of germanium, gallium and antimony to the United States—three key minerals that are heavily used in defense applications—causing major US defense contractors to seek a diverse supply of these minerals (Emont et al. 2025). Framing China’s actions this way supports the argument that although the country holds significant influence, its long-term leverage could weaken if adversaries see a lingering and significant threat.

6. Conclusion

The export restrictions imposed by China in 2025 highlight the potential vulnerabilities of REE supply chains, from the ROW’s dependence on China to the need for long-term strategic planning. However, as evidenced by the rapid reversal in China’s REE export restrictions, the tools of game theory and historical evidence suggest that China’s leverage (albeit large) is time sensitive and susceptible to strategic countermeasures.

The path for the ROW to expand REE processing capacity and downstream REE magnet production is not devoid of challenges and is seen as the most significant bottleneck in ensuring a resilient magnet supply chain. China’s current dominant position in the REE value chain is a result of decades of effort. Chinese companies have mastered the technologies needed to separate, refine, and produce REE metal and further manufacture permanent magnets. Though the ROW has been investing in several efforts since the 2010 embargo, it is still playing catch-up and has been unable to become competitive. Once the technological barriers and capital investment challenges to building up a more diversified supply chain are overcome, the question remains as to how competitive production in the ROW would be when compared to Chinese production. Measures taken by the ROW such as investments in alternative supply chains and technological innovation, especially if they are coordinated internationally, will determine whether the current moment becomes a turning point toward supply chain resilience or another chapter in the cycle of strategic dependency.

Current supply disruptions are opening what analysts describe as a “rare earth value gap” (Treadgold 2025) for long-term investors. The potential for pricing premiums and government-backed incentives in ROW markets has sparked renewed interest in scaling previously dormant projects. This outlook suggests that the longer geopolitical uncertainty persists, the more attractive alternative REE ecosystems may become for both private and public investment, an outcome consistent with game-theoretic predictions of strategic substitution.

What is clear overall, however, is that China’s only path to maintaining long-term dominance in the REE market rests on avoiding broad export bans and sustaining cooperative international relations, particularly with countries that view China’s market control as a threat to their supply chain resilience. That said, China’s approach to REE exports has not been uniform; it has at times differentiated between regions, maintaining tighter controls toward some (e.g., the United States or Japan) while continuing stable trade with others (e.g., the European Union), thereby exercising leverage without fully disrupting global supply (Mancheri et al. 2019). As for the ROW, the only viable route to reduce dependence on China is sustained investment across the REE value chain, despite high costs and barriers to entry. Building geographic diversification will require patience and persistence until ROW producers become globally competitive.