Corporate Due Diligence, Auto Industry, and Battery Supply Chains

This report suggests that the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive is a useful framework for harmonizing existing national-level regulations on the corporate due diligence of critical mineral supply chains.

Abstract

Within the European Union, Multinational Enterprises and their global supply chains are increasingly under scrutiny as consumers and governments demand higher environmental and social standards. In particular, as the green transition accelerates, industries that rely on critical minerals face growing pressure to ensure that their operations are both sustainable and socially responsible. This report examines the implications of the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) for the automotive and battery supply chains, with a focus on how firms may respond to the new requirements. The CSDDD is a European Union-wide legislation, aiming to harmonize national-level due diligence laws that require firms to monitor, report, and address adverse human rights and environmental impacts across their supply chains. We outline the various margins of adjustment that firms have taken, including green investments and supplier monitoring, through digital tools and physical audits. However, we stress that the CSDDD does not specify sector-specific goals to be met by affected firms. Subsequently, we conclude that the directive has potential to transform supply chains, but risks being procedural if its implementation lacks rigorous, measurable targets to track both firm compliance and the aggregate effects of the legislation.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, as the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions has become more salient, public opinion in Europe has shifted in favor of more sustainable consumption choices. Between 2011 and 2019, Europeans not only showed a continuous increase in support for more sustainable practices, but also reported taking more actions to “help tackle climate change” (European Commission, 2023a). This shift in public opinion has exerted significant pressure on policymakers and firms to push for and adopt more sustainable practices, culminating in the introduction of national-level supply chain due diligence laws as early as 2015. However, with the promulgation of multiple laws across national jurisdictions, a clear need arose to harmonize these regulations.

Thus, in 2024, the European Union adopted the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), as part of a broader regulatory effort undertaken by EU policymakers to improve the coherence of its sustainability policies and address human rights abuses in the supply chain of European firms. The directive, similar to many of the individual laws already adopted by certain member states, serves a dual purpose: (a) addressing human rights violations stemming from the activities of large multinational firms abroad and (b) limiting the environmental impacts of those activities (European Commission, 2025b; White & Case, 2025). The date initially set for member states to implement it into national law was 2026.

Although the directive applies broadly to large firms operating within the European Union in various industries, its implications are particularly significant for sectors reliant on critical minerals, especially under the concurrent push for the green transition. Critical minerals such as lithium and cobalt are key to battery energy storage technologies that enable renewable energy generation and the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs). However, many critical minerals are extracted and processed in developing countries, often with adverse socioeconomic impacts on local communities and ecosystems (International Energy Agency (IEA), 2025; Stimson Center, 2023; World Economic Forum, 2024).

Though several regulations for battery and critical materials have already been introduced in the European Union, we suggest that, despite the recent Omnibus proposal limiting its scope, the CSDDD remains a useful framework for harmonizing existing national-level regulations. We explore existing and potential measures of adjustment by affected companies, and the requirements for a successful implementation of the regulation.

2. Current State of the Industry and Regulations

2.1. The Current European Union Battery Supply Chain and Regulatory Landscape

Currently, very little of the battery supply chain lies in Europe, with the most relevant segments concentrated in battery manufacturing; very little extraction of battery critical minerals occurs in the European Union, and limited refining and manufacturing capacity exists. The Kokkola area of Finland accounts for much of the current European capacity, mostly in nickel and cobalt production and refining (Cheng et al., 2024; Torres de Matos et al., 2020; Bruno and Fiore, 2023).

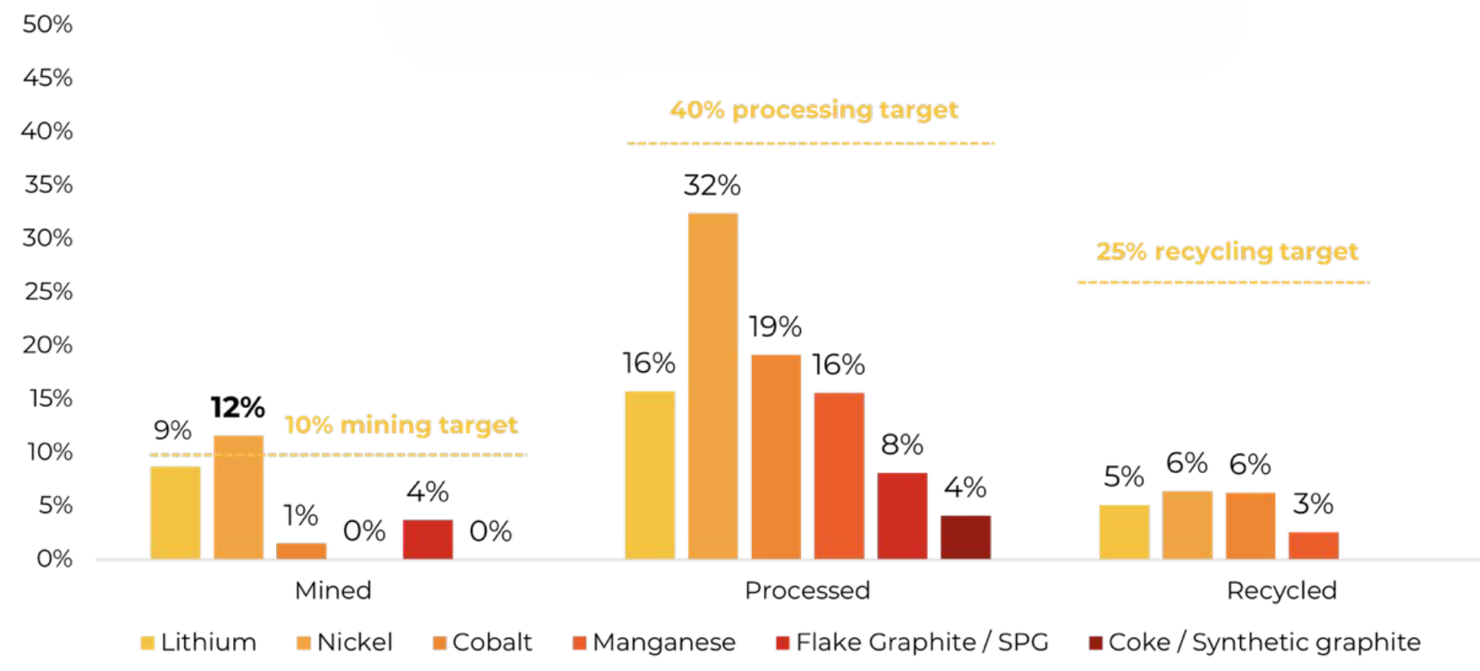

In consequence, the European Union relies heavily on external sources for the critical raw materials essential to its automotive and battery supply chains. Key minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, natural graphite, and rare earth elements are imported primarily from a small number of countries. For instance, Chile supplies approximately 79 percent of the European Union’s refined lithium, while the Democratic Republic of Congo provides around 68 percent of its cobalt, much of which is processed in China, which dominates global refining capacity. Lastly, a large share of refined nickel is still coming from Russia (European Commission, 2023b; Eurostat, 2023; Joint Research Centre, 2023). As seen in the 2024 Annual Battery Report, an industry report published by the Volta Foundation, the European Union is falling far short of the 2030 goals for domestic production stated in the European Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. EU Progress Towards Domestic Mineral Production

Source: 2024 Battery Report (Volta).

These import dependencies create significant vulnerabilities for the European Union’s industrial strategy, especially as demand for EVs and battery materials accelerates. While the CRMA aims to increase self-sufficiency—setting targets like 40 percent domestic processing and 10 percent extraction by 2030—there is no dedicated funding to achieve these goals (European Court of Auditors, 2023). As a result, the European Union is pursuing new trade partnerships and is attempting to diversify supply through agreements with countries including Chile, Argentina, and Indonesia, while simultaneously investing in recycling technologies.

Several regulations for batteries and critical materials have already been introduced in the European Union. The Battery Directive (Directive 2006/66/EC) from 2006 aimed to reduce the amount of hazardous materials in batteries and increase battery recycling rates. This was replaced in 2023 by the New Batteries Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2023/1542), under the auspices of the broader European Green Deal political strategy (European Commission, 2025a). This regulation aimed to minimize the environmental impact of batteries throughout their entire life cycle, from raw material extraction to disposal, including carbon footprint requirements and minimum recycled content requirements (by weight) for cobalt, lead, lithium, and nickel. This regulation also implemented a “battery passport” to ensure compliance and better transparency and tracking of those battery contents.

Furthermore, the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2017/821) was promulgated in 2021, aiming to stem trade in tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold, sales of which have historically been used in part to finance armed conflicts. Lastly, the EU Deforestation-Free Products Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2023/1115), adopted in 2023, asks firms to prove that commodities, including critical minerals, are not sourced from deforested land.

Thus, directives like the CSDDD work to ensure that materials sourced for products sold in the European Union achieve the standards desired by consumers in the region, thereby supporting the focus on sustainable sourcing of imported critical minerals.

2.2. Existing National Supply Chain Due Diligence Laws

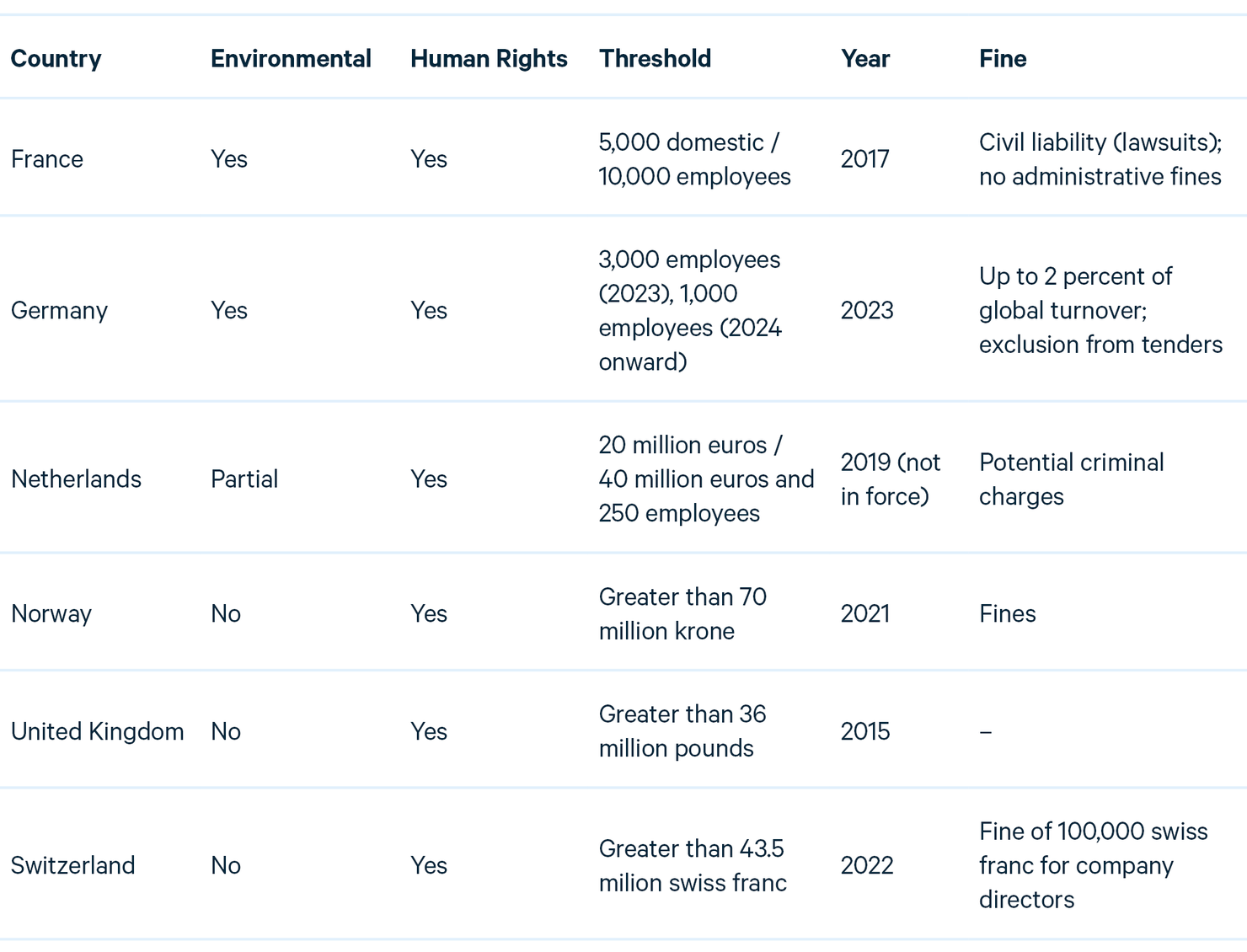

Before the CSDDD was introduced, a number of European countries had already introduced national-level laws aimed at ensuring proper due diligence and best practices within supply chains that underlie the goods sold in their countries. Table 1 presents an overview of the main national laws in place, including their scope—whether they cover environmental issues, human rights concerns, or both—along with the thresholds beyond which companies are liable, the year of introduction, and the specified fines. A number of other countries, such as Ireland, Denmark, Finland, and Belgium (Initiative for Sustainable and Responsible Business Conduct, 2025), have signaled strong support for supply chain due diligence legislation and are preparing for implementation of the CSDDD as promulgated in 2024, but have not yet introduced binding national laws. We discuss each country with an existing law in further detail.

Table 1. Overview of Corporate Due Diligence Laws by Country

The United Kingdom was the first country to promulgate such a law, with the Modern Slavery Act in effect since 2015. This was the first law to mandate that large businesses disclose their efforts in addressing modern slavery within their supply chains. The act requires companies to publish annual statements on their actions. While there are no criminal penalties for noncompliance, the government can seek injunctions to enforce reporting requirements. Though the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union in 2016, fully exiting in 2020, this law helped spur momentum for supply chain due diligence in the greater region (UK Parliament, 2015).

Since 2017, France’s Duty of Vigilance Law has required large companies to develop due diligence plans that identify and assess social and environmental risks in their operations and supply chains. These plans must include risk mitigation strategies, and companies can be held legally accountable for damages resulting from insufficient implementation, facing potential civil penalties (Latham & Watkins LLP, 2024).

The Netherlands’ Child Labor Due Diligence Act, adopted in 2019, requires companies to investigate child labor risks in their supply chains and to declare that they have exercised due diligence in addressing them. Noncompliance can result in administrative fines, and repeat violations may lead to criminal sanctions for company directors, including imprisonment (Littenberg and Binder, 2019). However, the law is not yet in full effect.

Norway’s Transparency and Human Rights Act, enacted in 2021, requires large enterprises to carry out due diligence in line with the OECD Guidelines and report publicly on these efforts. The law also grants individuals the right to request information on how companies manage human rights risks. Companies that fail to comply may face enforcement orders and coercive fines imposed by the Norwegian Consumer Authority (DNV, 2025).

Switzerland’s supply chain due diligence regulation, enacted in 2022, requires companies to implement measures to ensure responsible sourcing. Firms must evaluate their supply chains for compliance with human rights standards related to conflict minerals and child labor risks (EY Switzerland, 2025).

Germany’s Supply Chain Act (Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz, or LkSG), which took effect in January 2023, mandates that companies with at least 3,000 employees (starting in 2024, at least 1,000) establish supplier risk management systems. These systems must address concerns such as child labor, unsafe working conditions, and environmental harm. Companies that fail to comply may face fines of up to 2 percent of their annual revenue and be barred from public tenders for up to three years. Firms are required to conduct risk assessments, implement mitigation measures, set up complaint mechanisms, and publish annual reports on their due diligence efforts (Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, 2023).

Collectively, these laws reflect a shift toward increasing corporate accountability for human rights, labor conditions, and environmental sustainability within supply chains. However, it is important to note that none of these laws have specific targets or deliverables, other than publishing annual plans outlining the steps taken by firms to monitor their supply chains. Hence, the primary channels through which the laws operate are (a) increasing the salience of this topic in public discourse and (b) providing interested groups and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) legal grounds to go after noncompliant firms.

The European Commission surveyed business executives, industry organizations, and civil society, to document the perceived motivation for conducting supply-chain due diligence after the introduction of these laws. Interestingly, business executives ranked reputational concerns, investor relations, and consumer preferences the highest, while not placing a large weight on sanctions and fines or judicial oversight stemming from those regulations. On the other hand, civil society and NGO groups seem to be overly optimistic about the legislative power of these laws, despite the lack of specific thresholds and guidelines (European Commission, 2020).

Yet, while reputational concerns seem to be enough of an incentive for businesses to respond to such legislation, multinational companies in particular grapple with differing requirements and restrictions across different countries. This is a primary concern in the European Union more generally and has led to the introduction of laws that attempt to harmonize disparate national approaches in order to lower the barriers to trade within the larger internal market. Cohesive due diligence legislation across the union could be similarly helpful for large European firms.

2.3. Implications for Automotive and Battery Supply Chains

Most of the national laws referenced in the previous section apply broadly to large companies across various sectors but do not specifically mention automotive supply chains. However, given the significance of the automotive industry in Germany, the LkSG has direct implications for automotive manufacturers and suppliers. Companies are required to assess and address risks related to child labor and forced labor in the extraction of raw materials, such as cobalt and lithium, essential for EV batteries. They are also required to address issues of environmental degradation, including pollution and deforestation, associated with mining and production processes. Lastly, they need to address occupational health and safety violations in manufacturing facilities (Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS), 2023).

Switzerland’s Ordinance on Conflict Minerals and Child Labor also directly affects supply chains in the automotive sector. It requires companies to establish a supply chain traceability system, with specific obligations for each category. Firms must document product details, trade names, and information about suppliers and production sites when there is reasonable suspicion that child labor was employed. As for conflict minerals, companies dealing with 3TG (tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold) sourced from high-risk areas must record details such as mineral descriptions, supplier information, country of origin, and, for metals, data on smelters and refiners. If risks are identified, additional information—including mine of origin, processing locations, and tax payments—must be documented. By-products are traceable only up to the point where they are initially separated from primary minerals or metals (Swiss Confederation, 2022).

3. The EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

Business owners and executives have expressed significant concerns about having to comply with a patchwork of laws and standards across different European countries (European Commission, 2020). As a response, the European Union has made an effort to introduce legislation that will homogenize national-level laws on corporate due diligence. Hence, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) was introduced, requiring large companies to “identify and address adverse human rights and environmental impacts, [...] (1) integrating due diligence into policies and management systems; (2) identifying and assessing adverse human rights and environmental impacts; (3) preventing, ceasing or minimising actual and potential adverse human rights and environmental impacts; (4) monitoring and assessing the effectiveness of measures; (5) communicating and (6) providing remediation” (European Commission, 2022).

3.1. Main Objectives and Harmonization of National Regulations

The main purpose of the CSDDD is to standardize the requirements to comply with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s “Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct,” ideally helping multinational companies to homogenize their reporting and sustainability requirements across the European Union. Moreover, the CSDDD requires European firms to put forth climate transition plans that align with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. Lastly, it aims to homogenize the individual laws that European countries adopted at different times (KPMG in Finland, 2024).

Specifically, while the directive entered into force on July 25, 2024, required compliance was delayed due to negotiations. Companies with a global turnover of more than €1.5 billion and more than 5,000 employees in the EU must comply within three years, by 2027. Those with a turnover exceeding €900 million and more than 3,000 employees have four years, until 2028, and companies with a turnover above €450 million and more than 1,000 employees are granted five years, with compliance required by 2029 (European Commission, 2025c). However, the proposal has been criticized as “onerous and in need of simplification,” given the extensive reporting required across the supply chain (Runyon, 2025).

3.2. The Omnibus Proposals

The criticisms leveled against the CSDDD led to intensive lobbying efforts that resulted in the introduction in February 2025 of what came to be known as the Omnibus proposals. The proposals were a set of amendments aiming to simplify and streamline sustainability reporting and due diligence requirements. While these proposals were intended to reduce administrative burdens and enhance competitiveness, concerns have been raised that they could dilute both existing national regulations and the initial CSDDD proposal (KPMG International, 2025).

There are five main ways in which existing national regulations might be diluted. First, the Omnibus proposals suggest that CSDDD would now apply only to Tier 1 (i.e., direct) business partners and not the entire supply chain. Secondly, the required reporting would be carried out only every five years, as opposed to annually, as is the case in much current national legislation. Third, current legislation requires that firms terminate relationships with business partners for which risks have been identified; the proposal suggests removing this requirement. Additionally, the proposal would exclude financial institutions, such that they would no longer be required to decide investments based on similar guidelines. Lastly, the proposal includes a one-year postponement of the effective date of the law (July 2028) (Ropes & Gray LLP, 2024; PwC United States, 2024).

4. Effectiveness of Corporate Due Diligence Legislation

The main purpose of the CSDDD is to change business practices, prompting companies to account for human rights and environmental standards in the supply chain, as well as requiring member states to take steps towards ensuring that they comply. However, the CSDDD does not include clear targets that companies need to meet. Therefore, evaluating the effectiveness of such laws in improving the sustainability of the supply chain is particularly challenging.

4.1. Margins of Adjustment

Firms can respond to such legislation in two main ways: by making capital investments to enable greener production, more sustainable sourcing, or improved working conditions; and by conducting due diligence with their suppliers and subcontractors to ensure that such violations do not occur across their supply chains. Given the difficulties associated with enforcement, the salience of those topics as a result of the introduction of the legislation, and the subsequent reputational concerns that this generates, seem to be key in shaping compliance incentives.

4.1.1. Capital Expenditures

In recent years, European automotive multinationals have made several efforts to invest in sustainability and rights-focused projects in developing countries. For example, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, BMW and BASF, in partnership with Samsung and GIZ, launched the “Cobalt for Development” initiative in 2019. The project aimed to improve labor conditions and implement responsible mining practices in artisanal cobalt extraction (BMW Group, 2019; BASF SE, 2019). These efforts directly address labor and human rights risks, including child labor and unsafe working conditions. In 2021, Volkswagen Group, the second largest automotive manufacturer worldwide, headquartered in Germany, recognized their “responsibility along the entire supply chain, including their human rights due diligence for raw material sourcing and production” (Volkswagen Group, 2021). As a result, the company, along with a consortium of other large car manufacturers, set up the Responsible Lithium Partnership, an organization to foster sustainable lithium extraction in the area of the Atacama Salt Flat in Chile (Volkswagen Group, 2021; Factory Warranty List, 2023; Mercedes-Benz Group, 2024).

Renault, meanwhile, entered a 2022 partnership with Morocco’s Managem Group to secure low-carbon, traceable cobalt for its EV batteries. The agreement includes a new refinery powered 80 percent by wind energy, thereby contributing to both climate and sourcing goals (Renault Group, 2022). In 2023 the Volkswagen Group announced a €1 billion investment in Brazil to expand its electric and flex-fuel vehicle lineup, as part of a broader zero-carbon mobility strategy (Volkswagen Group, 2023).

Similarly, BMW committed R4.2 billion in 2023 to electrify its Rosslyn plant in South Africa for the production of plug-in hybrid vehicles, explicitly supporting the country’s green transition (BMW Group, 2023). Sweden-based Volvo announced a €160 million investment to expand its Hosakote truck and bus manufacturing facility in India. The new plant will prioritize clean mobility and support India’s growing demand for sustainable transport solutions (Volvo Group India, 2025).

These investments illustrate that leading European automotive firms are beginning to invest in green technologies, environmental protection, and the improvement of labor conditions in developing countries. However, whether these actions were a direct result of the due diligence requirements imposed across the European Union is unclear.

4.1.2. Due Diligence Activities

The capital investments outlined above mainly concern new projects, and while they are focused on the use of renewable energy and sustainable sourcing, they do not directly deal with the activity of suppliers and subcontractors. To obtain a sense of the specific actions taken by automotive firms to monitor their supply chains, we reviewed their annually published reports (an obligation stemming from due diligence laws) and we summarize the key takeaways for Stellantis and Volkswagen Groups.

Between 2017 and 2023, Stellantis—through its legacy firms Groupe PSA and FCA—built a progressively more robust supplier due diligence system grounded in risk assessment, third-party audits, and digital monitoring tools. Initially, both PSA and FCA relied on corporate social responsibility-based evaluations covering over 90 percent of their procurement volumes, complemented by corrective action plans and basic supplier codes of conduct banning forced labor and environmental negligence. Over time, they expanded these systems. PSA introduced sustainability indices and whistleblowing mechanisms, while FCA integrated conflict mineral tracking and launched a supplier compliance platform. After the Stellantis merger, these efforts scaled significantly. By 2023, the group was assessing over 100,000 suppliers using EcoVadis (a global assessment platform that rates businesses’ sustainability based on environmental impact, labor, and human rights standards) and had rolled out a real-time digital compliance tracking system. Supplier contracts were updated to mandate carbon footprint reduction, circular economy integration, and adherence to International Labour Organization standards, with high-risk suppliers subject to independent third-party audits (Stellantis N.V., 2025).

The Volkswagen Group followed a similar path. In 2017, the group implemented a supplier code of conduct and carried out basic sustainability audits. Over the next several years, it introduced digital risk mapping tools, expanded audit programs to cover over 90 percent of procurement spending, and integrated AI-based systems to detect violations. By 2023, Volkswagen was auditing over 4,000 suppliers annually, had trained nearly 8,000 direct suppliers on sustainability requirements, and imposed financial penalties for noncompliance. Volkswagen significantly strengthened its labor rights enforcement, with annual human rights risk assessments and targeted monitoring in high-risk sectors like cobalt mining. It also intensified its environmental responsibility, requiring major suppliers to commit to carbon neutrality and renewable energy sourcing, and to integrate recycled materials under expanded circular economy policies (Volkswagen Group, 2025).

4.2. Monitoring, Verifiability, and Data Collection

Though companies are taking action to improve the sustainability of their sourced materials through capital expenditures and monitoring activities, due diligence is often challenging to verify.

For mineral sourcing in particular, tracking mineral flows from the mine to the buyer is crucial. One approach that mining companies have taken to demonstrate their commitment to sustainability is their voluntary adoption of or inclusion in sustainability certification mechanisms, such as the Copper Mark, the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM)’s principles, the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) standard, and Toward Sustainable Mining (TSM). Other voluntary certification programs exist, yet many have been accused of greenwashing (see, for example, Zharfpeykan (2021); Kippenberg and Wilde-Ramsing (2025)). The challenge is that each of these programs approaches assessing and/or certifying the sustainability of mines differently, and the rigor with which they proclaim sustainability at the mine varies widely (Hiete et al., 2019; Tröster and Hiete, 2019). In the context of the European Union’s supply chain due diligence laws, Human Rights Watch (2023) expressed concern about companies relying upon voluntary audits and certifications as compliance mechanisms, as some of these certifications do not guarantee environmental or social sustainability. In sum, reliance upon voluntary sustainability certifications or audits as a simple way of demonstrating sustainability may not actually result in improved outcomes at the mine.

Even in cases where automotive firms respond to the laws and put procedures in place to hold their suppliers to higher standards for human rights and environmental practices, it is virtually impossible for lawmakers to obtain an accurate understanding of the impact of those activities and, in turn, the effectiveness of the laws in improving outcomes at the supplying mines.

Given the challenges of verifying due diligence activities across fragmented supply chains, moving beyond procedural reporting to instituting quantifiable, performance-based metrics against which compliance can be meaningfully assessed would be more likely to improve outcomes. While developing such metrics may require additional mediation so they could emerge through the negotiation process, existing goals and regulations (e.g., the Critical Raw Materials Act, the battery passport) that can be built upon may prove to be a helpful starting point. Relying solely on commitments or audit participation offers limited insight into actual supplier behavior. Instead, due diligence frameworks could require companies to consistently report specific indicators such as carbon emissions per unit of output, volume of water consumed per product, or percentage of electricity sourced from renewable generation, for example. A benefit of these metrics is that they can be tracked across time and compared across suppliers to assess not just compliance, but progress. For labor-related aspects, metrics could include the percentage of workers covered by collective bargaining agreements, number of occupational health and safety incidents per 100 full-time employees, or the ratio of the average wage to the local living wage benchmark.

Importantly, sector-specific metrics reflect the material risks and environmental or social footprints of each industry. For example, in the automotive sector, relevant environmental indicators may include life cycle emissions of battery components, percentage of recycled materials used in vehicle production, or share of cobalt and lithium sourced from certified conflict-free zones. Tailoring metrics to sectoral realities could ensure that due diligence is both effective and proportionate, supporting meaningful oversight and credible enforcement.

5. Mitigating Cost Increases

Given the challenges in enforcement and the ability of manufacturers to fully quantify the impact of their supply chains on environmental and social sustainability, whether the CSDDD, as written and influenced by the Omnibus regulation, will result in measurable environmental and social improvements at the mine level is an open question. Estimating the impact of the policy will be key to understanding its effectiveness, the costs it imposes on manufacturers and consumers, and the impacts it has on vehicle decarbonization pathways.

There are two ways in which the CSDDD could affect the costs of decarbonization pathways. The first is through increased compliance costs, including administrative costs of compliance and fixed costs of shifting suppliers (Joshi et al., 2001; Kinderman, 2020). These manufacturer costs could be estimated with economic vehicle market models that leverage information on vehicle prices and demand (such as the one utilized in Linn (2022)). Alternatively, exploring public filings from companies or conducting interviews could elicit information about the extent to which the CSDDD impacts manufacturing costs; however, companies have generally kept this type of information confidential, so acquiring the information could be challenging. The European Commission predicted a relatively low cost of compliance with the CSDDD—about 0.13 percent of shareholder payouts made in 2023 (European Commission, 2022; van Teeffelen and de Leth, 2025)—although conducting an ex post analysis as described above would be prudent to ensure that these compliance costs remain low.

The second way in which the CSDDD may affect the costs of decarbonization is that improvements in sustainability at the mine extraction and processing points may increase the cost of procuring the minerals. If environmentally and socially sustainable minerals are more expensive, the cost of EVs could increase measurably, potentially slowing down their adoption. Identifying the impact of the CSDDD on mineral prices is thus a first step to understanding how the policy will impact EV adoption.

Importantly, sustainability is a positive good that many consumers value, yet for that value to be realized, vehicle buyers must be made aware of the environmental impacts of their purchases. Consumers’ knowledge that their vehicles were made in a sustainable manner may boost their willingness to pay (Jupiter Chevrolet, 2025); without verifiable information, however, this benefit is lost (Costa et al., 2019). One solution that could support this effort is the battery passport. The battery passport, an idea developed by the Global Battery Alliance (GBA), would provide each battery with a digital tracking of its supply chain. The idea behind the passport is that consumers would have visibility into the sustainability (or lack thereof) of the batteries in their EVs. So far, the GBA has implemented two pilots of the battery passport, which resulted in the release of rulebooks that cover greenhouse gas emissions, labor concerns, biodiversity, and indigenous peoples’ rights. See https://www.globalbattery.org/battery-passport-mvp-pilots/. If implemented and adopted, these passports could increase willingness to pay for sustainable battery extraction, and reduce the consumer welfare impacts that increased prices would create. Ultimately, however, the battery passport cannot eliminate the challenges of tracking and tracing the minerals across the supply chain.

6. Conclusion

The European Union’s CSDDD represents a significant shift in the regulatory landscape governing global supply chains, particularly for industries such as automotive manufacturing that rely heavily on imported critical minerals. While the directive aims to harmonize national laws and elevate environmental and human rights standards across company operations and supply chains, its effectiveness hinges on the ability of firms and regulators to monitor, verify, and enforce compliance. As illustrated by the practices of companies like Stellantis and Volkswagen, industry leaders are already implementing digital compliance tools, supplier audits, and risk mapping strategies in response to reputational and regulatory pressures. However, many of these efforts remain difficult to quantify, and the lack of standardized metrics limits transparency and comparability across firms.

To address this, future success will depend not only on the adoption of comprehensive legislation but also on the integration of measurable, sector-specific performance indicators. Without such concrete metrics and independent verification systems, laws risk becoming procedural rather than transformative. Moreover, given the potential for increased compliance costs to affect consumer prices and slow the green transition, especially in the EV market, tools like the battery passport and better consumer awareness may help align sustainability goals with market incentives. Ultimately, the CSDDD offers a framework with the potential to drive real change—but only if implemented with rigor, data transparency, and meaningful accountability, for which further regulatory steps are needed.