How Long Does It Take? National Environmental Policy Act Timelines and Outcomes for Clean Energy Projects

This report analyzes the role of the NEPA review process in utility-scale wind, solar, and geothermal project development.

Read the related NEPA litigation report.

Read the associated press release.

Abstract

Growing demand for electricity and increased interest in affordable clean energy sources have created a rich economic opportunity for renewable energy developers in recent years. However, developers have long expressed frustration with the myriad obstacles to building new generation projects—in particular, selecting a site and securing the necessary leases and federal permits. The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) establishes a process of environmental review that is compulsory for any major action, including the financing of solar and wind projects and construction of utility-scale renewable energy projects on federal lands. Utility -scale projects are projects with a capacity greater than 20 megawatts (AC), as FERC has adopted 20 megawatts as the cut-off for large merchant generators. 20 megawatt or greater capacity is considered competitive for wholesale power markets (NARUC and U.S. AID n.d.; Urban Grid 2019). Its requirements are often mentioned as a major obstacle to renewable energy development, but does the NEPA process significantly delay renewable energy projects? Would adjustments to NEPA accelerate the clean energy transition? We examine the experience for solar, wind, and geothermal power plants that completed the NEPA process from 2009 to 2023 to provide new insights into these questions. Over this period, we find that the solar and wind projects subject to NEPA review account for only a small fraction of the total utility-scale renewable capacity brought online from 2010 through 2023. These renewable projects completed the formal NEPA process in less time than the average time for all project types across all federal agencies. Almost two-thirds of these solar and wind projects did so within one to two years; however, a number of the remaining projects required substantially longer.

1. Introduction

Growing demand for electricity and increased interest in upscaling clean energy sources have created new economic opportunities for energy developers in recent years. In many locations across the country, renewable energy projects are expected to be exceptionally valuable additions to the grid. However, developers have long expressed frustration with the myriad obstacles to building new generation projects. These obstacles include selecting a site for development and securing the necessary leases and permits. We are using “permits” to represent the variety of permitting and leasing actions of the several agencies. For example, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) issues solar energy right-of-way (ROW) “leases” through a competitive process for utility-scale solar energy development within designated leasing areas. It issues solar energy ROW “grants” in response to applications for utility-scale solar energy development. The grant permitting process is not competitive, although BLM may initiate competitive bidding under certain conditions. These processes also apply to ROW approvals for wind projects. For geothermal projects, BLM issues ROW leases (BLM n.d.a, n.d.b; Nedd 2022). For projects developed on private land, diverse state and local laws govern the permitting process, with varying degrees of delay. However, where federal lands or other federal interests (e.g., wetlands or funding programs for renewable sources) are involved, projects are subject to review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) (42 U.S.C. §4321 et seq. (1969)) requires a compulsory environmental review for any major action, including the construction of utility-scale renewable energy projects. The requirements of the NEPA process are often mentioned as a major obstacle to renewable energy development. Even though the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (FRA) amended NEPA with several provisions to expedite NEPA reviews, federal lawmakers continue to explore adjustments. The amendments included page limits and deadlines for environmental impact statements and environmental assessments (Sec. 107(e) and (g); 42 U.S.C. § 4336a(e) and (g)). The Department of Interior recently announced emergency permitting procedures in response to President Donald J. Trump’s declaration of a national energy emergency (The White House 2025). These procedures apply to a variety of energy-related projects, including geothermal energy, but not to solar and wind projects. The procedures would hold the review associated with environmental assessments to completion within 14 days and the review associated with environmental impact assessments to completion within roughly 28 days.

Despite the recent and ongoing changes to the federal permitting process, questions about NEPA review remain. Does the NEPA process significantly delay renewable energy projects? Would adjustments to NEPA accelerate the clean energy transition? What are the trade-offs? This report provides additional evidence to inform answers to these questions. We examine the NEPA permitting process for solar, wind, and geothermal power plants on federal lands from 2009 to 2023 and find that solar and wind projects completed formal NEPA review in less time than the average for all project types across all federal agencies. Almost two-thirds of these solar and wind projects completed the formal NEPA process within one to two years; however, a number of the remaining projects required substantially longer.

Building on previous work by Fraas et al. (2023), who cataloged the utility-scale solar projects that completed the NEPA process between 2009 and 2021, we have added another two years to the database to include solar projects’ status through the end of 2023—a total of 32 solar projects completing environmental impact statements (EISs) and 19 projects completing environmental assessments (EAs) for the 2009 to 2023 period. We have also expanded the database to include 25 onshore wind projects (16 projects completing EISs and nine projects completing EAs) and 16 geothermal projects (three projects completing EISs and 13 projects completing EAs).

2. Policy Context: The NEPA Process

The heart of the NEPA process is developing the environmental impact statement, a comprehensive study of a project and available alternatives for a project likely to have a significant environmental effect. The EIS is intended to provide public officials with relevant information and ensure a hard look at the potential consequences. Each EIS must include a description of the agency’s action, the reason it is needed, a description of the affected areas, and an analysis of adverse environmental effects. It must consider reasonable alternatives to reduce or avoid these effects, along with any irreversible and irretrievable effects. No action can be taken that will have an adverse environmental effect or otherwise limit the choice of a reasonable alternative until the lead agency completes its review and issues a record of decision (ROD) based on the EIS. 40 CFR § 1502.25(b).

To facilitate agency efforts to comply with NEPA, the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) regulations issued in 1978 created two additional categories to identify federal actions that do not require an EIS: categorical exclusions (CEs) and environmental assessments (EAs). In 1978, the Council on Economic Quality (CEQ) issued regulations setting out requirements to implement NEPA. The CEQ rule governed agency reviews—with recent amendments in 2020, 2021, and 2024—for 45 years. However, recent court decisions have found that CEQ lacked the authority to issue binding regulations. CEQ announced on February 20, 2025, that it is issuing an Interim Final Rule rescinding the NEPA regulation and providing implementation guidance for NEPA in its place (Matkins et al. 2025). The renewable projects covered in this paper were reviewed under the provisions of the 1978 NEPA rule. CEs are categories of actions that do not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human environment. CEs are not exemptions from the NEPA process; they require a specific finding by the relevant federal agency. Federal agencies that have established specific CEs for solar and wind projects include the Department of Energy, USDA Rural Utility Development, Federal Aviation Administration, Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and National Capital Planning Commission (CEQ 2018b; 18 CFR § 380.4–5). EAs provide a scoping process to determine whether a project may have a significant adverse environmental effect. The EA process is completed when the agency either issues a finding of no significant impact (FONSI) or determines that an EIS is required. An EA generally consists of four elements: (1) the purpose of the proposed action; (2) alternatives to it; (3) its environmental impacts and alternatives; and (4) the agencies consulted in preparing the EA (BLM n.d.c).

NEPA EIS reviews also typically incorporate other federal agency reviews under other statutes, such as the Endangered Species Act, Clean Water Act, and National Historic Preservation Act.

We identified 32 solar, 16 wind, and three geothermal projects completing EIS reviews and 19 solar, nine wind, and 13 geothermal projects completing EAs over 2010–2023. These projects account for only a small fraction of the total utility-scale renewable energy in that period (EIA 2024). NEPA-reviewed solar projects increased solar capacity by 9,000 MW, roughly 10 percent of the total increase in solar capacity (EIA 2024; DOE 2011a). NEPA-reviewed wind projects increased wind capacity by roughly 4,000 MW, just 3.7 percent of the total increase in wind capacity (EIA 2024; DOE 2011b). Additional geothermal capacity from NEPA-reviewed projects contributed 400 MW—a minor contribution to total renewable capacity. Note that total geothermal capacity declined over this period even with the contribution of 400 MW from new geothermal projects (EIA 2024; Salmon et al. 2011).

From our review, we identified the following takeaways:

- Takeaway 1: Solar and wind projects completed the formal NEPA EIS process in less time than the average time across all project types across all federal agencies. Compared with the CEQ average of 54 months for all project types, solar and wind projects required 27 and 45 months, respectively, to complete the NEPA EIS process (CEQ 2020).

- Takeaway 2: Sixty-two percent of these solar and wind projects completed the formal NEPA EIS process within one to two years. However, average review time is skewed by the substantial number of projects—one-third of the solar projects and half of the wind projects—that exceeded the FRA two-year time limit for completing a formal EIS review. The 2023 Federal Responsibility Act (FRA) established a time limit of two years for EISs and one year for EAs (CEQ 2024). The longest it took for a project in our sample to go from initial action to ROD was 12 years.

- Takeaway 3: For both wind and solar, the time required for projects after completing NEPA EIS review to begin operation (or the duration post ROD but before operation for pending projects as of December 2023) stretched out over four or more years for nine of 24 solar projects and seven of 14 wind projects. These project totals exclude terminated and modified projects.

- Takeaway 4: None of the 16 solar projects for which we have complete information reached full operation from their initial action date within 5 years. Nine of these 16 projects required at least seven years, with three of these projects taking more than 16 years (with two still pending as of December 2023). For the 13 onshore wind projects for which we have full information, three projects began operations within five years of the initial action. However, six projects took at least 10 years after initiating federal agency review to start operation or were still pending operation as of December 2023. Notably, 16 years have elapsed for three pending wind projects from the date of initial action to December 2023.

- Takeaway 5: NEPA EAs on average are completed in less time than agency EISs. However, 13 solar projects (out of 19) and eight (of 12) geothermal projects required more than one year to reach a FONSI from their initial action dates. Despite uncertainty in the initial action dates, these timelines suggest that agencies may find it challenging to comply with the one-year time limit established in the FRA.

- Takeaway 6: Although the documents associated with the conclusion of the NEPA EIS and EA processes are generally available, information on the early stages of agency review and on the additional steps projects take to progress toward operation after completing formal NEPA review is limited. More detailed information on these steps could help better identify causes of delay within the NEPA process.

- Takeaway 7: While we believe we have identified most, if not all, of the renewable projects subject to formal NEPA review, these renewable projects account for only a small fraction of the total utility-scale renewable capacity brought online from 2010 through 2023. For example, NEPA-reviewed solar projects account for only roughly 10 percent of the total increase in solar capacity, and NEPA-reviewed wind projects account for only 3.7 percent of the total increase in wind capacity over the study period (EIA 2024).

The following sections describe our methodology, provide detailed findings on the time required for NEPA EIS and EA reviews for specific solar, wind, and geothermal projects in our sample, and describe gaps in the data.

3. Methodology

We examined federal permitting processes for utility-scale solar, onshore wind, and geothermal projects to identify potential barriers in siting and funding these facilities. We believe our sample covers almost all the utility-scale renewable energy projects completing formal NEPA review for power plant construction located on federal and tribal land over the 2009 to 2023 period. We did not cover NEPA reviews concerned with generation (gen-tie) transmission facilities (where the solar facility was on private lands or where the federal agency tiered off an already completed NEPA review). We excluded any projects that did not complete the NEPA EIS (or EA) process with a record of decision (or a finding of no significant impact). We relied on the final EIS and EA plus the ROD and FONSI as the primary information sources, but we also used documents from other federal and state agencies, newspaper and trade press articles, and publications from nongovernmental groups.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) maintains the Environmental Impact Statement Database, which has information about EISs prepared by federal agencies, as well as EPA’s comments concerning the EISs. In addition, the primary agencies involved in the reviews—Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Department of Energy (DOE), US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), and US Department of Agriculture Rural Utility Service (USDA RUS)—have centralized databases with documents like the final environmental impact statement (FEIS), ROD, final environmental assessment (FEA), and FONSI. The agencies’ NEPA registers are available online: BLM, https://eplanning.blm.gov/eplanning-ui/home; DOE, https://www.energy.gov/nepa/nepa-documents; USACE, https://www.mvn.usace.army.mil/Environmental/NEPA/; and USDA RUS, https://www.rd.usda.gov/resources/environmental-studies/assessments. We were not able to identify a central source for Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) reviews. Moapa Indian Tribe provides a website that covers the EIS and ROD for the several projects on its Nevada reservation: https://www.chuckwallasolarprojectseis.com/previous-eiss.html.

In addition to the centralized agency sites, we used a Google search on the project name to gather general information. If any details were missing, such as the notice of intent (NOI) date to initiate an EIS review, we refined the search using terms like “Project Name” + “NOI” to find relevant documents. For NOIs, this approach would generally locate the Federal Register notice. We provide citations for sources by project in a supplemental document, including court information relevant to our subsequent report.

4. Results for Environmental Impact Statement Reviews

4.1. Utility-Scale Solar

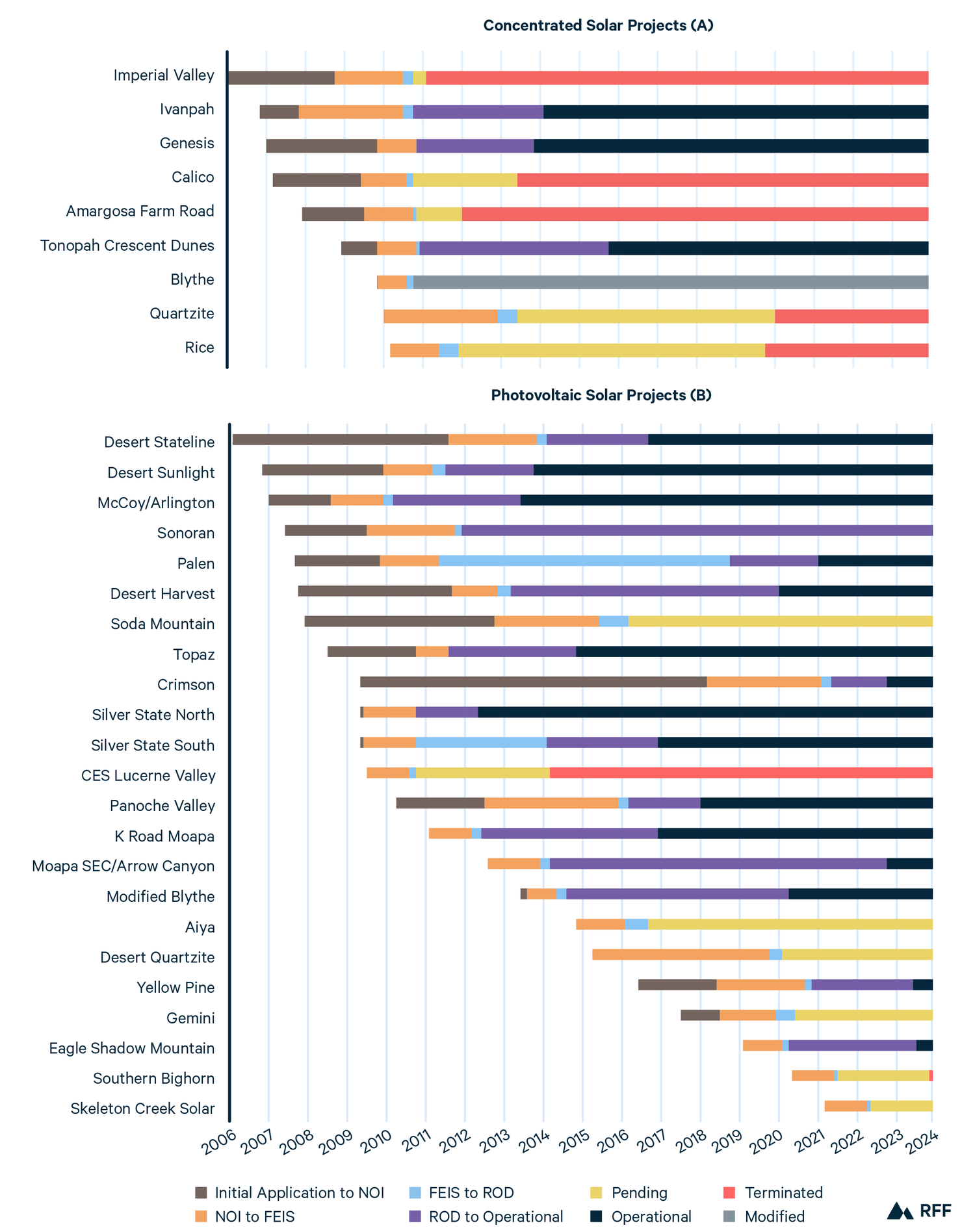

We identified 32 solar projects that completed the EIS process from 2009 to 2023. Modified Blythe solar is an extension of the Blythe solar project. Blythe solar was reviewed under NEPA and awarded a ROW lease as a concentrated solar power project in 2010. The original developers declared bankruptcy in 2011 and NextEra Energy bought the Blythe project assets. NextEra requested BLM approval of a variance to the ROW to allow a change to a PV design and a reduction in the project footprint. BLM completed a FEIS and issued a ROD on August 1, 2014 (BLM 2014a). The Colorado River Indian Tribes challenged the BLM approval of these changes on December 4, 2014 (see Colorado Indian Tribes, et al. v. Department of Interior, et al. 5:14-cv-02504 (D. California 2014), https://www.basinandrangewatch.org/CRIT%20Lawsuit%20Blythe.pdf). We adopted the Blythe–Modified Blythe split as separate projects to reflect the BLM decision to undertake a separate EIS to address NextEra’s proposed revisions to the project and the additional court challenge to the project by the Colorado River Indian Tribes. Of these 32 projects, seven were terminated and one was modified, leaving 24 operational or still pending operation as of December 2023. Three-quarters of the EIS reviews covered solar projects on BLM lands. The remaining projects were completed by various other agencies: Section 404 issues (USACE/Panoche), DOE funding (DOE/Topaz), and siting on tribal lands (BIA). Figures 1a and 1b present the several stages in the development of solar projects: initial application to the federal agency to the NOI (brown), NOI to FEIS (orange), FEIS to ROD (blue), and the final step of ROD to generation (purple). Pending projects extend through the timeline with gray-outlined boxes and terminated projects are extended with red-outlined boxes. Note that BLM has an additional step after the ROD, the notice to proceed (NTP). The NTP step ensures that developers meet requirements in the right-of-way (ROW) governing the construction and operation of these projects before they begin construction (BLM n.d.d).

The average time to complete a formal EIS review and issue a ROD for these 32 solar projects—27 months—is substantially shorter than the average NEPA review time of 4.5 years across all types of projects across all federal agencies (CEQ 2018a). Roughly 70 percent of the projects completed the NEPA process—NOI, formal environmental review, EIS, and ROD—in one to two years (see Appendix A). Eleven projects, however, encountered longer delays in the NEPA EIS review and associated federal permitting processes, for a variety of reasons: for four projects, changes in design and changes in ownership (including bankruptcy) occurred as photovoltaic emerged as the dominant technology; for four projects, environmental and tribal issues raised during NEPA reviews required design changes and reduced their acreage and capacity; and for the remaining three projects, the primary agency’s EIS review process delayed the project. Other delays were related to court challenges to projects based on NEPA or state environmental laws. These court challenges will be covered in a subsequent report.

Although many of the formal NEPA EIS reviews were concluded in less than two years, some projects required a much longer gestation period from initiation to completion. The NEPA review is the filling in a sandwich: it is preceded by application, development, and scoping processes and followed by construction and interconnection to the grid in accordance with the permit conditions. The record suggests that 12 projects in our sample (of 21 for which we have an initial application date) required more than two years from the initial application to the NOI announcement of formal NEPA EIS review; eight projects required less than two years to start formal NEPA review. The start date for these projects included the date developers filed Form 299 as a formal application. Where we were not able to identify a formal application date, we used the earliest date we could identify for federal agency initiation of review, such as letters to interested parties or announcements of public hearings. GSA Standard Form SF 299 is a Government Services Administration form required for applications across federal agencies for transportation, utilities, telecommunication, and facilities access to federal public lands.; The project count includes Blythe and Modified Blythe as separate projects. For projects requiring more than two years, it is likely that addressing various NEPA-related issues contributed to the delay associated with this prequel period of application development.

Figure 1. NEPA Timeline for Processing Utility-Scale Concentrated (A) and Photovoltaic (B) Solar Power Projects

None of the 16 non-terminated projects for which we have complete information reached full operation from the initial action date within five years. This calculation combined the timeline for the Blythe (CSP) and Modified Blythe (PV) projects. Modified Blythe required less than five years from the time NextEra Energy submitted a variance request to convert the ROW grant to allow the use of PV solar technology to reach operational status (BLM 2014). Nine projects took at least seven years, with three of these projects requiring more than 16 years (two were still pending as of December 2023).

After completing formal NEPA EIS review with a ROD, four of the 24 non-terminated projects completed construction and commenced operation in less than two years. However, nine of these 24 projects (including 4 pending projects) required four or more years to reach operational status after completing formal NEPA review.

4.2. Onshore Wind

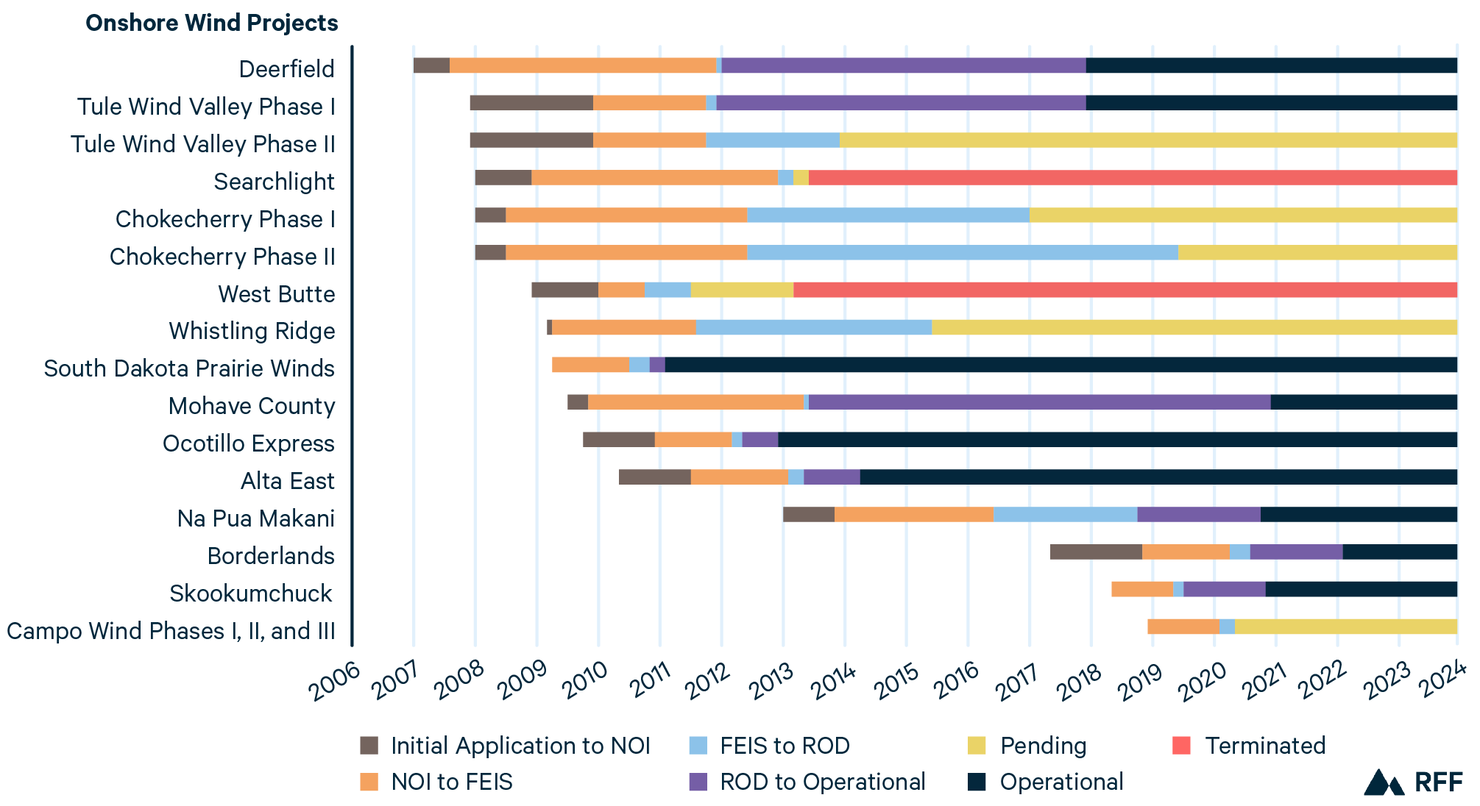

We identified 16 wind projects that completed EISs from 2009 to 2023. 2 projects were terminated, leaving 14 operational or still pending operation as of December 2023. Half of the EIS reviews covered projects on BLM lands. Various other agencies served as primary agencies for the remaining projects: Bureau of Indian Affairs for sites on tribal lands, Fish and Wildlife Service, USDA Rural Utilities Service, Westen Area Power Administration and Bonneville Power Administration.

Figure 2. NEPA Timeline for Processing Onshore Wind Projects

The average time from the NOI initiating a formal EIS review to the ROD for these 16 wind projects, 45 months (3.75 years), is substantially longer than the average review time for solar projects and closer to the NEPA review time across all projects from all federal agencies, 4.5 years (CEQ 2018a). Half of the projects completed the EIS process—from NOI, formal environmental review, and EIS to ROD—in one to two years. For the remaining projects, however, the NEPA EIS review and associated federal permitting processes resulted in longer delays, for a variety of reasons. For five projects, an extended agency review process delayed completion. Two projects encountered an extended agency review process coupled with adverse court decisions.

As discussed above for solar, the overall development process for many of these projects from initiation to completion takes much longer than the formal NEPA review.

All the onshore wind projects for which we have full NEPA timeline information (13 of the 16 projects in our sample) required less than two years from initial action to the NOI announcement of formal NEPA EIS review. This is a much shorter preliminary review period than observed for most of the solar EIS projects. We were not able to locate information on the initial application date for three projects. However, nine of the 14 non-terminated projects, including the pending projects, required two or more years, and seven of these nine required four or more years from the completion of the formal NEPA review to reach operational status. Approximately 16 years have elapsed for three of the five pending projects from the date of their initial action to December 2023.

4.3. Geothermal

We identified only three geothermal projects that completed NEPA EIS reviews within the study period. The bulk of the NEPA reviews for geothermal projects were addressed through the NEPA EA process. Two projects completed NEPA EIS reviews in two years; the third (Casa Diablo IV) completed the review in 29 months. The sample size, and the fact that only one project has reached operational status, limits any additional discussion.

5. Results for Environmental Assessment Reviews

5.1. Utility-Scale Solar

Agencies used the less demanding NEPA EA process for 19 solar projects and typically completed the environmental and cultural reviews with a finding of no significant impact in a substantially shorter time. This includes a prequel period of scoping and review. For these projects, CEQ rules did not require the primary agency to publish a NOI. In some cases the start date for these EA projects includes the date developers filed Form 299 as a formal application. For projects where this information was not available, we used the earliest date we could identify for a federal agency to initiate review—for example, letters to interested parties or announcements of public hearings. The average review time was less than 23 months. Six projects reached a FONSI decision in one year or less; nine completed this process in two years or less; four required more than two years.

In addition, the average time from the completion of FONSI review to operational status for these 19 projects was 36 months (including four projects that were pending as of December 2023); nine reached operational status in two years or less; three required more than four years to complete construction and begin operation.

In addition to those 19 projects, USDA RUS completed EAs in 2022 and 2023 to support loan guarantees for nine solar projects (see Appendix B). Both DOE and more recently USDA RUS used EAs to support their loan guarantee programs. These projects were located on private lands, typically agricultural.

BLM used EAs beginning in 2009 as it initiated its effort to open federal public land to renewable energy projects. BLM used EAs for three solar projects in 2014, with a competitive auction in the Dry Lake solar energy zone (SEZ) under “interim competitive procedures.” The auction served as a pilot project in advance of BLM’s completion of its 2016 competitive leasing rule for solar and wind energy development. Subsequently, BLM also adopted EAs for a limited set of projects sited in “variance” areas. In addition to the designation of SEZs, BLM also designated 19 million acres of its lands as variance areas. Whereas projects proposed for SEZs were given priority status, with reviews tiered off earlier EISs, BLM regulations required a full case-by-case review for proposed projects in variance areas. Within its discretion, BLM completed the required review for some of these variance area projects with an EA.

5.2. Onshore Wind Environmental Assessments

Agencies used the less demanding NEPA EA process for nine wind projects. We did not obtain sufficient information for individual projects to provide the average time from initial action to completion of the environmental and cultural reviews with a FONSI.

The average time from the completion of EA review to reach operational status for eight of the nine projects was 14 months. Five projects (four of which were in Hawaii) reached operational status in one year or less. Two projects took one to two years, and one required more than two years. Summit Wind in South Dakota, the ninth project, received its FONSI in August 2015, and the project is still pending.

5.3. Geothermal Environmental Assessments

BLM used NEPA EAs for the bulk of its reviews of geothermal projects. BLM has authority for leasing geothermal resources on federal public lands and for the subsurface mineral estate, including on National Forest System lands managed by the US Forest Service (an agency of the US Department of Agriculture). BLM manages these energy projects through leases as opposed to ROWs used for solar and wind projects (Nedd 2022). Geothermal projects generally have much smaller footprints than solar and wind facilities. As a result, NEPA evaluation of a project and support for a FONSI were typically less challenging than with solar and wind projects. In April of 2024, BLM adopted categorical exclusions used by the US Forest Service and Department of Navy to hasten geothermal project development (BLM 2024).

We identified start dates for 12 of the 13 EA geothermal projects completing the environmental and cultural reviews with a FONSI. The average review time from start of review to the FONSI for these 12 projects was 14 months. This includes a prequel period of scoping and review. For these projects, CEQ rules did not require the primary agency to publish a NOI. The start date for these EA projects includes, in some cases, the date developers filed Form 299 as a formal application. Where this information was not available, we used the earliest date we could identify from other sources for a federal agency to initiate review—for example, letters to interested parties or announcements of public hearings. Five of the projects completed the process in one year or less; seven took one to two years; one required more than two years.

The average time for the 13 projects from the FONSI to operational status (or still pending in December 2023) was 33 months. Three projects reached operational status in one year or less; four reached operational status within two years. Two projects required more than two years to complete construction and begin operations. Four projects, still pending as of December 2023, had not yet begun operation two years after the FONSI.

5.4. Delays after Completion of NEPA EIS and EA Reviews

Right-of-way permits generally include multiple provisions that developers must meet in constructing and operating the project. Examples of such provisions include bonding requirements to cover reclamation, fire prevention and response planning, erosion control planning, site restoration planning, and revegetation or weed management planning (BLM n.d.d). After the ROW is issued, BLM adds a notice to proceed (NTP) step for large projects (such as utility-scale solar and wind facilities) to ensure that developers meet these provisions (BLM n.d.d). Developers must submit a plan for meeting the requirements before starting construction. After reviewing and approving the plan, BLM issues an NTP, allowing developers to proceed with construction. The NTP process appears to be unique to BLM.

For seven solar projects (of 16 projects for which we have NTP data), BLM issued the NTP within one month. However, within this limited sample, some projects experienced a substantial lag in receiving the NTP: 20 months for Gemini, 38 months for Desert Quartzite, 40 months for Lucerne Valley, and 78 months for Desert Harvest.

For two wind projects (of four projects for which we have NTP data), BLM issued the NTP within one month. The other two projects saw a substantial lag: 59 months for Tule Valley I, and 64 months for Mohave.

Apart from the NTP process, industry studies and press reports indicate that the difficulty in navigating the queue for interconnection has contributed to delays in bringing projects to completion (Skok and Giacobone 2024; Berkeley Lab 2024).

5.5. Missing Data

Most of the federal agencies maintain databases providing information on the main steps in the formal NEPA EIS process, but information on steps prior to the NOI and following completion of the ROD was not readily available. In addition, agencies’ data on the steps in the EA process were even more limited. This section describes the gaps in information on the full development timelines for renewable projects.

As an initial step, BLM’s EIS process requires that developers submit an application, which BLM uses as the basis for determining an application fee. BLM also reviews the application for completeness. When the application is deemed complete, BLM begins a formal NEPA review with publication of a Notice of Intent (NOI) in the Federal Register. CEQ regulations require agencies to issue an NOI in the Federal Register when they initiate a NEPA EIS process. For environmental assessments, CEQ does not require an NOI, and agencies use a variety of less formal approaches to notify interested parties of their review. Although we could not identify a centralized BLM site with information on the date developers filed the initial application, we did find a date for the initial application for most BLM projects.

We were less successful in identifying similar preliminary steps prior to the NOI for other agencies.

In addition, agencies do not typically report the date when they initiate formal NEPA review for EAs—that is, there is no systematic reporting by agencies of the start of a process equivalent to the NOI required for EISs.

For the period covered by this study, CEQ regulations gave primary agencies substantial discretion in notifying interested parties of the intent to develop an EA. There was no requirement to publish a NOI in the Federal Register. As a result, agencies have adopted several alternatives, such as publishing a notice in local newspapers, using other local media, and contacting interested community organizations. In some cases, we found a date for early contact between developers and a government agency based on announcements issued by the developer, news releases from nongovernmental organizations, and outside newspaper and trade press sources. Overall, agencies retain substantial discretion for actions with effects that are primarily of local interest making it difficult to track down start dates for EAs. 40 CFR part 1501.9.

For project terminations, we were not able to locate centralized agency sites reporting the termination of a project. In a few cases, we found an agency site reporting that the developers had given up their lease or permit. Otherwise, we relied on newspaper and trade press articles, news releases from NGO groups, and academic articles.

Finally, BLM does not maintain a centralized database with NTP information on individual projects. We obtained information for a limited set of wind and solar projects from BLM press releases, developer websites, and industry trade press.

To improve transparency and better inform decision-making on the NEPA process, agencies should provide additional information on their review process for individual projects in an accessible database: the date a developer submits an application to the agency, a record of significant agency requests for further information, and the notice on initiating a formal NEPA EA review. In addition, agencies should post information on any NTP step following a ROD or FONSI.

At the outset of this effort, we wanted to join transmission interconnection queue data, published by DOE through the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, with our database to provide interconnection timelines alongside NEPA process timelines. However, we ultimately were not able to make quality matches between the projects in the DOE queue database and the projects in our database. Interconnection queue data entries vary by regional transmission organization (RTO) or independent system operator (ISO). IDs assigned to projects in the queue are unique to the project and RTO or ISO convention. In many cases, the project’s name is not included alongside the ID. Where projects were named and corresponded in location and energy resource type to named projects in our database, we found discrepancies that lowered our confidence in the quality of matches. Examples of these discrepancies include queue entry dates prior to the initial action date of the project, queue statuses not indicating interconnection for projects that were known to be operational, and differences in reported megawattage. One simple solution would be to present project names alongside IDs for all ISO or RTOs. Six out of the 51 ISOs/RTOs in the interconnection database as of the end of 2023 publish project names for all queue entries (Rand et al. 2024).

Future research could reconcile these discrepancies so that the interconnection data can be linked with the NEPA review timelines to provide a better understanding of the effect of the interconnection and NEPA processes in delaying these projects.

6. Conclusion

Although federal permitting is often discussed as a critical obstacle for building energy infrastructure, NEPA review for renewable energy projects was generally more expeditious than for other major infrastructure projects. Solar and wind projects completed the NEPA environmental impact statement process more quickly than the average completion time across all project types across all federal agencies. Compared with the CEQ average of 54 months, solar and wind projects required 27 and 45 months, respectively, to complete the NEPA EIS process (CEQ 2020). Of these solar and wind projects, 62 percent completed a formal NEPA EIS process within one to two years. However, average review time is skewed by the minority of projects that took substantially longer: one-third of the solar projects and half of the wind projects exceeded the Fiscal Responsibility Act’s two-year deadline for completing a formal EIS review. Projects exceeding the FRA’s 2 year deadline likely account for a disproportionate share of the policy conversation about problematic NEPA delays in clean energy development, but it is also possible that the risk of a prolonged NEPA process has dissuaded developers from building on federal land. In any event, the solar and wind projects reviewed under the National Environmental Policy Act account for only a small fraction of the increase in installed renewable capacity over the 2010 to 2023 period (EIA 2024).

In analyzing the time from initial action to date of operation, we observe evidence of other significant sources of delay for project developers. For the subset of 16 solar projects completing EIS review for which we have complete information, none were able to complete construction and commence operation in less than five years from the date of application. Four of these projects required more than eight years to reach operational status. Three of the ten wind projects for which we have information were able to go from initial action to operation within five years; four wind projects required more than eight years.

We also find significant delays for a number of projects after the conclusion of formal NEPA review. Eleven of 24 solar projects, six of 14 wind projects, and all three geothermal projects required more than four years to complete construction and begin operation. We sought to combine data for these projects with interconnection queue data to identify whether that process played a significant role in their delay, but a lack of consistency in project identification across data sources thwarted our efforts.

On average, NEPA environmental assessments are completed in less time than environmental impact statements. The projects undergoing EA review have limited environmental consequences, so the EAs are less complicated. However, 13 of 19 solar projects and eight of 12 geothermal projects required more than one year—the timeframe established in the recent FRA –to reach a finding of no significant impact from their initial action dates. Despite the uncertainty in the initial action dates, it seems likely that agencies will find it challenging to comply with the one-year time limit for review established in the Fiscal Responsibility Act.

As Congress considers further reforms to NEPA, this paper provides a historical perspective on how NEPA reviews affect renewable energy projects. NEPA review is just one of many factors that affect timelines. Financial problems faced by developers, for example, were a contributor to post-review delays. Further research into the hurdles delaying the deployment of renewable energy projects requires more information on the circumstances causing delays both before and after formal NEPA reviews. This effort should include developing systematic reporting the various aspects contributing to delay and, in some cases, termination of these projects before and after completion of formal NEPA review.