Improving Industrial Data: Status and Future Directions

This report highlights analyses to inform investment and strategy decisions, unlocking greater prosperity in the US industrial manufacturing sector while also identifying gaps in industrial data.

Executive Summary

Investments to advance industrial manufacturing drive US productivity, innovation, global competitiveness, and supply chain robustness. Economic and energy data on industrial manufacturing are fundamental to inform business investment and operation decisions as well as public- and private-sector long-term strategies for economic growth, industrial competitiveness, and technology research and development. Improvements in data could improve these critical decisions about priorities for investment and unlock industrial manufacturing benefits.

This can occur by improving three types of analysis: (1) analysis of capacity expansion — the construction and upgrading of industrial manufacturing, particularly the adoption of new, advanced technologies; (2) analysis of economic growth, including trade flows, labor needs, regional production, and investments; (3) analysis of technology innovation and optimization within facilities and manufacturing clusters.

Improvements in industrial data and analysis could enhance business investment and operational decisions, long-term strategies for economic growth, industrial competitiveness, and technology research and development. While the myriad sources of economic and energy data on industrial manufacturing already support such decisions to an extent, this support is compromised by weaknesses and gaps. These data sources are often disconnected, and each user must invest time to process each data source and establish connections across numerous sources. Economic and energy researchers often build their own datasets at considerable expense, but mechanisms to leverage and combine those efforts are not readily available. In addition, significant data gaps in valuable information limit decisionmakers, such as industrial energy equipment characteristics (vintage, energy use, competitiveness) and the distribution of those characteristics across firms and/or regions.

To address this, Resources for the Future and the National Laboratory of the Rockies convened a workshop in December 2024 that included sessions on data gaps, data requirements, and methods and opportunities for developing new data. The sessions explored the potential of an industrial data “commons” that could leverage and facilitate industrial energy and economic analysis. This document draws from the workshop but is not a report of workshop results, outcomes, or agreements.

Instead, this report offers concepts for improving industrial data to further leverage existing data, set priorities for new and improved data, and advance shared industrial analysis capabilities through development of an industrial data commons. These concepts respond to the potential high value of coordination across a broad range of industrial data stakeholders. Although the precise definition of an industrial data commons remains to be developed, this report describes its building blocks:

- Creating a community of stakeholders,

- Determining priorities for data types,

- Establishing data standards and methods,

- Improving primary data; and,

- Organizing data access and collaboration mechanisms.

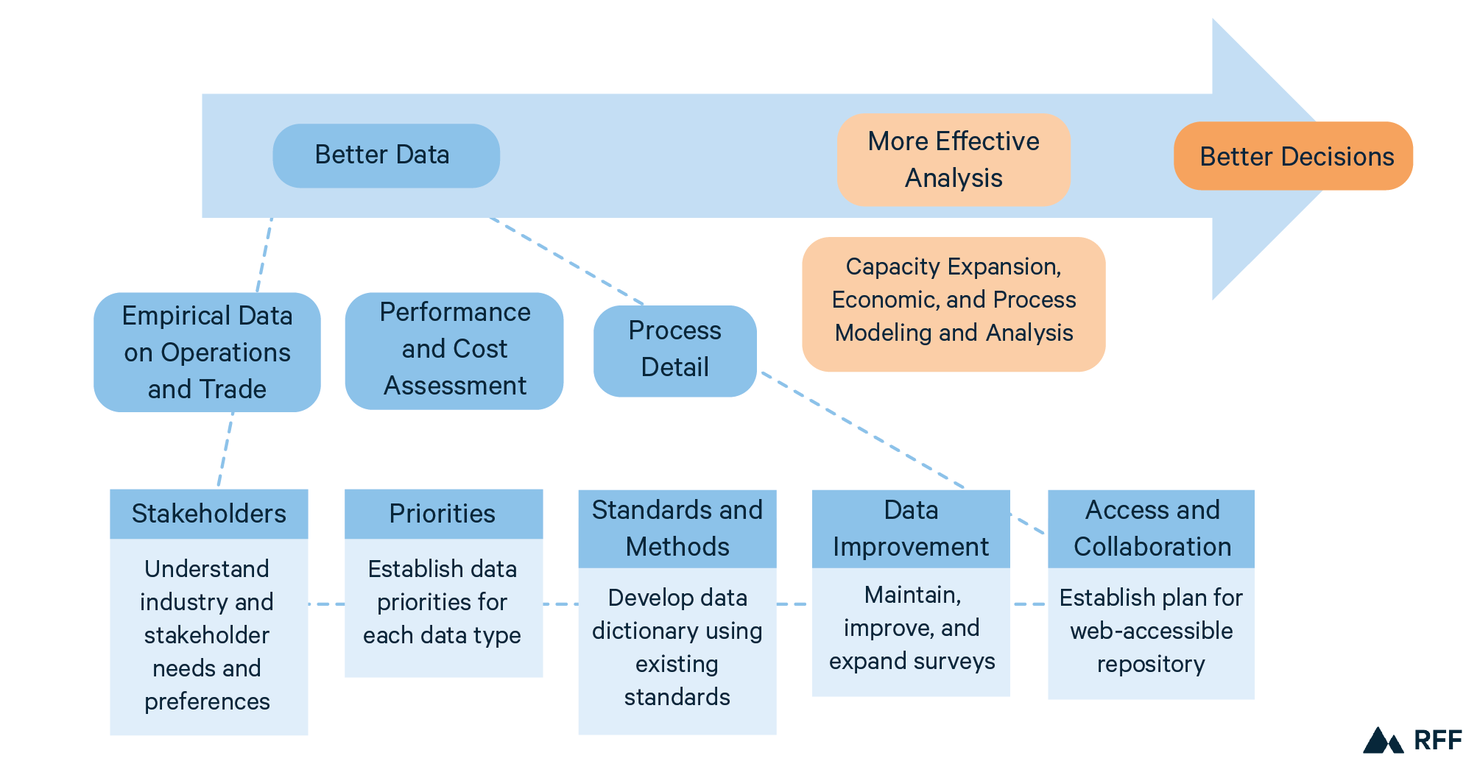

An industrial data commons organized around these building blocks could create substantial opportunities for new industrial modeling and analysis, more informed decision-making, and consequent economic benefits. See Figure ES-1 for a schematic that summarizes the conceptual framework presented in this report. Improved industrial data supports more effective analysis and better policy decisions. The data that meets these needs include current facility data such as capital equipment characteristics and operational data; cost and performance data for incumbent and emerging technologies; historical production, trade, and commodity flows, and projected demands. This report identifies potential priorities and next steps to improve these datasets by developing an industrial data commons, in support of better decisions on industrial investments and strategies.

Figure ES.1. Concepts covered in this report, including steps for establishing an industrial data commons, types of data, and types of analysis targeted for improvement.

1. Data and Industrial Prosperity

Economic and energy data characterizing the US industrial manufacturing sector is an essential resource for decisionmaking by businesses and governments. In an increasingly connected and competitive world, US industry relies on and manages a complex array of supply chains for critical inputs—energy, raw materials, manufactured components—while continually evaluating opportunities and challenges presented by evolving technologies, changes in policy and regulation, and changes in domestic and global commodity markets. Data—whether empirical observations of operations and trade or performance and cost assessments of new technologies—enables the evaluation of these issues and is therefore essential to support both near- and long-term competitiveness in US industry.

Robust data to support detailed modeling and analysis of industry is critical for many stakeholders. An engineer, for example, may be seeking opportunities to reduce energy costs in fertilizer production. An iron and steel firm must forecast the expected costs and revenues realized from development of a direct reduced iron facility. A consultant might need to evaluate potential growth or contraction of cement markets. Or a federal or state policymaker may want to design policies to spur industrial innovation.

Although the information collected by federal agencies, industry groups, consultancies, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) covers many of the critical components, the resulting data sets have limitations:

- Data sets are numerous, disparate, and differ in methodologies and geographic, temporal, or sectoral scope. Such inconsistencies stymie synthesis, forcing some researchers to build their own data sets, at considerable expense.

- Data sets are often aggregated geographically and across industries because of business sensitivity or data collection constraints. Aggregation obscures important differences among regions or subsectors.

- Data collected by private entities is generally behind paywalls and often has substantial restrictions on allowable uses. Data collected by public entities, such as the US Census Bureau, can also be restricted or difficult to access.

- Many categories of valuable data, such as information on specific energy-intensive equipment by facility type, remains uncollected.

In contrast to the power sector, where large amounts of data are collected and made available to the public, the substantial limitations in the industrial sector hinder stakeholders’ ability to evaluate trends, resulting in costs, missed opportunities, and competitive disadvantages.

In December 2024, Resources for the Future (RFF) and the National Laboratory of the Rockies held a one-day workshop, Developing an Industrial Sector Data Commons, to identify data gaps in the US industrial manufacturing sector and to identify and prioritize potential solutions (see workshop agenda, Appendix A). More than 60 research scientists with expertise across economics, energy systems, industrial systems and process engineering, data science, social change, and policy contributed to the discussions. Building on the findings of that workshop, this report lays out the major elements needed to improve industrial data in the near term; it is not a report of workshop results, outcomes, or agreements.

An industrial data “commons” could provide the industrial analysis community—academics, industry executives, technology investors, and government and regulatory policymakers, among others—with comprehensive, detailed, internally consistent, and accessible data. By transforming the way data is collected, accessed, and used, a commons could address the coordination challenges that have hindered industrial energy and economic analysis, thereby advancing our collective ability to understand the opportunities for improving industrial performance and accelerating growth in the United States.

2. Better Data, More Effective Analysis

Data is a foundational resource and US industrial data (see Section 3) has a wide range of audiences and applications. Industry leaders and consultants use data to inform investment and operational decisions. Public sector and national laboratory analysts need information to support policy, regulatory, and program design and to evaluate the results of governmental actions, both past and anticipated. Academic, trade organization, and media analysts use data to study production, employment, wages, workforce needs, trade, and technology evolution. Improved data supporting private and public-sector analyses of energy supply to industry and energy-using industrial technologies would increase precision of analyses and findings on energy-related opportunities. Improved data on production, employment, wages, and trade would reveal implications of technology evolution on potential for growth and workforce needs.

Each potential audience may take a different analytical approach, but having better industrial energy and economic data would improve many analyses. Here, we highlight how better data can improve three types of analysis: capacity expansion, economic modeling, and process modeling. These categories do not represent a comprehensive list of applications of improved industrial data but are examples of the kinds of analysis that are often leveraged in evaluation of long-term technology and industrial economic strategy, including policy and program design.

2.1. Capacity Expansion Modeling and Analysis

Capacity expansion modeling and analysis use techno-economic methods to identify and evaluate mid-term (five years) to long-term (multiple decades) investment and operational strategies. For the industrial manufacturing sector, capacity expansion models (CEMs) typically identify the optimal suite of investments in new facilities by technology, modification or retirement of existing facilities or their components. In addition, these models consider the operation of the system to meet projected demand for industrial products or services, generally based on minimizing costs or some other condition of optimality. Sometimes referred to as “bottom-up” models for their detailed approach, these models are frequently used to inform federal and state policy; develop long-term industrial, trade group, or public plans or strategies; and evaluate drivers of trends in technologies and energy use. The application of CEMs in industry has been more limited relative to other sectors, such as power, largely because of the paucity of granular data.

Improved data for CEM parameterization would be useful at a range of scales and scopes, from detailed subprocess data for a representative process or facility to national-scale data on individual subsectors or the sector as a whole. This data should have greater resolution—spatially and by level of sectoral disaggregation—and should include capacity, energy and material intensities, and operational and capital costs.

2.2. Economic Modeling and Analysis

Modeling and analysis to understand past or potential future trends in trade, employment, wages, prices, and social welfare are key to developing better policies and strategies for growth. Such analyses often leverage “top-down” computable general equilibrium (CGE) models, which range from regional subsector-specific models to economy-wide global models. Results can be used to understand trade flows, labor market dynamics, differences in subnational production, patterns of investment by sector, and interactions among sectors, households, and governments. However, without data on the specific technological and regional variations in industrial manufacturing, these models may misrepresent opportunities or miss them entirely. While capacity expansion analysis can offer more detail on each industrial subsector, general equilibrium analysis addresses the interactions of a sector or subsector with the rest of the economy.

CGE analyses that use more detailed subsectoral and regional data can help policymakers minimize policy interactions or spillovers, and they can alert private decisionmakers to economic opportunities and threats. With sufficiently detailed data, CGE analyses can estimate the effects of economic decisions in one sector or subsector on other portions of the economy.

2.3. Process Modeling and Analysis

Process models use detailed engineering analysis to identify opportunities to improve production processes and evaluate opportunities for innovation and optimization, whether within manufacturing clusters or individual facilities. Detailed process modeling and analysis reveal the opportunities for new technology adoption to benefit individual firms or the economy more generally. Emerging technologies often become competitive first in niche applications, which can only be identified with precise data. This analysis requires physical and chemical characterization of processes to reveal opportunities for optimization. The results are used to design efficient improvements to individual facilities or flows between facilities, in contrast to the assessment of the adoption potential of fixed technology designs in capacity expansion or economic growth analyses.

3. Targeting Data Types, Sources, and Gaps

Participants in the Developing an Industrial Sector Data Commons workshop identified two priority categories of data gaps for modeling an advanced manufacturing sector: empirical data on industry characteristics and operations, and performance and cost assessments for both commercial and emerging technologies.

3.1. Empirical Data on Existing Facilities, Operations, and Trade

Empirical data on the industrial manufacturing sector covers existing facilities’ capital equipment and its characteristics: facility or technology type, capacity, energy and material intensities, operations and maintenance costs, and empirical operational data, including historical production, energy and material use, and product destination (i.e., foreign or domestic).

Publicly available information is collected, synthesized, and published by various federal agencies, such as the Energy Information Administration (EIA), the US Census Bureau, the US Geological Survey (USGS), the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Department of Transportation, the Department of Energy (DOE) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). These agencies’ data sets often provide many insights, but their usefulness can be limited, especially for gleaning insights beyond the purpose for which they were constructed. Data sources and standards are often set by laws concerning an array of interests and matters, and agencies often have discretion in how they define and describe such standards. Further, data standards created to operate in different policy frameworks can lead to the limitations described above.

- Data is inconsistent in scope and categorization. Disparate and numerous sources of data from agencies differ in their sectoral and geographic scope and categorization. Agencies can use inconsistent definitions of categories and boundaries between categories. Sources vary in their approach to combining or separating nonmanufacturing and manufacturing sectors and using North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) definitions. For example, the EIA definition of the “industrial” sector includes all manufacturing, all mining (including fossil fuel extraction), agriculture and forestry, and construction. Furthermore, the frequency and timing of data collection and publication vary across sources, presenting further challenges for data synthesis. In contrast, the US power sector has abundant data collected and published by a limited number of entities (including EIA and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission). The high level of consistency in these agencies’ technological and geographic categories increases the degree of harmonization across datasets.

- Level of data aggregation varies. Some agencies report national and sectoral data; others report data on individual facilities. Generally, data is disaggregated on only one dimension (e.g., spatial, sectoral) at a time. For example, energy consumption data from EIA’s Manufacturing Energy Consumption Survey (MECS) is available by subsector and end-use but aggregated nationally, or it is available by region but aggregated across subsectors.

- Data is incomplete. Data on individual facilities or firms can be obtained from certain sources, but coverage is often incomplete, and as a result, extracting more comprehensive data is time consuming and can create inconsistencies across sectors. For example, SEC filings often include information on individual facilities, but because the data is not tabulated, extracting this information requires processing individual reports.

Industry groups, consultancies, and NGOs also collect and publish valuable data on industry. However, industry groups’ and consultancies’ data sets are typically behind a paywall. As proprietary sources, they place substantial restrictions on allowable uses, limiting their usefulness for researchers with low data budgets or transparency requirements (e.g., many academic researchers). Furthermore, although some consultancies maintain data sets with broad scope and granular detail (e.g., S&P Global’s Chemical Economic Handbook), data developed and maintained by industry groups and NGOs tends to have a more limited scope, such as an individual industry.

Appendix B summarizes selected relevant sources of industry data, their sectoral scope, and their level of aggregation.

Existing sources of empirical data generally allow for aggregate views of industry operations and trade flows. National annual production, energy use by type, and value of shipments by industry subsector, generally at the three-digit NAICS code level, can be relatively easily extracted from existing sources. However, extracting more disaggregated data—by region, sub-subsector (four- to six-digit NAICS codes), facility type, facility, or end-use service—is limited at best. Furthermore, even six-digit NAICS do not sufficiently distinguish between facilities with consequential differences in their energy use or energy technology adoption potentials. For example, NAICS six-digit sector Iron and Steel Mills 331110 includes both blast oxygen furnace and electric arc furnace facilities, despite significant differences in their energy profiles. Further, NAICS codes are not nimble enough to address adoption of new technologies within a six-digit sector over time (for example, cement plants with and without CCUS or pulp mills with or without heat recovery).

Analysts need better empirical data at a high spatial and sectoral granularity, ideally at the facility level. Such data would allow for much more granular evaluation of an array of operational, investment, and trade decisions—both past and potential future—for individual subsectors and facilities.

3.2. Performance and Cost Assessment of Technologies

Another data gap involves the performance and costs of current and emerging technologies: energy and material intensities by type, usable life, maintenance cycles, and other operational characteristics (minimum capacity, minimum run times, ramp rates). Beyond the empirical data on commercial technologies discussed above, technology performance and cost data may take the form of patents, engineering design reports, and techno-economic assessments. These sources are important for technologies that are not well characterized by available empirical data, whether those gaps are due to data incompleteness, data aggregation, or a technology’s precommercial status.

Scientists and engineers in the private sector, academia, and national laboratories develop and publish this information in the course of applied research, development, and deployment, often assessing the cost and performance status of a technology at multiple points during its development. However, this data has several limitations:

- Data sources are inconsistent in their techno-economic assumptions. Challenges in using performance and cost assessments may arise when performance and cost assessments are uncoordinated, or when comparisons across a set of technologies are needed but assumptions or methods, such as financing assumptions or system boundary definitions for energy or cost accounting, are inconsistent.

- Data is insufficient for generalization. Analytic precision requires specifying conditions for techno-economic assessments, such as technology configuration or location of operation. However, if the technology is successful, it may be used under conditions that differ from the case that has been assessed in detail. The sensitivity of performance and cost to these differences may be unknown, particularly for less mature technologies.

- Data inadequately represents uncertainty. In addition to variation in cost and performance across conditions of operation, techno-economic assessments may not adequately represent uncertainties from expected learning and associated improvements in cost or performance, performance risks of new technologies, or supply chain risks.

As with empirical data, sources for performance and cost assessments may be proprietary and have paywalls. Some may be amenable to sharing information that is generalized, even if specific data is not made publicly available.

For these types of data, a critical data step is to collect technoeconomic assessments, characterize and then harmonize their assumptions, and perform sensitivity analysis and uncertainty quantification. The resulting data would provide a basis for technology innovation and optimization as well as for physical and financial validation of the more aggregate perspectives explored through capacity expansion and economic growth analysis.

4. Steps for Creating an Industrial Data Commons

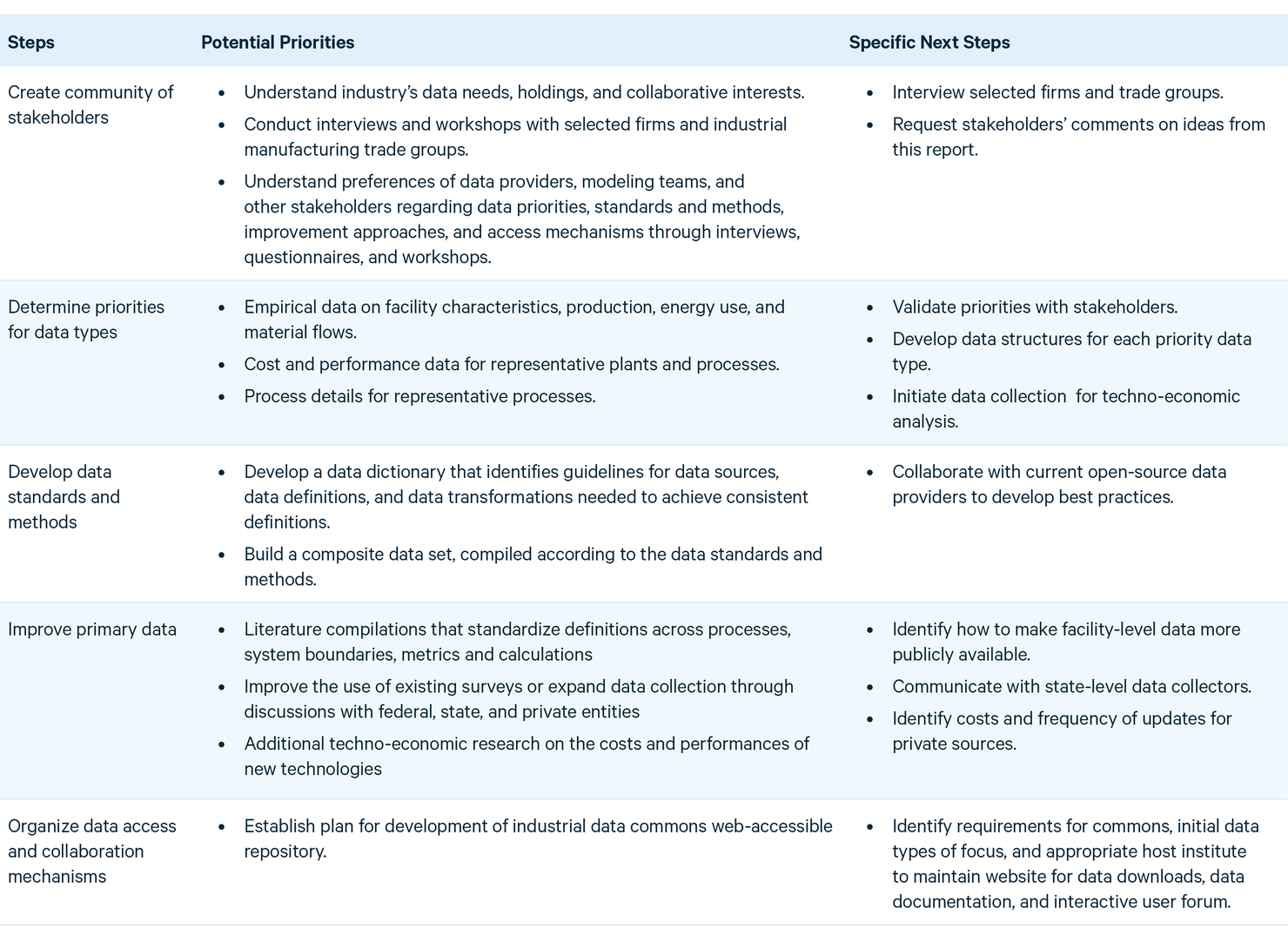

The industrial data commons aims to do more than fill gaps in data; it aims to transform how industrial manufacturing data is developed, published, and used. This goal arises from the observation that coordination across different types of data developers and users could help them build better data products together than any single actor could achieve alone; coordination would also eliminate wasteful, duplicative efforts. The steps to collaborative data development include building a community of stakeholders, setting priorities for data types, establishing data standards and methods, improving primary data, and developing data access mechanisms. We describe each step and explain why it is important and how it could improve energy and economic data on industrial manufacturing. Potential priorities and actionable items related to each step are summarized in Table 1.

Together, these actions could establish an industrial data commons for developing, publishing, and using data.

4.1. Create a Community of Stakeholders

Industrial energy analysts have long observed the challenges of coordination across the many sources and users of data. This observation inspired the workshop, and workshop attendees amplified it. A potential response is to increase communication across industrial data stakeholders, with the goal of improving data coordination. To motivate engagement, such an effort would need to address the data interests of each stakeholder group by understanding their data needs, data holdings, and interests in collaboration. Stakeholders may include individual firms, trade groups, data providers, and industrial analysis and modeling teams.

Actions to build a community of stakeholders could include the following:

- Characterizing data needs, holdings, and expectations related to data collection, access, and use for each stakeholder group;

- Conducting user engagement activities, such as interviews, questionnaires, and workshops; and,

- Refining the value proposition for each stakeholder group in the interests of developing partnerships across private sector, government, and academic contributors to ensure ongoing engagement (e.g., regular meetings) and support.

In the near term, specific next steps could include interviews with selected firms and trade groups to start characterizing data needs, holdings, and expectations. These outreach efforts could include inviting comments on this report to elicit priorities and validate the concepts described here.

4.2. Determine Priorities for Data Types

With a vast realm of possible data types to consider, setting priorities for data collection is essential. Proposed selection criteria could be data for (1) major investment and operational decisions; (2) strategies for economic growth, international industrial competitiveness, and technology options; and (3) analysis of the effects of new or revised federal or state policies and programs.

Data relevant to the first criterion, on investment and operational decisions, would be particularly helpful to individual firms, suppliers, and financers, as well as energy, transportation, and communications infrastructure providers. Data satisfying the second criterion, on growth, competitiveness, and innovation, would assist sponsors of research and development and investors in new technology, including both public and private actors. Finally, data satisfying the third criterion would serve public-sector policy decisionmakers. Data that meet these criteria could be used to inform all of these decisions and improve the effectiveness of investments and strategies for industrial manufacturing.

Feedback during the workshop suggested the following near-term priorities:

- Empirical data on existing facility and facility equipment characteristics,

- Empirical data on production, energy and material use, and domestic commodity flows,

- Empirical industrial commodity trade data,

- Representative cost and performance data on major incumbent and emerging technologies; and,

- Representative process-specific details that underly performance data, such as process flow diagrams at the facility and subprocess level.

Items 4 and 5 are distinct from empirical data because representative plants and processes will likely differ from many specific instances. Item 4 should include an energy balance to provide a strong analytic basis for comparison across technologies and integration with energy analysis. As described in the next step, all of these data types may also be subject to merging, processing, and consolidating. Documentation of methods to develop synthetic data would result in greater completeness.

In the near term, specific actions could include stakeholder engagement to validate these data priorities and development of data structures for each of the selected priority data types. The data for item 4 could be collected in the near term without first resolving the challenges associated with collection of primary data, as required for several of the other data types. A library of techno-economic or cost and performance assessments by process or subprocess and by sector could be developed and hosted as part of the data commons.

4.3. Establish Data Standards and Methods

Inconsistency and incompleteness pose major challenges in applications of industrial energy and economic data. Standards—for example, a data dictionary that extends existing standards, with guidelines for interoperability, compatibility, and coherence across data sets—for data developers to adopt would help address this problem.

Data standards and methods could also address compilation and synthesis of data sources. These methods could cover how to merge, reformat, and develop synthetic data, including imputing higher-resolution data to fill gaps. Application of these methods would result in a data set that is more usable for modeling and analysis than the primary data sets. The workshop participants envisioned:

- Establishing a data dictionary that identifies guidelines for data sources, data definitions, and data transformations needed to achieve consistent definitions; and

- Building a composite data set, compiled according to the data standards and methods, and made publicly available on the data commons repository and website.

A near-term priority could be establishment of a collaboration with open-source data providers to develop best practices for data standards and methods for compilation and synthesis, perhaps including workshops and interviews.

4.4. Improve Primary Data

Better primary data is a prerequisite for advancing industrial data quality. This requires addressing the two issues detailed in Section 3: inconsistencies in the scope, categorization, and resolution of empirical data; and gaps and inconsistencies in performance and cost assessment data. Opportunities and mechanisms to address them include the following:

- Collection and compilation of information from the literature that standardizes definitions across studies;

- Maintenance, improvement, or expansion of existing sources of primary data through new or existing authorizations for appropriate government agencies; and,

- Research and documentation of new techno-economic analysis for costs and performances of new technologies.

Literature compilations are more useful for analysts if standardized definitions—such as categories of processes, boundaries, metrics, and calculations—are followed; this would improve consistency of model input parameters and results. Discussions with data collectors, including federal, state, and private entities, could help identify opportunities to improve the use of existing surveys or expand data collection. For example, the Annual Survey of Manufacturers could be expanded to gather information on capital equipment characteristics. Changes to government surveys are not easy but in the long term could yield the benefits of improved primary data.

Specific near-term actions could include increasing access to facility-level information (available through Census Research Data Centers), engaging with state agencies (e.g., New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, Washington State Department of Ecology, California Air Resources Board, etc.), and assessing private data source cost and cadence.

4.5. Organize Data Access and Collaboration Mechanisms

Effective data access is the final step for an industrial data commons. This entails design decisions to meet users’ needs and expectations, such as the following:

- Transparency of sources (recognizing proprietary issues), estimation methods, and calculations;

- A clear data structure;

- Ability to download data based on selected categories (e.g., sector, geography, etc.) and data quality;

- Tools and guidance for data aggregation; and

- A forum to submit new data, provide user support, and allow users to ask questions of data sources.

Data access is important to ensure usefulness and usability, which will encourage engagement and create a virtuous cycle of interest, support, and engagement.

In the near term, specific actions toward establishing a plan for data access can demonstrate the benefits of a data commons. These include identifying requirements for the commons; planning how to host various data types, with a likely initial focus on techno-economic cost and performance data and composite or synthesized data; and identifying a host institution for the industrial data commons repository and website.

Table 1. Potential Priorities and Next Steps for Better Data

5. Conclusion: Toward Improved Energy and Economic Data on Industrial Manufacturing

Improved energy and economic data could guide decisions about investments and strategies to unlock greater prosperity in the industrial manufacturing sector in the United States. This report highlights the types of analysis that support those decisions but are now limited by data gaps. Filling these gaps requires not only data collection but also collaboration to engage with the broad set of stakeholders who develop and use this information. The steps for collaborative data development—creating a community of stakeholders, determining priorities for data types, developing data standards and methods, improving primary data, and organizing data access mechanisms—can leverage public and private capabilities to improve industrial data. The potential priorities and next steps summarized in this report could set the community on a path toward better-informed industrial investment and strategy decisions.