Droughts in the United States 101

This explainer summarizes the causes and economic impacts of droughts in North America within the context of a changing climate and rising demand for water.

Introduction

Droughts are often thought of as limited to specific places or specific seasonal events, but the reality presents a far more dynamic challenge. Droughts are complicated and often misunderstood events with broad consequences. The US National Weather Service (NWS) defines a state of drought as “a deficiency of precipitation over an extended period” that has adverse impacts on people, animals, or vegetation. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has a broader definition, describing drought as “a prolonged dry period in the natural climate cycle.” Droughts can occur locally or spread across entire regions and countries. Drought conditions typically emerge gradually over months and years, unlike rapid-onset disasters such as tornadoes and blizzards. For example, in the western United States, the average drought-affected area has increased by 17 percent between 2000 and 2022, compared to the second half of the 20th century. The consequences of drought on the economy are far reaching, affecting water quality, public health, and crucial ecosystem services. In this explainer, we will summarize the causes and economic impacts of droughts in North America within the context of a changing climate and rising demand for water.

Types of Drought

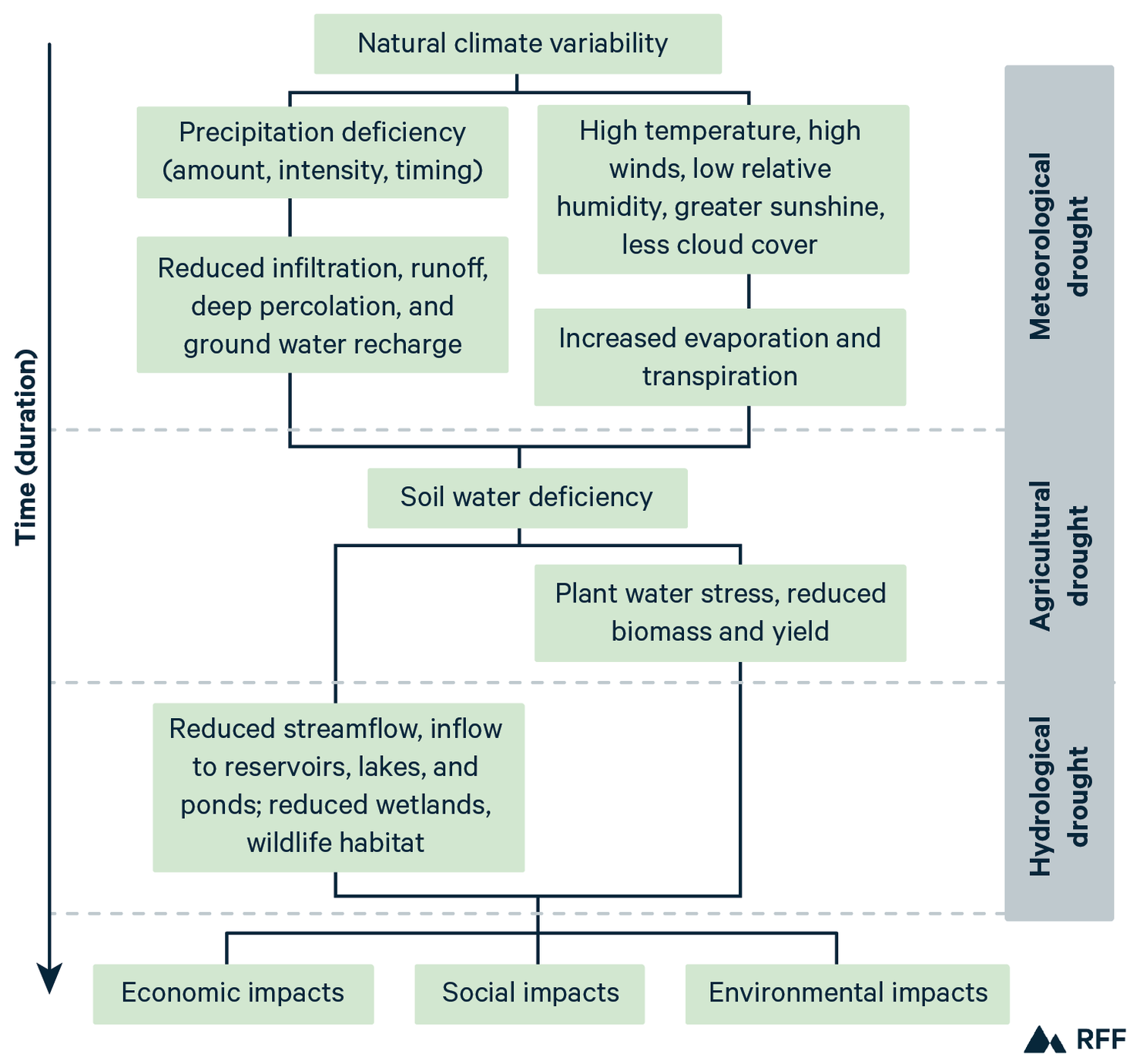

Drought experts typically distinguish between several types of drought, which can be helpful in understanding their causes and impacts.

Meteorological Droughts

Meteorological droughts are caused by reduced precipitation, leading to increased dryness over time. Shifts in wind patterns, changes in ocean temperatures, and natural climate variability can influence routine rainfall. A meteorological drought is often classified as the initial stage of any drought and the point of origin for other drought types as the water shortfall propagates.

Agricultural Droughts

Prolonged dryness can reduce soil moisture, harming plant roots in a phenomenon known as agricultural drought. When the rate of water use by plants exceeds the rate of water uptake from the soil, a water deficit develops. This type of drought may occur relatively quickly, especially during key stages of crop development where plants consume the most water, such as the flowering and fruiting phases.

Hydrological Droughts

Extended disruptions to the water cycle result in hydrological droughts, where natural flows and fill levels in rivers, streams, lakes, aquifers, and artificial reservoirs diminish. Hydrological drought typically develops more slowly than meteorological or agricultural drought, because it takes time for the precipitation deficit to affect these large water storage systems. Added stress from human water usage can heavily influence the severity and duration of this type of drought. Figure 1, prepared by the University of Nebraska’s National Drought Mitigation Center, illustrates the relationship between meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological droughts, as well as their interconnected effects over time.

Figure 1. Stages of Drought and Their Cascading Impacts

Ecological Droughts

The compound effects of meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological droughts ultimately push ecosystems beyond their normal capacities to cope and recover, leading to substantial deteriorations of environmental health and function. Known as an ecological drought, this type of drought involves broader consequences that extend beyond the water cycle, such as habitat and biodiversity losses.

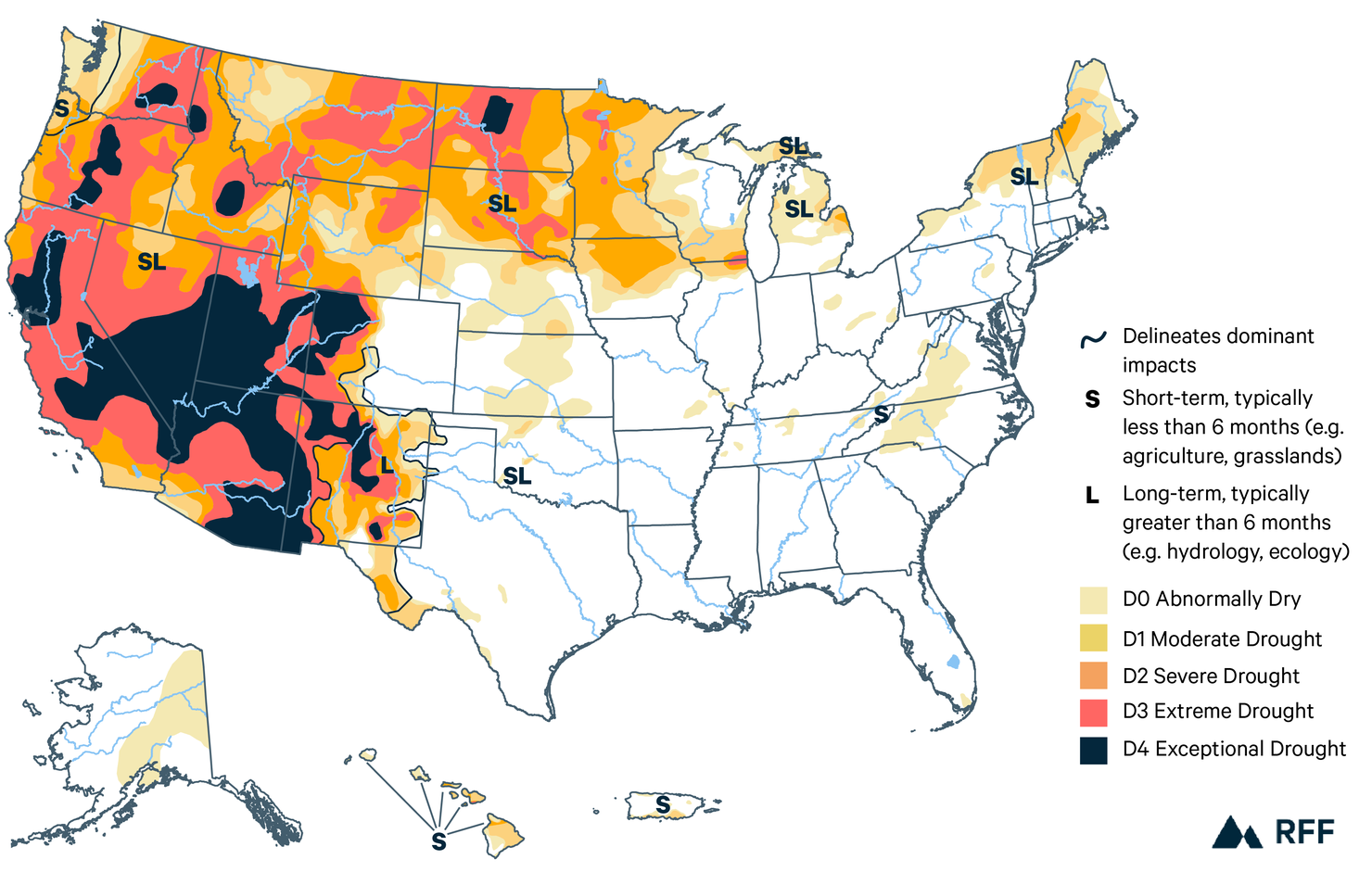

Assessing and Characterizing Drought

Droughts are assessed and characterized using a combination of physical indicators, calculated indices, and on-the-ground impact reports that provide a comprehensive picture of water accessibility and dryness severity. This convergence of evidence helps determine when a region is in drought and the specific type of drought. The most widely used drought assessment tool in the United States is the US Drought Monitor, a collaborative effort by the National Drought Mitigation Center, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The US Drought Monitor includes a weekly-updated interactive map that highlights the severity of ongoing drought conditions and their geographic concentrations. Figure 2 shows the US Drought Monitor map for a week in July 2021, when many Western states were undergoing a period of intense drought.

Figure 2. Map of Drought Status Across the Contiguous United States and Territories

Researchers monitor multiple variables to identify the onset of drought and record the progression of drought scenarios. These methods include comparing precipitation levels in a region to historical averages and using observation wells to check for changes in groundwater levels. Beyond the US Drought Monitor, the Standard Precipitation Index is a widely used drought index that quantifies precipitation deficits or excesses by comparing current rainfall to long-term historical patterns. The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) builds on the Standard Precipitation Index by combining rainfall figures with wind, humidity, and other factors that drive evapotranspiration, the natural process that moves water from surfaces and plants into the atmosphere. To track drought duration and intensity, scientists apply the Palmer Drought Severity Index, which measures relative dryness from a scale of –10 (dry) to 10 (wet). This index synthesizes precipitation, temperature, and soil moisture data into a standardized measure of severity.

National and Regional Drought Trends

The United States has a long-recorded history of drought and its detrimental effects on society and the economy. A 2012 study by the National Drought Mitigation Center found that an average of 14 percent of the United States endured a state of major drought in any given year between 1895 and 2010. Figure 3 illustrates these drought conditions over the last century using the Palmer Drought Severity Index.

Figure 3. Average Drought Conditions in the Contiguous 48 States

The Dust Bowl of the 1930s, which can be clearly identified in Figure 3, is well known as one of the nation’s most destructive drought events. Large dust storms, fueled by extremely dry soil, caused extensive crop failures across the Southern Plains states that exacerbated the economic impact of the Great Depression. When compared to previous decades, the period between 1960 and 2000 brought some relief in the form of wetter-than-average conditions across the United States, while severe droughts continued to occur regionally.

More recently, from late 2020 to early 2023, over 40 percent of the United States mainland was under some level of drought for more than 119 weeks, with a peak of 85 percent in October 2022, impacting western states the most. Current trends indicate that drought is persisting in some eastern and southern regions despite recent rainfall in other parts of the country. Wetter climatic conditions have emerged in the West, but drought has expanded and intensified in parts of the Ohio Valley, Northeast, and Southeast.

Causes and Risk Factors

Precipitation

A drought often starts with an abnormal period of below-average rain or snowfall. Though precipitation varies from year to year across the United States, a drought occurs when this deficiency in water input to the hydrological cycle is less than the water output lost from natural evaporation combined with ecological and human consumption.

Temperature

Temperature anomalies are also a major risk factor because higher temperatures increase evaporation rates. Research has shown that greater levels of precipitation can blunt the impact of temperature increases on drought conditions, with a 2007 study finding that up to 50 percent of the United States would have fallen into “severe to extreme” levels of seasonal drought between the 1990s and early 2000s due to rising temperatures had rainfall been lower. When precipitation is below normal, even moderate temperature increases can significantly speed up the drought process.

Climate Change

Anthropogenic climate change is a risk factor for droughts, both as a threat to regions historically unaffected by drought and to areas that are already prone to drought. A 2024 paper found that climate-driven temperature increases were responsible for 61 percent of the severity of the 2020–2022 regional drought in the western United States. The authors’ future greenhouse gas emissions scenario modeling showed similar-scale droughts increasing from one-in-sixty-year events in the present to one-in-six by the end of this century. In the Southwest, another study from 2022 determined that recent drought conditions were the most extreme in over 1,400 years, with minimal projected odds of full recovery for reservoirs and soil moisture by the mid-21st century.

Socioeconomic Impacts of Drought

Overall Economic Impacts

Droughts are the second-costliest natural disaster in the United States after hurricanes, with the average individual drought costing $11.5 billion in seasonal economic damages. These costs include business interruptions; lost crops, livestock, and timber; damage to buildings and infrastructure; and the cost of emergency relief funding. NOAA’s Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters database identifies 32 recorded regional droughts with combined insured and uninsured losses of over $1 billion between 1980 and 2024, for a total damage cost of $367.6 billion. Figure 4 displays the distribution of drought costs by state, highlighting vast regional differences in the socioeconomic impacts.

Figure 4. Drought Event Losses of Over $1 Billion Per State Since 1980

Agricultural Impacts

The agricultural sector has historically been one of the most sensitive to both seasonal and long-term drought. Drier soils and reduced water availability cause crop wilting and failures, leading to lost farm income, seasonal labor displacement, and supply chain disruptions. For example, a 2019 study found that an additional week of drought could cause up to an 8 percent reduction in corn yields. For livestock and ranching, dry pastures and rangelands force ranchers to purchase expensive supplemental feed and transport water for their animals, substantially increasing operating costs. These production losses and added costs often translate into inflationary food prices, even in states and countries far from the drought region that rely on imported food.

Ecological Impacts

Droughts cause major ecological harms, such as reductions in vegetation growth and increased plant mortality, which can lead to shifts in species composition and even local extinctions. A 2022 paper found that drought conditions were largely responsible for increasing the spread of wildfires in California. Droughts also degrade freshwater ecosystems, reducing stream flow and water quality.

Urban and Residential Impacts

Droughts also affect cities and residents through reduced water supply and quality. These reductions lead to a range of operational challenges for utilities, such as a loss of water pressure, service interruptions, or, in extreme cases, a “Day Zero” scenario where taps run dry. Lower water levels lead to higher concentrations of pollutants, contaminants, and salts, making water treatment more difficult and costly to meet safe drinking standards. Utilities may pass on increased operational costs to residents through rate increases and drought surcharges. In response, authorities may implement mandatory water use restrictions and rationing to manage dwindling resources. These measures frequently include household quotas, usage prohibitions on watering lawns or filling swimming pools, and financial penalties for excessive consumption.

Impacts on Electricity Generation

Droughts impact the electricity sector by reducing hydropower generation, limiting cooling water for thermal energy plants, and creating higher consumer costs and greater reliance on fossil fuels. A 2016 paper estimated the average annual social cost of drought from the energy sector alone to be $51 million per state, with much higher costs in western states that heavily rely on hydropower. Another paper from 2023 analyzed the effects of drought on power plant emissions and the emissions’ consequent impacts on air quality and public health outcomes. The authors found that droughts drove up utility fossil fuel consumption by as much as 65 percent in western states to compensate for diminished hydropower. They connected this fossil fuel consumption to higher air pollution levels, resulting in excess mortality costs of up to two and a half times the direct financial losses of reduced hydropower generation.

Vulnerability

Some human and natural systems are more vulnerable to drought than others. Factors like population density, reliance on agriculture, infrastructure, and drought preparedness plans all contribute to a region’s overall vulnerability. A 2020 paper created a Drought Vulnerability Index to rank US states based on these factors. Researchers determined that Oklahoma possessed the highest drought vulnerability due to outdated preparedness plans and lower irrigation capabilities compared to other states, while California was the least vulnerable thanks to its extensive drought adaptation initiatives supported by a robust economy. Internationally, research published in a 2023 paper showed that developing countries possess the highest levels of vulnerability to drought. The same study also found that 36 percent more of the global population may face drought exposure in the 2050s compared to the present.

Drought Policy Interventions and Governance

The evolution of US drought policy has shifted from infrastructure-focused, reactive responses to a more proactive and integrated approach emphasizing preparedness, demand reduction, and national coordination. Early policies focused on building large-scale water storage to combat drought, particularly for the arid West, as seen with the Reclamation Act of 1902. The Dust Bowl era marked a turning point that established the federal government’s role in providing emergency relief and aid, moving away from the earlier water storage-based model. Modern drought contingency plans, such as a congressionally-approved agreement for the Colorado River in 2019, build on this legacy to update drought policy with consideration for changing environmental pressures caused by climate change and population growth, as well as industrial and agricultural expansion.

State Initiatives

Policy responses to combat droughts vary at the federal, state, and local government levels. The National Drought Mitigation Center maintains a digital public library of state drought plans for 45 states and Puerto Rico. These response and preparedness plans include monitoring and threshold criteria to assess drought conditions, adaptive actions like water conservation mandates and emergency water supply augmentation measures, as well as long-term drought mitigation strategies to improve efficiency and reduce future impacts.

Federal Disaster Assistance and Insurance Programs

USDA provides direct relief and recovery support for drought impacts. The Livestock Forage Disaster Program provides financial assistance to livestock farmers and ranchers who have suffered grazing losses due to drought or fire on federally-managed rangelands. Similarly, the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees, and Farm-Raised Fish Program provides further financial relief opportunities to producers who experience losses from extreme weather or disaster events, such as droughts, in addition to hardship symptoms that can be attributed to droughts, like disease outbreaks.

For crop farmers, federal crop insurance programs provide subsidized insurance for losses that farmers incur due to reductions in crop yields or revenues caused by drought and other natural hazards. These programs are administered by private insurance companies and backed by USDA’s Risk Management Agency. In 2022, the program cost the federal government $17.3 billion, and those costs are expected to increase in the future with climate change. Moreover, the Internal Revenue Service allows farmers and ranchers to defer tax on gains from forced sales of livestock due to drought. The Emergency Watershed Protection Program provides technical and financial assistance to local communities after natural disasters that impair a watershed, including drought. Eligibility for many of these federal disaster assistance programs is determined using information from the US Drought Monitor.

Planning for Long-Term Resilience

Today, economists and water specialists continue to develop governance strategies to meet future challenges. These strategies include modernizing ground and surface water regulation, improving cross-sector data sharing, and linking water policies to broader climate resilience and equity frameworks. Implementing economic tools like water metering and tiered pricing based on consumption levels are options to incentivize residential and commercial users to limit water intake by rewarding efficiency.

Long-term drought resilience planning in the United States is a collaborative effort led by federal agencies through the National Drought Resilience Partnership, which focuses on proactively building capacity at state, Tribal, and local levels. This planning involves coordinating federal resources, improving water management infrastructure, and developing innovative water supply technologies. Through this partnership, the Department of Homeland Security published a 2025 Planning Guide for protecting critical energy and industrial infrastructure from drought. In addition, the Department of Agriculture’s WaterSMART Initiative helps direct federal funding to priority areas in states that require municipal water system upgrades for efficiency improvements and drought preparedness. Multilateral institutions, such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, have also produced frameworks for advancing international drought resilience as part of its annual Global Drought Outlook.

Putting Policy into Practice

While the architecture of drought policy in the United States has become increasingly sophisticated, its effectiveness ultimately depends on how states, local governments, utilities, and water users implement tools. A 2025 report released by the RAND Corporation reviewed the ongoing initiatives taken by five global cities to enhance water security through innovative management and better communication with residents. An example mentioned in the RAND report is how public investment in technological interventions has been gaining significant traction at the state and local levels in the United States. California, Florida, and Texas have embraced desalination, the process of converting seawater into drinking water through filtering or thermal heating, as a supplemental water supply. Cities such as Austin, Texas, and Tucson, Arizona, have made multimillion-dollar investments into nature-based climate solutions that help urban areas retain rainwater and stay cool during droughts. These efforts show that when drought policy is paired with sustained investment and local engagement, it can deliver tangible benefits for climate resilience and community wellbeing.

Conclusion

Droughts are unlike other environmental disasters. They often affect wide areas and have slow onsets that require complex monitoring to track and declare, with spatial and temporal borders that can be difficult to define. As water is a renewable resource, it is easy to ignore long-term water issues until they reach emergency levels, especially in regions that historically receive generous rainfall.

Building drought resilience on a warming planet will require governments, businesses, farms, and individuals to change their relationships with water. For example, governments may need to rethink their agricultural support programs to account for more frequent and longer-term drought episodes, while water pricing schemes may need to change to reflect increased vulnerability to shortages. At the same time, expanding investments into supplemental water sources alongside better coordination across energy, land use, and long-term preparedness strategies can help reduce exposure to drought risks before emergency conditions emerge. The most durable drought mitigation efforts will be those that combine economic incentives, technological innovation, and inclusive governance to manage water security proactively rather than reactively.