Adapting Wastewater Infrastructure to Sea Level Rise: A Review of Coastal State Policies for Septic Systems

Sea level rise and saltwater intrusion pose a challenge to the functioning of on-site wastewater systems. This report reviews how 19 Atlantic and Gulf Coast states regulate and fund these systems, including policies, future planning, and financial support.

Executive Summary

One in five homes in the United States relies on on-site waste disposal systems (OWDS), or septic systems, to manage wastewater. In rural areas, the OWDS share is even higher. Rising sea levels in coastal areas pose a challenge to the functioning of OWDS because the septic drain field, which acts as a filtration system for wastewater, cannot function properly if it has too much water in it. Saltwater intrusion also presents a problem because it can reduce the drain field’s ability to adequately filter nutrients and pathogens.

Although states regulate septic systems through a variety of rules about siting and system design, it is unclear whether they are factoring coastal flooding and future climate change conditions into those regulations. Some government grant and loan programs exist to address wastewater problems, but the degree to which they are used for septic varies across states. In addition, it is unclear whether those funds are being used to address septic challenges specific to coastal areas.

In this report, we take stock of OWDS regulations and funding programs in 19 states along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. We summarize regulations related to OWDS siting near waterways and wetlands or in floodplains and coastal zones and review whether any state is considering future conditions related to sea level rise. We then assess the degree to which each of the states is using its Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) money for septic projects. In the CWSRF Program, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) makes grants to states each year, and states use the funds for low-interest financing arrangements with local governments and other quasi-public entities for investments in wastewater treatment facilities, public sewer lines, nonpoint-source pollution control projects, stormwater management, and more. We tally the spending on OWDS-related projects in each of the states for the most recent fiscal year relative to total CWSRF spending. Finally, we describe additional funding programs that exist in a few states and how they are used for OWDS.

We find that all the states have requirements that septic systems be set back some distance from waterways and wetlands, with the distances varying by state. Most states have limitations on the use of septic systems in designated floodplains or additional system requirements for systems in coastal V zones (100-year coastal floodplains that are subject to storm surge and waves), or both. And finally, most states set minimum depth to groundwater requirements. However, the possibility of exceptions to these regulatory requirements exists in virtually all the states. Only one state acknowledges the impacts of sea level rise on septic systems. In 2021, Virginia passed a law requiring climate change to be considered in septic regulations. At present, those regulations are in draft form and have not been finalized.

Most states use very little of their CWSRF money on OWDS. For the most recent years of data available in states’ CWSRF Intended Use Plans (IUPs) and annual reports, we found that 16 of the 19 states directed less than 3 percent of their total CWSRF spending to OWDS projects. Only three states—Delaware, Florida, and Georgia—used the money to prioritize septic systems. States set up their priority ranking systems in different ways, and these three states have systems that either explicitly or implicitly prioritize OWDS. Delaware, in particular, stands out. According to its FY2024 Intended Use Plan, 24 percent of the state’s spending in that fiscal year was on projects that converted septic properties to public sewer. In our reviews of Project Priority Lists and ranking systems, however, none of the states appear to consider coastal flooding and sea level rise in setting project priorities.

Only four states—Florida, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New York—have funding programs for OWDS. The programs are funded in different ways: by state-issued bonds, general revenues, or special fees. In most of the programs, the bulk of the money is used for septic system repairs and upgrades rather than sewer connections. None of the programs appear to prioritize problems related to sea level rise and flooding.

Our review suggests that despite a growing recognition of the challenges for septic systems in areas subject to sea level rise, regulations and funding programs are not addressing the issue. In part, this likely stems from a limited understanding of the extent and severity of the problem. Most states are not collecting data on septic system location, age, and condition; among our 19 states, only 4—Delaware, Florida, Rhode Island, and Virginia—maintain OWDS databases. Following the lead of these states should be step one for other states. Step two should be to use these data in conjunction with models and maps of sea level rise to better understand who may be affected and where. In devising solutions, revising regulations to consider sea level rise risks, as Virginia is doing, is worthwhile. Finally, the CWSRF Program provides the most reliable and consistent source of funds for states to use for wastewater-related projects, yet most states are not using the program for OWDS. States should reexamine their priorities and consider directing more of these funds to solve septic problems and prevent the problems from getting worse in the future.

1. Introduction

One in five homes in the United States relies on on-site waste disposal systems (OWDS), or septic systems, to manage wastewater (EPA 2014). In rural areas, the OWDS share is even higher. Modern, well-constructed, and properly sited septic systems are acceptable ways of managing wastewater when public sewer is not available. But if an OWDS is not properly maintained or is kept in operation beyond the end of its useful life, a number of environmental and public health problems can arise. Pathogens and nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus can leach into soils, pollute nearby water bodies, and contaminate drinking water wells. If systems are not functioning properly, wastewater can even back up into homes.

In coastal areas, an additional problem of growing concern is sea level rise due to climate change, which is raising groundwater levels, increasing tidal and storm surge flooding, and leading to saltwater intrusion in soils, all of which affect the functioning of OWDS (Cooper et al. 2016; Miami-Dade 2018). A typical OWDS consists of a septic tank and a drain field (sometimes called a leach field or soil absorption field). The drain field acts as a filtration system for pretreated wastewater. When a drain field has excessive amounts of water, it can become too saturated to allow the effluent to percolate down through the soil as intended. The same is true when the groundwater table is too high. In other words, too much water—from above or below—makes the drain field unable to function properly. Saltwater intrusion into soils also can reduce the drain field’s ability to adequately filter nutrients and pathogens.

The full extent of the septic problem in coastal areas is poorly understood because of underlying data deficiencies and a lack of knowledge about local sea level rise. Research studies have assessed the extent of the problem in Miami-Dade County, Florida (Miami-Dade 2018), Maryland (Walls et al. 2023), and Rhode Island (Cox et al. 2019, 2020) by mapping the locations of properties on septic systems with flood zones and sea level rise inundation areas. All the studies find that a substantial share of systems are at risk, though the study regions exhibit variation. Studies in North Carolina and Virginia have also shown that changes in groundwater depth due to sea level rise are presenting a problem (Harrison et al. 2022; Mitchell et al. 2021) and that heavy precipitation events are leading to septic system failures (Vorhees et al. 2022).

Most states have OWDS siting and system requirements that were developed with water quality and public health concerns in mind, but these concerns are magnified by sea level rise, and it is unclear whether state policies acknowledge and address the added problems. In this report, we take stock of state OWDS policies, summarizing state regulatory requirements for the systems and grant and loan programs that can be used for OWDS. Because this study focuses on sea level rise, we look at policies in 19 states along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. We center our attention on policies targeting coastal zones and floodplains, investigating whether states are designing programs to address problems in these areas. We first summarize regulations in each of the 19 states, including siting restrictions based on, for example, flood risk, distance to the coast, and related factors or additional design requirements in these risky locations, such as the use of advanced technology systems. We then turn to policies and programs that provide funding for OWDS repairs and upgrades or conversion of homes from OWDS to sewer. We analyze uses of the main source of funding for wastewater systems in the United States, EPA’s Clean Water State Revolving Fund program, which has provided approximately $5 billion per year to states for wastewater infrastructure over the last 37 years. We follow that with a review of additional state programs that have alternative funding sources.

Substituting advanced systems for conventional ones and moving homes off septic systems and onto public sewer service are two possible solutions to the OWDS sea level rise problem. Advanced systems can operate in slightly different ways, but all involve advanced treatment systems for the wastewater that reduce nutrients, pathogens, or both before the wastewater is released to the drain field. Because an advanced system requires the drain field to do less work, this can be a solution in some coastal settings, albeit a temporary one in places with relatively high rates of sea level rise. Moving homes off OWDS and onto sewer is likely more effective, but it can be costly for homes that are far from existing sewer lines. Furthermore, expanding sewer service can induce even more development and increase exposure to flooding in high-risk coastal areas (Newburn and Berck 2006). A third approach, the most politically challenging, is to buy out properties and relocate people. As sea level rise continues and flooding worsens, causing problems for multiple kinds of infrastructure (Neumann et al. 2015), not just OWDS, relocation may eventually be called for in some areas (Wetlands Watch 2025).

Recognition of OWDS challenges in coastal areas is growing, but they are still given relatively less attention than other coastal climate change problems. And even without sea level rise concerns, OWDS issues often fall lower down the environmental priority list for state and local governments. In our review, we find that states spend a very small fraction of their CWSRF funding on OWDS, and almost no states have other programs that provide funding for OWDS upgrades or conversions to sewer. None of the programs appear to prioritize spending where flooding and sea level rise problems are prevalent.

In part, the lack of attention to OWDS may be because federal requirements through the Clean Water Act, such as National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permits, apply to municipal and industrial wastewater sources of pollution but not to individual OWDS. Additionally, the high cost of monitoring many thousands of individual systems is a deterrent. CWSRF projects are funded through low-interest loans and thus must have a source of repayment, which is another challenge in the case of OWDS. Finally, there is a lack of knowledge about the extent of the problem, with high degrees of uncertainty about the locations of properties at risk under sea level rise and inadequate recordkeeping on septic systems. Filling these gaps will be an important first step in addressing the challenges.

2. State OWDS Regulations

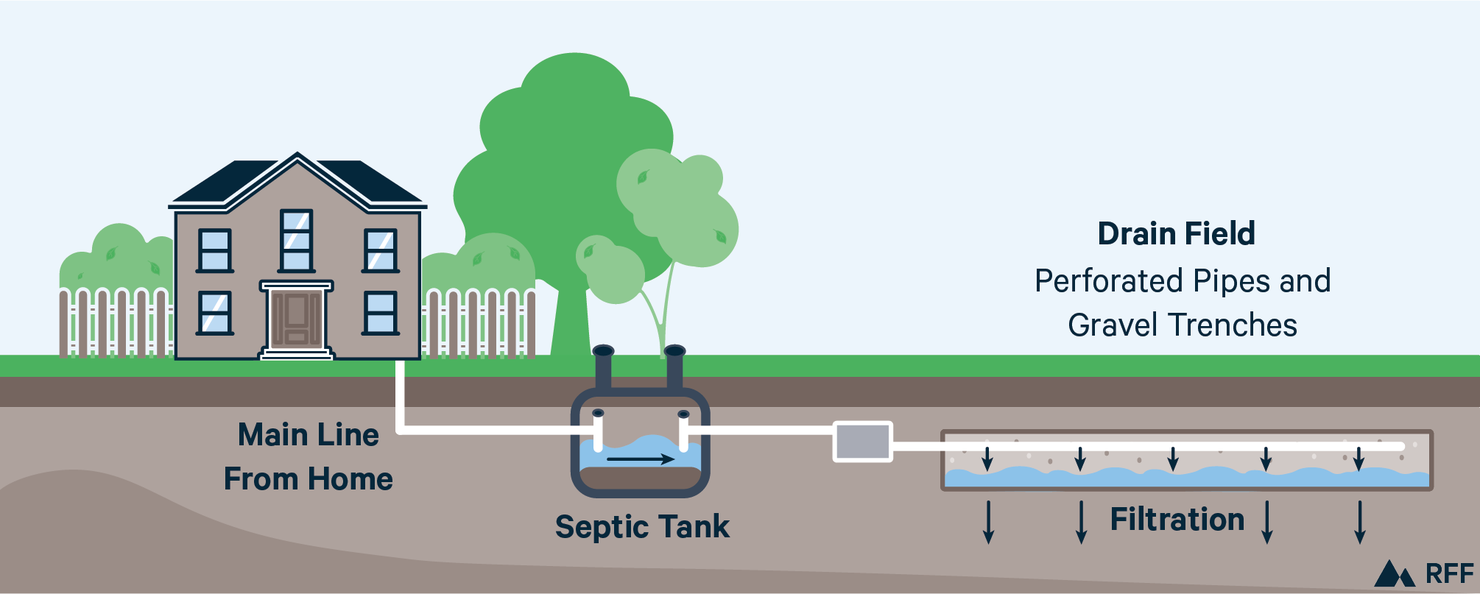

Figure 1 shows a diagram of a conventional OWDS, which consists of a series of drainpipes, a septic tank, a small distribution box, and a drain field. Wastewater flows from the house through a pipe to the septic tank, where solids fall to the bottom, while the liquid effluent flows through another pipe to a distribution box. From here, the liquid is discharged evenly across the drain field, where perforated pipes and trenches allow the effluent to slowly flow into the soil. The solids in the tank must be periodically pumped out, generally every three to five years. State regulations mostly focus on siting of the system but sometimes have requirements specifically for the tank and the drain field.

Figure 1. Conventional OWDS or Septic System

2.1. General State OWDS Regulations

States typically set several regulatory requirements for OWDS. Our reading of state laws indicates that New York, Rhode Island, Maine, Massachusetts, and Mississippi allow for more stringent local OWDS regulations for environmental and health purposes. According to Harrison et al. (2022), however, most state laws do not make clear whether they preempt local regulations. This makes local governments in coastal areas reluctant to adopt stricter requirements, even when they recognize the challenges from sea level rise, for fear of being struck down by the courts. We focus only on state requirements. Websites and other sources for state laws and regulations are provided in Appendix A. While these vary across states, they almost always include system design requirements based on house size (usually number of bedrooms), minimum depth to groundwater, soil conditions, and other site suitability features, such as slope and distance from property lines and drinking water wells; installation requirements, such as licenses for septic contractors; and sometimes maintenance requirements, such as frequency of tank pump-outs. Sale of a property or new construction often necessitates a soil percolation test to ensure that a drain field is functioning properly. In this section, we discuss some of these requirements in more detail, then focus on those specific to coastal zones, floodplains, and other areas with a high risk of flooding in section 2.2.

The design flow of a septic tank is usually determined by the number of bedrooms or the living area of a home. The design flow of the septic tank for a three-bedroom house, for example, ordinarily ranges from 300 to 500 gallons per day. State governments typically provide formulas to homeowners and contractors to calculate design flows based on living area.

Minimum depths to groundwater, measured from the soil surface of the drain field location to the seasonal high-water table, vary from 4 feet in New Hampshire and Maryland to 6 feet in Pennsylvania and up to 24 feet in Florida. Soil evaluations, identifying such characteristics as soil morphology, soil wetness, soil class, and occurrence of rock, are commonly required before the installation of a septic system. The evaluation results help in design and siting of the drain field on the property. Suitable drain field slopes tend to be within the range of 0 to 25 percent; most states have restrictions on siting drain fields on steeper slopes.

States generally stipulate a minimum of 5 to 10 feet between the septic system and property boundaries. Delaware, New York, Texas, and Massachusetts set a minimum distance of 50 feet between septic tanks and drinking water wells and 100 feet between septic drain fields and wells. Maine and Rhode Island set a minimum distance of 10 feet between septic tanks and water supply lines, while the minimum is as much as 50 feet in some regions of New Hampshire. The minimum distance between drain fields and water supply lines is 25 feet in Rhode Island and New Hampshire and ranges from 10 to 25 feet in Maine, depending on the total design flow.

Real estate listings virtually always report whether a home is on public sewer or has a septic system, and most of the states in our sample, with the exception of Alabama and Georgia, have regulations mandating this kind of disclosure. Questions included in disclosure forms usually include the system’s age, frequency of pump-outs, and whether it is currently functioning properly. Massachusetts requires a septic inspection before the sale of a property. While it is the only state with statewide regulation, local governments in several states have such requirements. Typically, if a system is deemed inadequate or a replacement is needed, a soil percolation test is required.

Some states restrict which properties are allowed to have OWDS. For example, the state may require a dwelling that is inside a sewer service area to be connected to the sewer system, though if it was built before the sewer was available, it will often be grandfathered in and allowed to remain on a septic system. In Maine and Georgia, a connection to the public sewer system should be made if the system becomes available within 200 feet of the property. In Alabama, this threshold is 500 feet, but properties must connect only if the OWDS is failing and cannot be repaired to meet state regulations. Florida stipulates that properties connect to new sewer lines within one year of the sewer becoming available, though local jurisdictions are allowed to issue exemptions if the OWDS is functioning properly.

Virginia requires contractors that service OWDS systems to report every service call they make to a centralized database, which is shared with stakeholders and the general public. This requirement has been in place since mid-2020 and provides a unique window into the performance of septic systems statewide. To our knowledge, no other state collects and shares this kind of data. The effort began with reporting only for alternative OWDS systems but has expanded to cover conventional systems as well. The database is available at https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/southside/environmental-health-services/onsite-program-well-and-septic

2.2. State OWDS Regulations for Coastal and Flood-Prone Areas

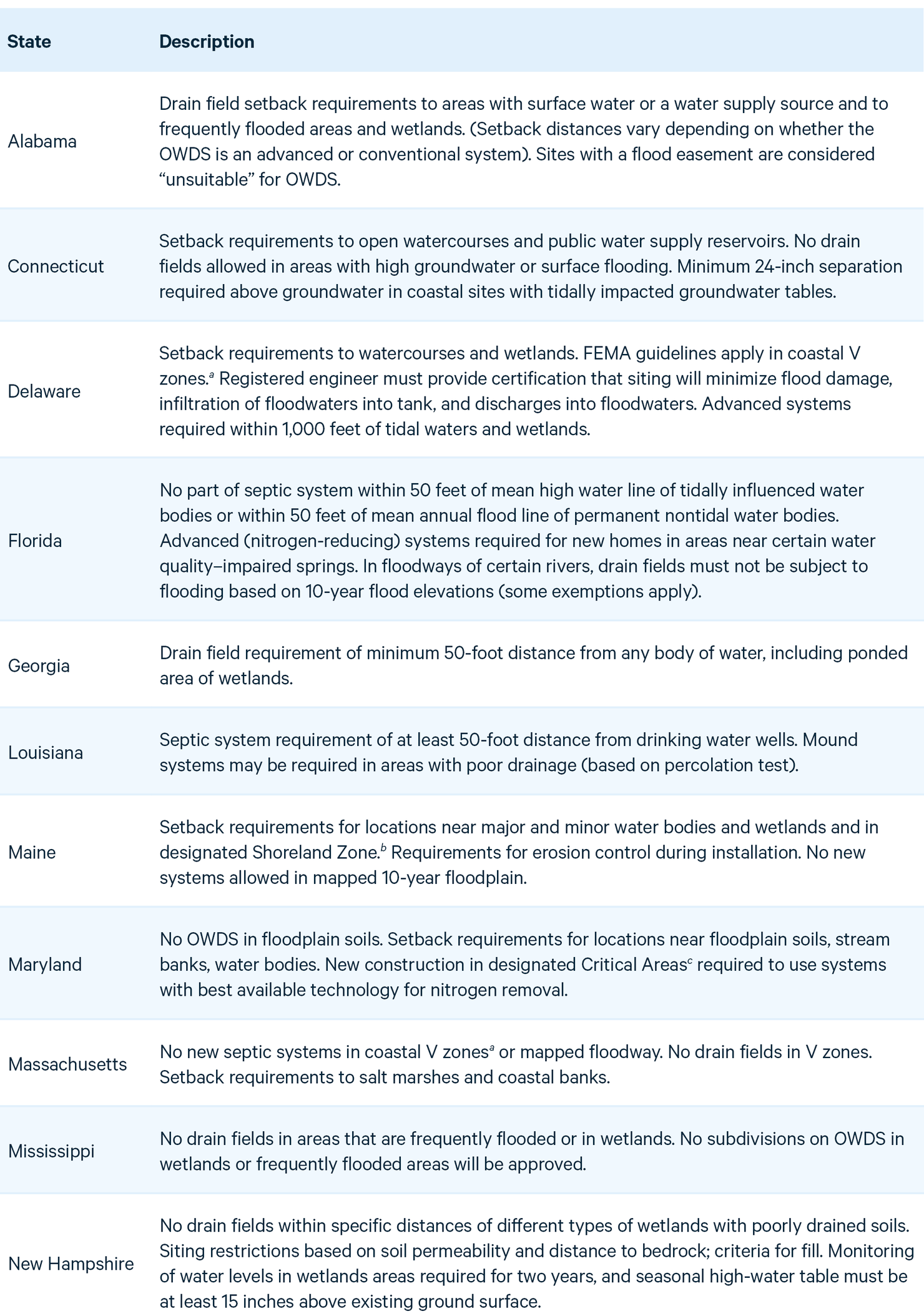

A few states have special regulations for septic systems in flood-prone areas, near wetlands or rivers and other water bodies, or in coastal zones. Table 1 briefly summarizes the requirements in each of the 19 states in our study. Many states require notification of whether a property is in a designated floodplain upon application for a septic permit. We do not include that in the table, as our focus is on siting restrictions, installation standards, and similar rules and requirements that apply in specific areas, rather than simple notification.

Table 1. State OWDS Regulations Related to Flooding, Wetlands, and Coastal Areas

a. V zones are coastal Special Flood Hazard Areas with a 1 percent or greater annual chance of flooding and an additional hazard associated with waves during storms. For V zone FEMA septic guidelines, see Carey (2011).

b. Shoreland Areas in Maine are land areas within 250 feet of high-water line of pond or river, coastal wetlands, upland edge of freshwater wetlands, and lands within 75 feet of high-water line of certain streams.

c. Critical Areas in Maryland are lands within 1,000 feet of tidal waters and tidal wetlands. Maryland has minimum depth to groundwater requirements for OWDS that are less restrictive in coastal counties.

d. Critical Areas in South Carolina are coastal waters, tidelands, beaches, and beach/dune systems.

e. Edwards Aquifer is a major drinking water aquifer in south-central Texas.

Sources for information in this table and in the previous section are provided in Appendix A.

Almost all states have minimum setback requirements for OWDS near various bodies of water and wetlands, though the distances and types of water bodies vary. Some states designate requirements based on floodplain locations or on frequently flooded sites. Most states do not establish outright prohibitions on septic systems in particular areas but set design requirements for such locations. Even where the regulations state that systems should not be located, such as in areas prone to flooding, they often allow for exceptions. Massachusetts is one state that sets strict prohibitions: It does not allow new OWDS in coastal V zones, which are FEMA-designated coastal 100-year floodplains that are subject to wave action and storm surge. South Carolina also has some prohibitions: It does not allow OWDS within certain distances of tidal waters, the mean high-water line of any water body, and designated Critical Areas, which are coastal waters, tidelands, beaches, and dunes.

Even with strict siting requirements, approval is based on preexisting conditions. Sea level rise changes those conditions, sometimes substantially, which might mean that many systems will be unable to deal with the higher water tables despite meeting requirements when installed. Virginia seems to have recognized this problem. In 2021, in response to catastrophic flooding and the problems it was creating for septic systems, the state passed a law requiring the Virginia Department of Health to consider climate change in its OWDS regulations. The Department of Health released draft regulations in August 2024 for public comment. They call for creation of a mapped “critical impact area” in the state that is susceptible to sea level rise and groundwater flooding. The draft regulations direct the Virginia Institute for Marine Sciences to create the map. See Paullin (2024). Within the area, conventional OWDS would have increased setback requirements from shellfish waters (though advanced systems could be exempted). As of the date of this writing, the final regulations have not been released. A Delaware sea level rise advisory committee made recommendations in 2014 that the state consider SLR in regulatory updates for septic systems and drinking water wells (Love et al. 2014). However, we could not find evidence of specific changes that were made in response to these recommendations.

3. Programs and Policies to Address Septic Problems: Funding from the Clean Water State Revolving Fund

3.1. Overview of Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF)

The most important source of funding for state investments in wastewater management is the CWSRF. The CWSRF program, which was created in the 1987 amendments to the Clean Water Act, is administered by EPA. More information on the CWSRF is available at https://www.epa.gov/cwsrf/about-clean-water-state-revolving-fund-cwsrf#works. Each year, EPA makes grants to states, and states use the funds for low-interest financing arrangements with local governments and other quasi-public entities for investments in wastewater treatment facilities, public sewer lines, nonpoint-source pollution control projects, stormwater management (including green infrastructure projects), water conservation and reuse projects, and more. See EPA (2015) for the full list of eligible project types. The bulk of funding goes to wastewater treatment investments. States contribute an additional 20 percent to match the federal grants, and loan repayments recapitalize the fund over time. Interest rates on CWSRF loans are usually below market rates. In 2023, the average interest rate was 1.46 percent, significantly below market rates (EPA 2025b; MSRB 2024). From FY1987 through FY2024, the CWSRF provided a total of $181 billion in funding to states, which led to 51,000 loan agreements for water quality infrastructure projects (EPA 2025a).

EPA requires states to release IUPs each year for the CWSRF funding they receive. An IUP, which is subject to public review, typically includes the composition of total allocated funding for a given year (the bulk of which is the EPA grant and the loan repayments) and a Project Priority List (PPL) that ranks projects based on state-determined ratings. The rating systems vary across states. All states award points for water quality improvements and the associated benefits of those improvements, including human health and environmental benefits, as well as progress toward compliance with state or federal regulations, but the specific numbers of points and weighting across project types vary across states. Projects are often assigned “base” points for meeting particular criteria and may receive “bonus” points or have a “multiplier” applied to their base score for additional outcomes, such as minimal contribution to growth or improvements to water quality in priority water bodies. States also assign point caps to categories of criteria, allowing projects to reach the maximum point allocation in a given category through different avenues. Five states in our group of 19 (Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Rhode Island) include climate change considerations in their prioritization schemes, awarding points for relocation of water infrastructure away from high-risk areas or for improving resilience to climate-caused events and phenomena. However, the number of points awarded is a small share of the overall number of points.

States are required to use CWSRF money in financing arrangements with local governments and other quasi-public entities. The arrangements can include direct loans, loan guarantees, and refinancing agreements. They also establish the interest rates on the loans, the repayment period (up to 30 years), and the types of projects funded. Funds that address OWDS are used most often for sewer extension and connection projects (i.e., converting homes on OWDS to public sewer), rather than for upgrades to OWDS systems. Because funds are provided primarily as loans, not grants, a mechanism is necessary for collecting money for repayment. In septic-to-sewer conversion projects, local governments or water/sewer districts can collect tax payments or sewer fees from customers to repay the loans. Repayment for OWDS upgrades, on the other hand, can be more difficult to coordinate. A policy change in 2014 expanded the possibilities for use of CWSRF money for septic system repair and replacement, and EPA has provided guidance to states on how to use CWSRF money for these purposes (EPA 2022). However, as of 2022, Delaware was the only state to make loans directly to individual homeowners for septic upgrades (EPA 2022). In some states, CWSRF funds have gone to other state agencies that have used the money for system repairs and replacements, but this is not common.

3.2. Uses of CWSRF for OWDS

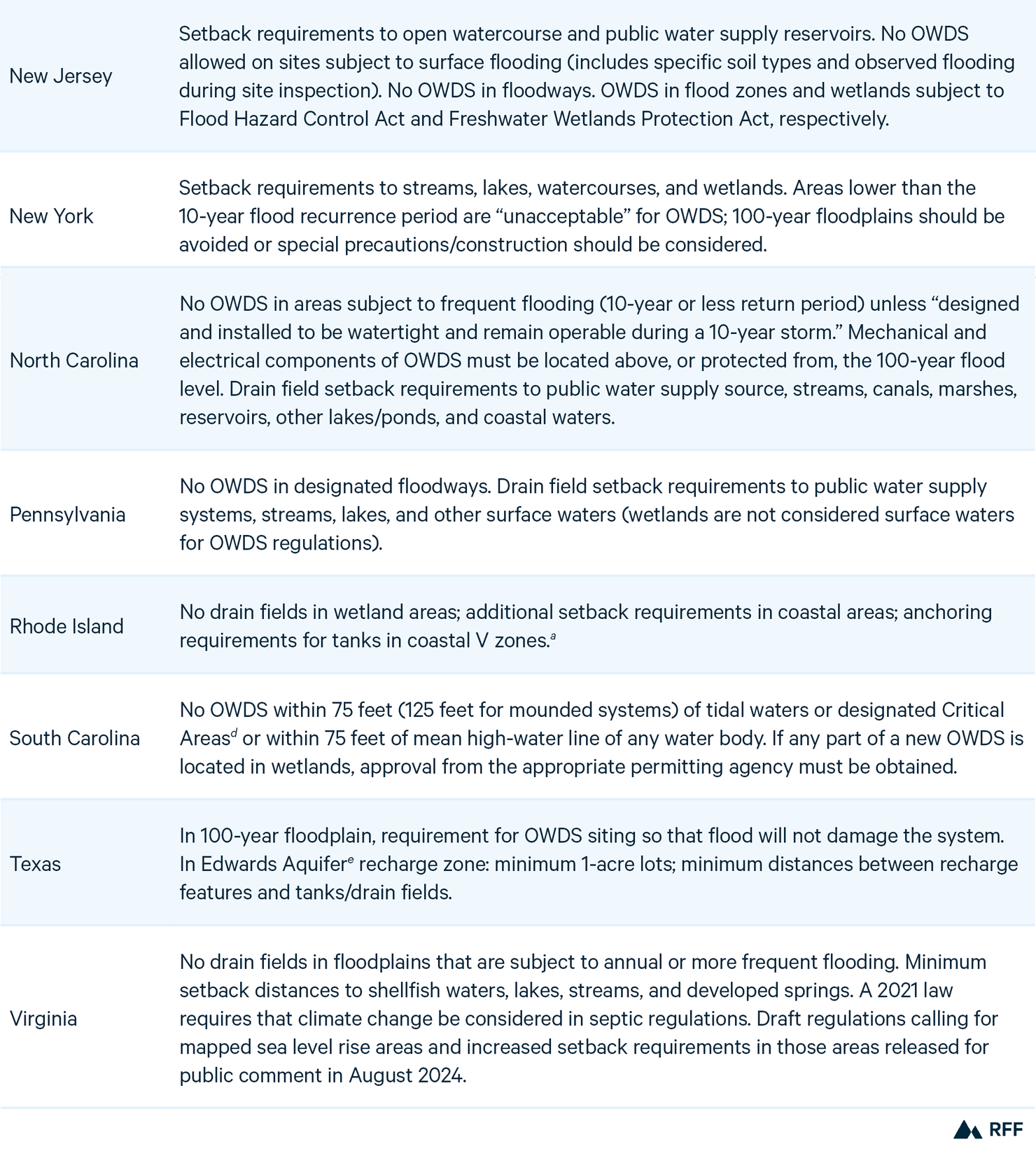

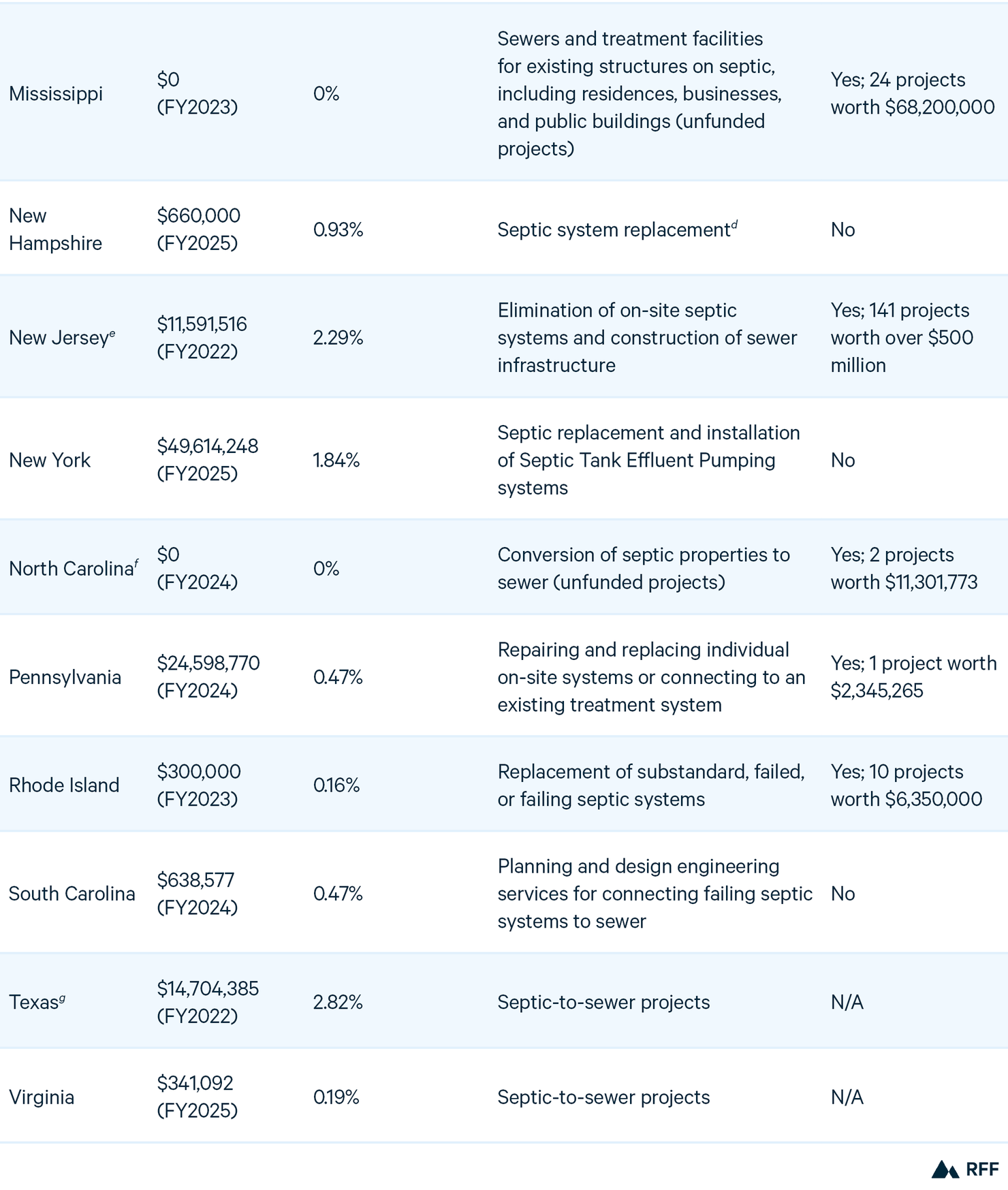

In Table 2, we show CWSRF funds allocated to OWDS-related projects and programs in each of the 19 states for the most recent fiscal year available. We further calculate the OWDS share of the total CWSRF funds that year, according to estimated project funding disbursement, and list the use of the funds from the project descriptions in the IUPs. Finally, we detail the number and total of funds requested for OWDS but not selected for funding to provide a sense of potential unmet OWDS needs in the state. An IUP lists projects selected for the fiscal year, but not all projects end up implemented in that year. States are required to file annual reports with actual spending for the CWSRF. However, we could not rely on the annual reports for our analysis because they were not as readily available for recent fiscal years as were IUPs, and even when they were available, they did not always report spending by individual projects or project types. The two exceptions in Table 2 for which we used annual reports are New Jersey and Texas, whose IUPs did not provide project funding for specific years.

The biggest takeaway from Table 2 is that most states spend a very small share of their CWSRF funds on sewer extensions to replace septic or other septic-related projects. Four states—Connecticut, Maine, Mississippi, and North Carolina—did not allocate any CWSRF project funding at all to septic-to-sewer projects in the most recent fiscal year for which information is available. Seven more—Louisiana, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Virginia—used less than 1 percent of their total CWSRF funding on septic. Five—Alabama, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Texas—used less than 3 percent. Only three states—Delaware, Florida, and Georgia—allocated more than 3 percent of their annual CWSRF project funds to septic. Delaware spent the greatest share by far, at 24.2 percent of its total spending in FY2024. In dollar terms, New York spent the most, at $49.6 million. The median spending across all 19 states was $2 million, 0.9 percent of total CWSRF annual spending.

3.3. What Explains the Differences Across States?

Of the three states that allocated more than 3 percent of their CWSRF project funding to septic repair, replacement, or connection to sewer, Florida’s and Georgia’s priority ranking criteria assign a large percentage of points to outcomes that likely apply to or specifically target septic systems. Florida awards 29.9 percent of its total base points to eliminating an acute or chronic public health hazard like failing septic tanks and to projects that correct septic tank failures. The state also awards bonus points to communities with negative population trends, prioritizing rural areas, which are more likely to be on septic systems. In Georgia’s point system, if a project extends sewer to address faulty septic systems, it is awarded 50 points out of a possible 100. This structure, combined with the fact that the state has only eight individual criteria in its point system (the shortest list of all the states), means that septic-to-sewer projects are naturally elevated on the list of possible projects for funding.

Table 2. Uses of Clean Water State Revolving Fund for OWDS, by State

Note: N/A = not available. See Appendix B for links to individual state IUPs (and annual reports where relevant).

a. The denominator used to calculate the share of spending to OWDS is total expected uses of the CWSRF minus administrative funds in the fiscal year.

b. Connecticut’s project descriptions were too vague to determine whether they included septic-to-sewer or septic repairs and replacements.

c. One project in Maine’s IUP could include a new sewer system for OWDS households, but we were unable to directly attribute any project to septic removal because of vague project descriptions on the PPL. Note that up until 2016, Maine’s CWSRF provided funding for septic system repairs, but because the administrative costs of the repair program exceeded allowable fees for loan repayments, the program was ended. A total of 466 loans for repairs were made over the 20 years of the program.

d. This is a single septic-to-sewer project. A total of $3.8 million was used for two sewer extension projects in New Hampshire, but because it was unclear from project descriptions whether these replaced septic systems (or were for new development), we did not include them in our calculations.

e. New Jersey did not provide an estimated funding disbursement schedule in its IUP that could be linked to specific projects. This calculation reflects actual spending detailed in the FY2022 SRF Annual Report.

f. North Carolina has piloted a Decentralized Wastewater Treatment System Program in partnership with Southeast Rural Community Assistance Project (SERCAP), but potential CWSRF applicants have not yet chosen to apply because, according to the North Carolina IUP, loans can be a barrier.

g. Texas did not provide an estimated funding disbursement schedule in its IUP that could be linked to specific projects. This calculation reflects actual spending detailed in the FY2022 SRF Annual Report.

Delaware awards 10.3 percent of all priority ranking points to septic system elimination. While this is less than is allocated to other types of projects, the state has adopted complementary septic elimination policies and initiatives. Its 2019 Phase III Chesapeake Bay Watershed Implementation Plan lays out goals to eliminate septic systems through sewer annexations over the short term (350 systems by 2020) and long term (600 systems by 2035) (DNREC 2019). In addition, two of the three counties in Delaware have policies that promote conversion of septic to sewer systems, including provision of financial assistance to households. No OWDS projects that applied for CWSRF funds in FY2024 were turned away. Finally, as we reported in section 3.1, Delaware is the only state that uses CWSRF money for direct loans to homeowners for OWDS repairs and replacements (though none of the spending in FY2024 was used for homeowner loans).

Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and South Carolina do not explicitly include OWDS elimination in their criteria. Alabama, Connecticut, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Rhode Island do, but at low shares of the total number of possible points in their ranking systems. In many of the states, more points are awarded for repairs and upgrades to existing sewer systems than for septic-to-sewer conversions or septic system upgrades. New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania each award over 10 percent of total possible points to eliminating failed or malfunctioning septic systems but have other features that act to disadvantage septic projects relative to other types of projects. For example, Pennsylvania requires a proposed sewer service area’s septic system failure rate to be over 50 percent. North Carolina’s and Pennsylvania’s septic points fall into point-capped categories.

It is important to keep in mind that the numbers in Table 2 are for a single year. CWSRF-funded projects of all types, including septic-related projects, can have widely varying costs, so the number of projects funded and the breakdown across project types can vary year to year. In addition, not all projects selected for funding in a given year come to fruition in that year. CWSRF annual reports better reflect actual project spending in a given year, but we relied on IUPs because they are more detailed than most states’ annual reports, providing project-level descriptions and reflecting state priorities across different types of projects. For the three states for which we had both IUPs and annual reports with spending on project types for the same fiscal year, Florida, Georgia and Delaware, we compared the numbers in the two reports. In Georgia, septic projects accounted for 4.4 percent of total spending in the annual report, compared with 9.9 percent in the IUP; in Florida, the annual report showed 7.4 percent of total spending on septic systems, compared with 3.85 percent in the IUP; and in Delaware, the figures were relatively close, at 27.3 percent in the annual report and 24.2 percent in the IUP. Spending can be higher than planned in the IUP because states use the previous years’ funds or lower than planned because planned projects are not completed in the same year. We did not have the time or resources to analyze multiple years of spending. Because states’ priority ranking systems tend to stay the same, however, we believe that the comparisons across states for a single year are indicative of differences in long-run spending priorities.

None of the states appear to prioritize CWSRF-funded septic projects based on coastal flood risks or sea level rise. Even for the three states that spend a significant share of their CWSRF money on septic projects, we could find no evidence that sea level rise risks play any role in project prioritization.

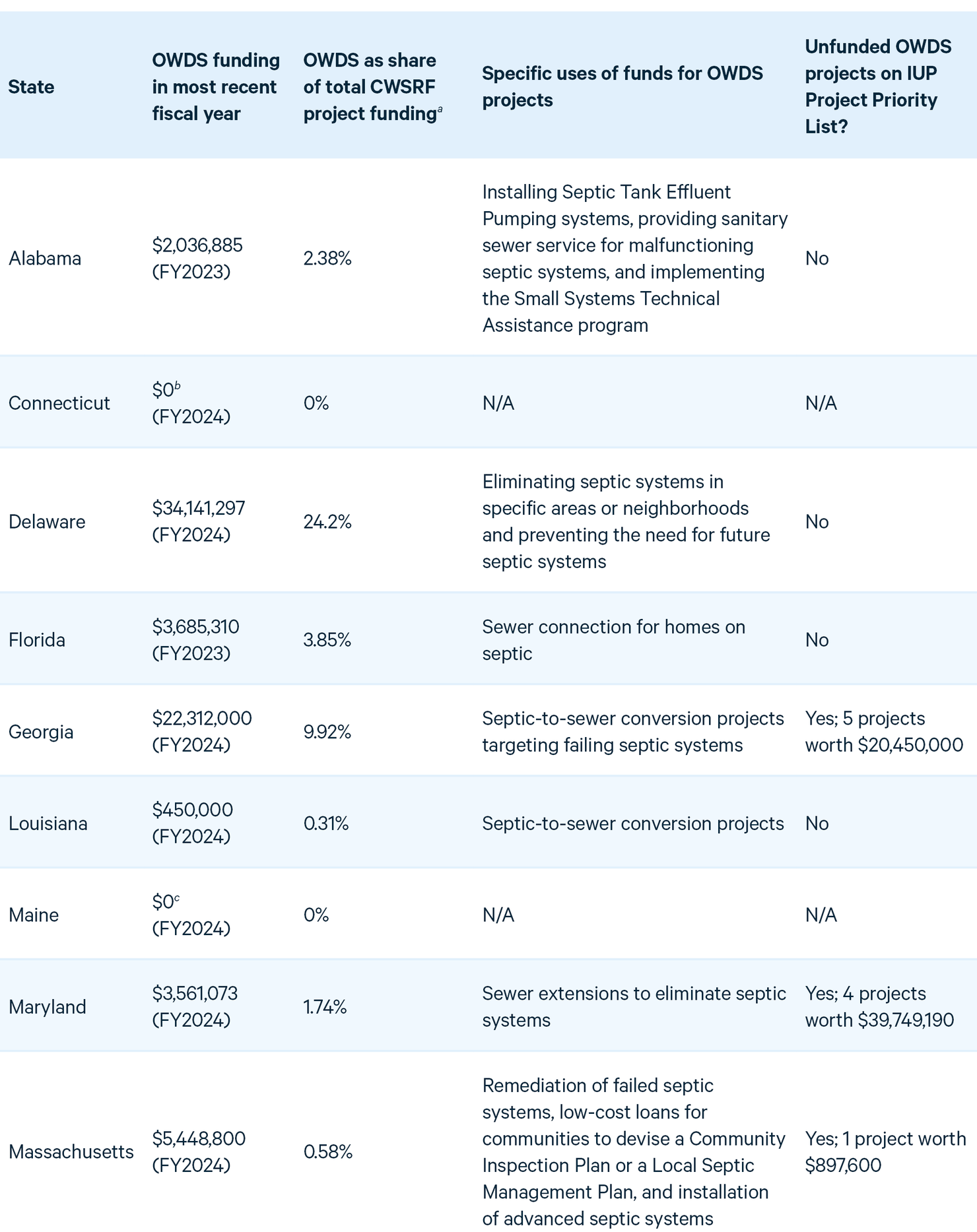

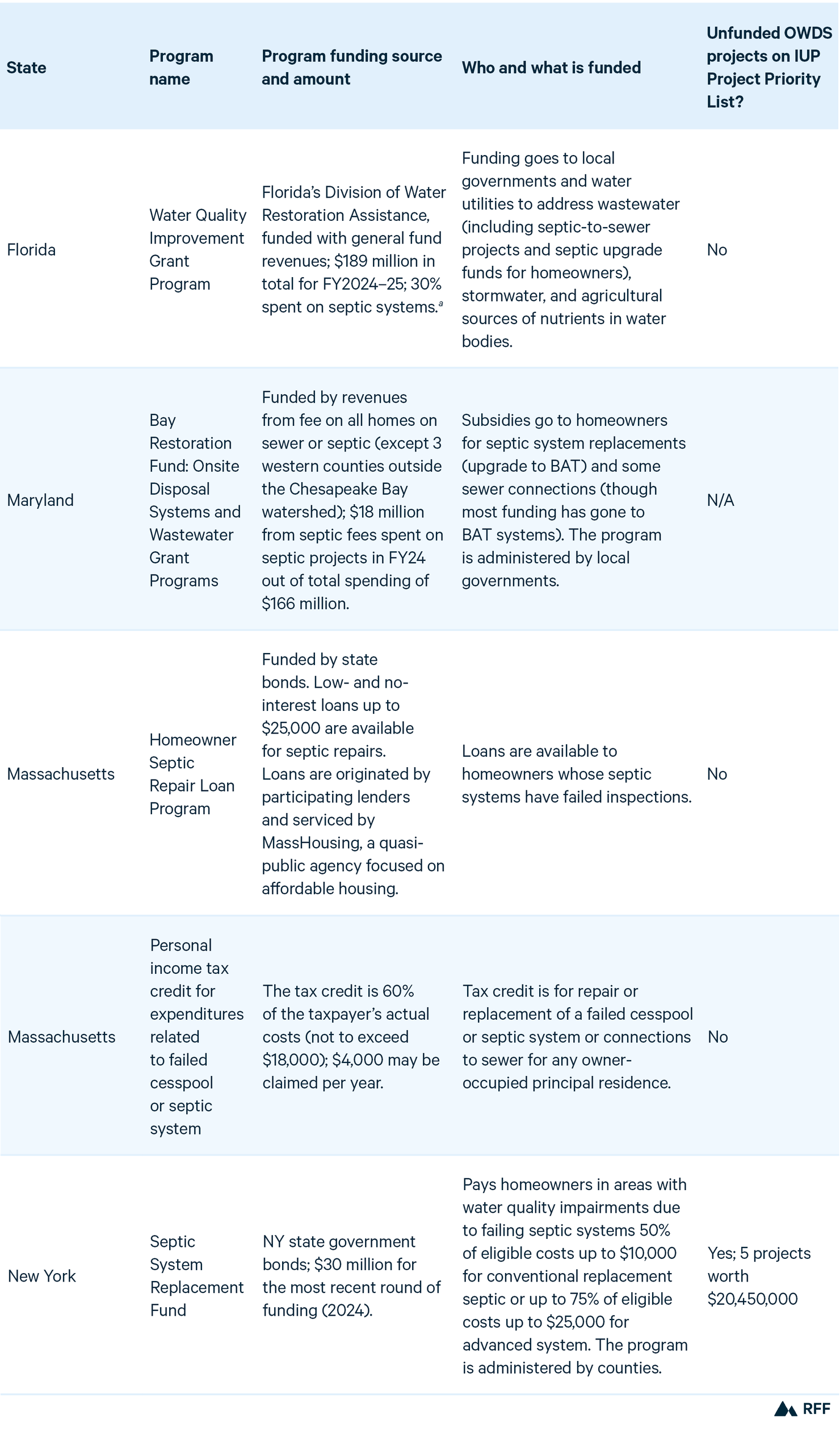

4. Programs and Policies to Address Septic Problems: Funding from Other State Programs

Beyond the CWSRF, a limited number of states have other programs that provide funding for OWDS, usually in the form of grants and low-interest loans and primarily focused on septic repair and replacement (see Table 3). The funds are sourced largely from special state taxes or fees, state-issued bonds, or general revenues. States may sometimes rely on federal funding programs to address septic system issues. For example, North Carolina used roughly $6 million of its FY2022–23 HUD Community Development Block Grant funding for septic-to-sewer projects (North Carolina DEQ 2023). Texas used a portion of its allocation of funds from the federal Clean Water Act Section 319(h) Nonpoint Source Management Grant Program for septic projects, including inventorying systems, paying for pump-outs, and replacing conventional with advanced systems in the state’s coastal zone (TCEQ, n.d.). Because these funding sources are not specifically for septic systems, or even for wastewater projects more generally, and uses of funds can shift widely from year to year, we do not include them in Table 3.

Table 3. Funding Programs for OWDS, by State

Note: N/A = not available. See Appendix B for links to individual state IUPs (and annual reports where relevant).

a. Protecting Florida Together (n.d.).

Four states—Florida, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New York—have programs beyond the CWSRF that fund OWDS repairs, replacements, and upgrades or septic-to-sewer conversions. The programs are funded by state-issued bonds, special fees, or general revenues. Massachusetts has two separate programs: one low-interest loan program and a state income tax credit (in addition to its Community Septic Management Program, which is funded primarily with CWSRF funds). The state’s emphasis on septic systems dates to 1995, when Title 5 of the State Environmental Protection Code was revised and new septic rules were adopted. The state used bond funding to support programs to help homeowners pay, through low-interest loans, for necessary septic repairs and replacements. Massachusetts also has a personal income tax credit for homeowners to repair or replace failed cesspools or septic systems, crediting homeowners up to 60 percent of the cost, not exceeding $18,000 (MDR 1997). Maryland assesses a fee on all homeowners in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, through their sewer bills or property taxes, that goes to a special fund called the Bay Restoration Fund (BRF), used for projects that improve Chesapeake Bay water quality. BRF fees collected from properties on sewer are used for wastewater treatment plant and sewer upgrades while fees from septic properties are used for septic system upgrades and sewer connections. A portion of the septic fees is also used to support best management practices on agricultural land (mainly planting of cover crops). From 2004 through 2024, an average of $13 million per year has been used for 16,315 septic system upgrades to advanced systems and 1,646 home connections to sewer (BRF Advisory Committee 2025). New York’s Septic System Replacement Fund was established through the state’s Clean Water Infrastructure Act of 2017. It is similar to Maryland’s septic program in that counties are awarded funds to assist homeowners. Qualified projects include those that remediate water quality impairment to a designated water body. The program funds up to 50 percent of the cost of septic upgrades or up to $10,000 but does not pay for sewer connections.

5. Conclusions

Recognition of the problems associated with OWDS in coastal areas is growing, but our review of 19 coastal states suggests that regulations and policies designed to address the problem are limited. Siting requirements in most states establish minimum distances to wetlands and waterways, minimum depths to groundwater, and design features for systems located in designated V zones (coastal flood zones subject to waves and hurricane storm surge), but many states offer the possibility of exemptions. Moreover, recognition of future problems due to sea level rise is almost nonexistent, with the exception of a draft plan in Virginia. Yet a growing body of research suggests that sea level rise will put many septic systems at risk in the future.

Solutions to the OWDS problem require money, but we found that most states are not devoting much funding to septic systems, either to help cover the costs of system repair and replacement or to convert septic properties to sewer. The largest source of funding, the Clean Water State Revolving Fund, is typically used for wastewater treatment plant upgrades and other investments; most states spend very little of this money on OWDS. Delaware is an exception; according to its most recent IUP, 24 percent of its annual CWSRF project spending went to OWDS-related projects. Florida and Georgia are two other states that seem to prioritize OWDS, though at levels below that of Delaware.

An important data gap must be filled before the OWDS sea level rise challenge can be fully addressed. State and local government agencies need better information on the location of septic systems, along with their age, general condition, and ideally, repair and tank pump-out history. According to EPA (2022), only four states—Delaware, Florida, Hawaii (not included in our analysis), and Rhode Island—have a comprehensive system of OWDS with location information. Since publication of the EPA report, Virginia has assembled a database. The state also maintains a database of septic system service calls for pump-outs and repairs. To prioritize solutions, the first step is to obtain better data and information on the extent of the problem.

Beyond that, in our view, states should consider how to use CWSRF money for OWDS. This is the largest and most consistent source of annual funding available for addressing wastewater issues in communities. With roughly one-quarter of households on septic systems nationwide, directing more funding to OWDS challenges seems appropriate.