Taking Green Energy Projects to Court: NEPA Review and Court Challenges to Renewable Energy

This report examines the impact of litigation on utility-scale wind and solar energy projects undergoing NEPA review.

Read the related NEPA’s effect on renewable energy projects report.

Read the associated press release.

Abstract

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is often identified as a major obstacle to renewable energy projects locating on federal public lands or seeking federal funding. Once NEPA permits have been issued, a project may face additional delays if a federal agency’s decision is challenged in court. The delays associated with NEPA permitting for renewable generation projects have been explored by Fraas et al. (2023, 2025), but the effect of environmental court challenges to renewables projects has received less attention. This paper builds on Fraas et al. (2023, 2025), examining the legal challenges faced by each project and presenting the timeline in months for each case. Nearly a third of solar projects and half of wind projects completing NEPA environmental impact statement reviews faced court challenges. Almost all cases were filed after the government agencies had issued their permitting decisions. Although the courts typically ruled in the government agencies’ and project developers’ favor, the majority of cases were appealed. Court challenges in both federal and state courts caused or contributed to the termination of three projects, and six additional projects experienced significant delays as developers awaited court appeal decisions.

1. Introduction

Renewable energy projects are at the core of efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity sector, but developers have long expressed frustration with the myriad obstacles to building new generation projects. Beginning with the 2005 Energy Policy Act (EPAct), the federal government has sought to open federal public lands to renewable energy projects. However, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires federal agencies to assess the environmental effects of proposed major federal actions prior to making decisions such as approving a lease for infrastructure projects built on federal lands or providing financing for these projects.

Federal lawmakers have been exploring adjustments to NEPA reviews to make them more expeditious and encourage development on federal lands. Those adjustments include restricting what qualifies as a “federal action” subject to NEPA, expanding categorical exclusions, narrowing the set of actions that require an environmental impact statement (EIS), imposing shorter deadlines for EIS and environmental assessment (EA) compilation and review, and imposing a strict statute of limitations on NEPA-related litigation. But the trade-offs associated with such reforms are unclear when it comes to renewable energy projects. Fraas et al. (2023, 2025) find that renewables projects move through NEPA review more quickly than the average project in the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) database, and that much of the project development timeline occurs outside the formal NEPA process.

Some critics of NEPA have pointed to litigation as an important additional barrier beyond the administrative and public-facing processes associated with NEPA (Chiappa et al. 2024; Rutzick 2018). However, there is limited information on the effect of litigation on infrastructure projects. This paper builds on previous work from Fraas et al. (2023, 2025), who cataloged the various utility-scale renewable projects that completed the NEPA process over the period 2009 to 2023. We use a definition of utility-scale projects as projects with a capacity greater than 20 megawatts (AC). FERC has adopted 20 megawatts as the cut-off for large merchant generators. Projects with a capacity greater than 20 megawatts would generally compete in the wholesale power markets (NARUC and USAID n.d.; Urban Grid 2019). In this report, we examine the legal challenges facing each project and present the timeline for each case. Nearly a third of solar projects and half of wind projects completing NEPA EIS review faced court challenges. In nearly every instance, these cases were filed after the government agencies had issued their decision. The defendants—government agencies and project developers—prevailed in most cases. However, court challenges caused or contributed to the termination of three projects, and six additional projects experienced significant delays as developers waited for final court approval. Ultimately, we find that wind and solar projects that faced court challenges have similar development timelines to wind and solar projects without court challenges when considering both operational projects and projects still pending operation as of December 2023.

2. Takeaways

Takeaway 1: We identified court cases raising NEPA-related concerns (or similar violations of state or local requirements) for the following:

- 12 solar projects (of 32) that completed EISs and two projects (of 19) that completed EAs.

- Eight wind projects (of 16) that completed EISs and one project (of nine) that completed an EA.

- One geothermal project (of three) that completed an EIS; no lawsuits were filed for geothermal projects that completed EAs.

Takeaway 2: Regional or local environmental groups and Tribal representatives were the largest source of court challenges to solar and wind projects. National environmental groups filed court challenges for five solar projects (of 14) and one wind project (of 9). The court cases also typically listed individuals as plaintiffs to establish standing. BLM was the primary defendant in a majority of the federal cases. In the state court cases, the defendants were state or local agencies responsible for permitting the projects.

Takeaway 3: A preponderance of these court challenges were filed in federal courts. Cases were filed for some projects in both state and federal courts; three projects faced a challenge only in the state courts. Typically, plaintiffs filed cases after federal, state, or local agencies issued a decision on a project. For cases brought in federal court, the initial filing for 10 of 27 cases was made within 60 days of the date the federal agency issued the record of decision (ROD) or other critical decision and within 120 days for 22 of 27 cases. Typically, defendants in both the federal and the state cases included individuals from the agencies and the project developers.

Takeaway 4: In federal courts, the grounds for the challenges were based on violation of NEPA and multiple other federal statutes. In the state courts, the challenges were based on violations of state environmental statutes (e.g., state-level environmental policy acts) and state or local zoning and planning requirements.

Takeaway 5: Defendants prevailed in most cases, but a few court cases caused or contributed to the termination of three projects. Six additional projects experienced significant delays as developers waited for final court approval.

Takeaway 6: All the court challenges filed contesting NEPA reviews by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) addressed the Obama administration’s “Fast Track” candidates. No court cases challenging BLM’s NEPA reviews were filed after January 2014.

Takeaway 7: Only three (of 41) court cases challenged renewables projects that had completed EAs. The 41 total comprises 19 solar projects, nine wind projects, and 13 geothermal projects.

3. Background

Two recent studies—Adelman and Glickman (2017) and Ruple and Race (2020)—assembled data on NEPA court cases for all NEPA decisions (categorical exclusions, Categorical exclusions are categories of actions that do not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human environment (CEQ 2018; 18 CFR § 380.4–5). EAs, Environmental assessments provide a scoping process to determine whether a project may have a significant adverse environmental effect. The EA process is completed when the agency either issues a finding of no significant impact (FONSI) or reaches the conclusion that an EIS is required (BLM n.d). and EISs) for all types of projects across all agencies covering the period from 2001 to the mid-2010s. Both studies concluded that overall, few NEPA decisions were challenged in court (one litigation case per 450 NEPA reviews), but that conclusion rested on the total number of NEPA decisions, roughly 100,000 per year, including the large volume of categorical exclusions. Both studies recognized that EISs constituted a small fraction of the total NEPA decisions in their samples. Ruple and Race (2020) report that EISs accounted for less than 1 percent of the federal actions in their sample, for example.

Although NEPA EIS reviews account for only a small fraction of total NEPA actions, they account for a major fraction of NEPA court challenges. Bennon and Wilson (2023) present data on court challenges to EISs completed from 2010 to mid-2018, Bennon and Wilson (2023) report that 7 percent of their sample involved another federal statute (but not NEPA), and 4 percent involved state environmental statutes. focusing on subsectors of the energy and transportation sectors. They report that utility-scale solar projects had a litigation rate of 64 percent, the highest rate of litigation across the 38 energy and transportation subsectors covered by their study. Pump storage had the highest rate, at 100 percent, but there was only one project in the Bennon and Wilson (2023) data set. Wind projects had a litigation rate of 38 percent at the high end of litigation rates across the 38 subsectors.

Ruple and Race (2020) report an inverse relationship between the time required to complete EIS review and the litigation rate. Bennon and Wilson (2023) suggest there may be an incentive for developers facing substantial private financing requirements—for example, utility-scale energy-related projects like solar and wind—to accept a higher degree of litigation risk rather than spend time working through an extended NEPA process. As opposed, for example, to transportation projects that are largely funded by the federal and state governments (Bennon and Wilson 2023). This conjecture points to the potential trade-off between a longer agency review process, including the application review process prior to formal NEPA review that allows negotiation with interested groups, and a higher risk of litigation after agencies have completed an “expedited” NEPA process.

4. Methodology

We used the renewable energy projects identified in Fraas et al. (2025) as the basis for this work. The projects we assessed were limited to generation facilities subject to formal NEPA review. We used LexisNexis, Westlaw, and Google to locate relevant court cases addressing the range of issues typically associated with NEPA litigation. On LexisNexis and Westlaw, we conducted general searches using the project name and identified litigation with similar names occurring within the same timeframe and geographic region as the project. We excluded cases filed after the operational date of the project. Google served as a secondary check to ensure that no relevant cases were missed. Because LexisNexis is not available to the general public, we also used Google to search secondary sources—various federal and state agency sources, newspaper and trade press articles, and publications from NGO groups—for several cases. Sites run by plaintiffs’ organizations, such as Friends of the Columbia Gorge and Basin and Range Watch, aided in identifying case decision dates. In addition, Bennon and Wilson (2023) generously shared their spreadsheet identifying projects subject to NEPA and state environmental lawsuits. Only projects that underwent federal NEPA review or similar State level review of the powerplant were included. This restriction excludes projects like California’s North Sky Wind River Energy Project, which underwent federal NEPA review only for its interconnection infrastructure (Chiappa and McCarthy 2024).

In our summaries of the cases filed for individual projects (Appendix 2), we present the basic outlines of the cases—plaintiff organizations, government defendants, statutory basis, initial filing date, and dates of court decisions. We have not captured the full details of each case, such as various motions and filings. We provide citations for sources by project in a supplemental document.

4.1. Missing Data

LexisNexis and Westlaw are not complete or comprehensive sources of case law. In addition, as mentioned above, LexisNexis and Westlaw are available to the general public only through a paywall. As a result, we faced challenges in finding other sources as substitutes for these two key sources. While we were generally able to find the decisions of the federal appeals courts, we were less successful in locating US district court opinions. Information on state court decisions presented an even greater challenge, and we often had to rely on secondary sources for basic information.

5. BLM and Fast-Track Court Challenges

At the end of 2009, BLM had more than 200 active applications for renewable energy projects on BLM lands, including 128 solar projects and 24 wind projects. To manage this caseload, the Department of the Interior (DOI) and the Department of Energy (DOE) launched a fast-track initiative: Congress extended the eligibility deadline for loan guarantees for renewables projects to September 30, 2011, to allow additional projects to qualify for loan guarantees. Eligible projects were required to start construction by September 30, 2011 (Brown 2011; Governmental Accountability Office 2012).

To further make our goals a reality, we have announced 34 “fast track” renewable energy projects. Fast-track projects are those where the companies involved have made sufficient progress in the environmental review and permitting process that they could potentially be cleared for approval by December 2010, thus making them eligible for economic stimulus funding under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 (DOI 2010).

In early 2010, DOI identified 14 solar, seven wind, and three geothermal projects as fast-track candidates undergoing environmental review (Sustainable Business 2010).

Between the fall of 2010 and mid-2011, BLM completed NEPA EIS and EA reviews for 15 solar projects—most were fast-track candidates. Many of these projects were able to start construction before the September 30, 2011, deadline and therefore were eligible for ARRA loan guarantees.

In response to BLM’s “greenlighting” of these projects, plaintiffs filed cases challenging 10 solar and three wind fast-track projects. In these early cases, plaintiffs specifically cited their concern that the fast-track process resulted in inadequate EISs and inadequate government-to-government consultation with the tribes and other interested parties. A spokesperson for La Cuna de Aztlan Sacred Sites Protection Circle—a major plaintiff in challenging solar projects—explained: “...the pressure of the ARRA “fast track” process approved by Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar resulted in inadequate Environmental Impact Statements and inadequate government-to-government consultation with the tribes and native groups” (Salem News 2011). The grounds for the challenges in federal courts were based on the alleged violation of NEPA and a variety of federal statutes. In the state courts, the challenges were based on violations of state environmental statutes (e.g., state-level environmental policy) and state or local zoning and planning requirements.

Federal and State Statutes

There are several federal statutes that provided grounds for the court challenges. They include the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), Endangered Species Act (ESA), Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (BGEPA), Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA), National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), Administrative Procedure Act (APA), Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), and Native American Graves Protection Act (NAGRPA). State environmental policies that were used as grounds in challenges are the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and the California Endangered Species Act (CESA).

Across these fast-track court cases, defendants prevailed in most cases. Plaintiffs prevailed in halting one wind project (Searchlight) and secured a temporary restraining order for a solar project (Imperial Valley). Court challenges also caused or contributed to the termination of the Calico solar project. Plaintiffs also reached a settlement agreement with the California Valley solar project.

However, after this batch of fast-track lawsuits, we have not identified any lawsuits initiated after early 2014 that challenged BLM NEPA decisions. From early 2014 to the end of 2023, BLM completed six solar and one wind EISs and 10 solar and five geothermal EAs. On the other hand, lawsuits have been filed against two solar projects and several wind farm projects challenging decisions by other (non-BLM) federal and state agencies.

Several reasons could explain the lack of BLM lawsuits after 2014. One is the low success rate for plaintiffs: the courts largely ruled in favor of BLM and the project developers. As a result, local or regional groups and the tribes may have concluded that they would get better outcomes by negotiating with BLM and the developers within the NEPA process rather than by going to court. It is worth noting that the national environmental groups reported negotiating settlement agreements—without filing a formal court challenge—and supported some of the early large-scale solar projects that were subsequently approved by BLM in California (Defenders of Wildlife 2012). BLM and the developers may also have learned that careful attention to local or regional groups and tribes in the NEPA process would help them avoid getting tangled up in post-NEPA court cases. Finally, BLM and the developers may also have become more selective in choosing sites by avoiding sensitive habitat and cultural areas.

6. Court Challenges to Solar Projects

We identified 22 separate court challenges to 12 of the 32 utility-scale solar projects that had completed NEPA EIS review. Modified Blythe Solar is an extension of the Blythe Solar project. Blythe Solar was reviewed under NEPA and awarded a right-of-way (ROW) lease as a concentrated solar power (CSP) project in 2010. The original developers declared bankruptcy in 2011, and NextEra Energy bought the Blythe project assets. NextEra requested BLM approval of a variance to the ROW to allow a change to a photovoltaic (PV) design and a reduction in the project footprint. BLM completed a final environmental impact assessment (FEIS) and issued a ROD on August 1, 2014 (BLM 2014). The Colorado River Indian Tribes challenged BLM’s approval of these changes to the project on December 4, 2014 (see Colorado RiverIndian Tribes, et al. v. Department of Interior, et al. 5:14-cv-02504 (D. California 2014), https://www.basinandrangewatch.org/CRIT%20Lawsuit%20Blythe.pdf). We adopted the Blythe–Modified Blythe split as separate projects to reflect BLM’s decision to undertake a separate EIS to address NextEra’s proposed revisions to the project and the additional court challenge to the project by the Colorado River Indian Tribes. These challenges were filed in both federal courts for violations of NEPA and state courts for violations of state and local requirements. In addition, two projects that had completed EAs with a finding of no significant impact (FONSI) were challenged in state courts over state or local agency violations by state or local requirements.

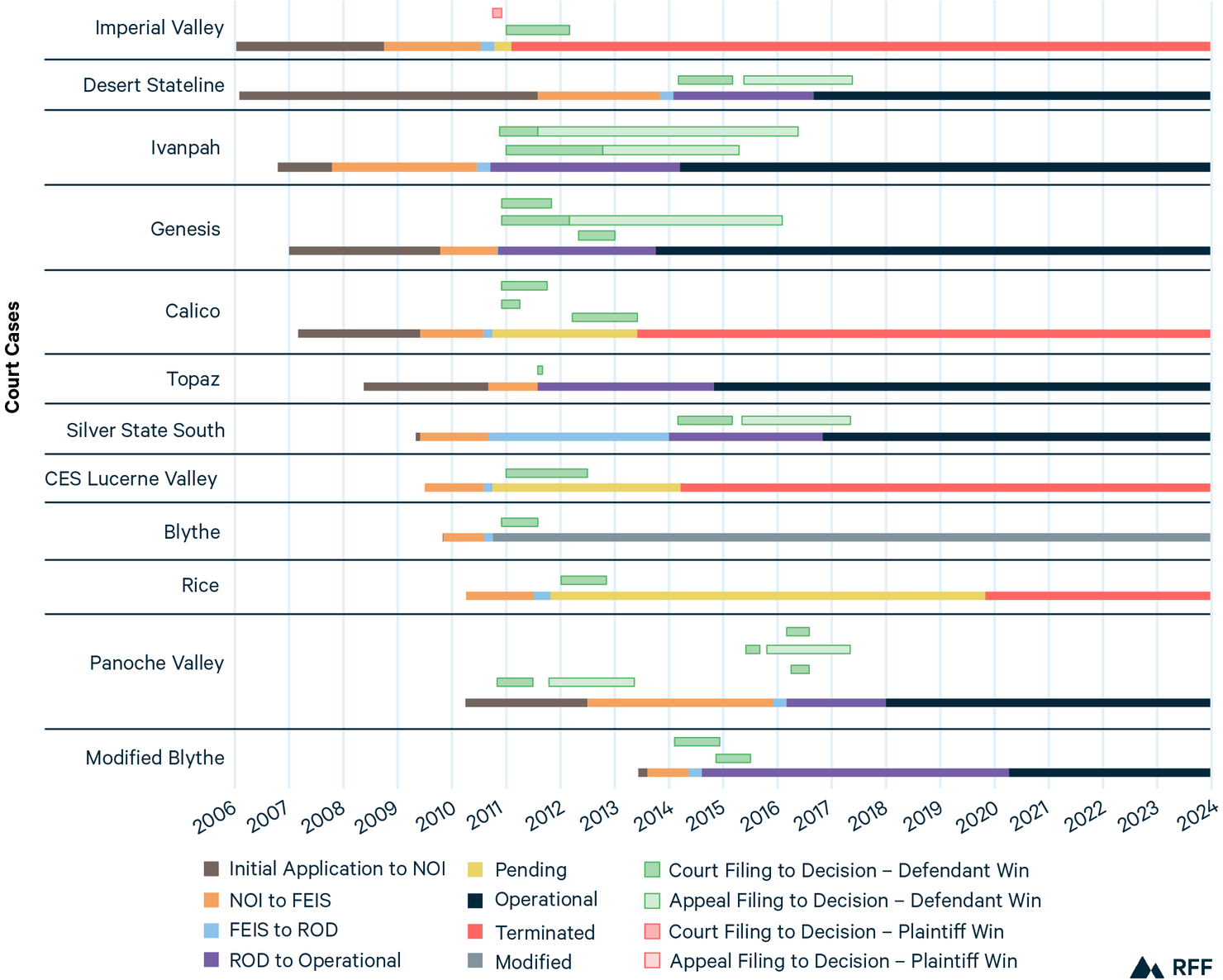

Figure 1 displays the timelines and outcomes of court cases filed against solar projects in relation to their progress through the NEPA EIS permitting process. Cases decided in favor of the defendants or dismissed have their duration shaded light green, and cases decided in favor of the plaintiffs are red. Initial court decisions have a horizontal pattern fill. Appeal decisions have a leftward diagonal pattern fill . The figure shows that many of the cases were filed within a few months of the ROD (green in the NEPA review timeline). A case was filed prior to a final EIS decision in only one instance. Cases filed in the district courts were generally handled within a year; however, cases appealed to higher courts typically required about two or more years before a decision was reached. In the most recent instance, the case was filed in the state courts by neighbors to the Coggon Solar project.

Regional or local environmental groups and tribes (and their representatives) filed 13 (of 22) cases challenging nine of the 12 solar projects that had completed EIS reviews and one of the two cases filed against two solar projects that had completed EA reviews. A showing that one or more of the plaintiffs will be harmed by the challenged action—that is, establishing “standing”—is a critical hurdle in obtaining court consideration of a lawsuit. As a result, the plaintiffs also include individuals who can show that they will be affected by the project. National environmental groups joined local environmental groups in filings for five additional cases. In addition, national environmental groups filed four additional cases as solo challengers for three projects. BLM was the primary federal agency defendant for 10 of the 12 EIS solar projects; US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) were the primary defendants for Panoche Valley. Most of the cases were filed at the end of 2010 and early 2011, shortly after BLM announced its approval of its fast-track projects.

Figure 1. Timeline of Court Cases Filed against Solar Projects Completing EIS Review

Note: For abbreviations definitions, please refer to the abbreviations list at the start of this report.

Defendants for the 12 EIS solar projects prevailed officially in 18 of 22 cases. Cases were dismissed or settled in three other cases. Four of the 12 EIS projects completed construction and began operation before the appeals courts issued a final decision with a finding for the defendants. Four of the projects were terminated. As discussed further below, court challenges caused or contributed to the termination of two projects. Another two were terminated for reasons unrelated to court challenges. Rice was terminated by the developer for economic reasons (Roth 2014). Chevron Energy Systems Lucerne Valley was never constructed because the developer was unable to obtain a permit from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (California State Lands Commission 2021).

Plaintiffs prevailed in securing a court-ordered delay (a temporary restraining order) in one case filed in the federal court system against the Imperial Valley project (Quechan Tribe v. Imperial Valley). Quechan Tribe of Fort Yuma Indian Reservation v. United States Dept. of Interior, 755 F. Supp. 2d 1104 (S.D. Cal. 2010). https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/6005966/129/quechan-tribe-of-the-fort-yuma-indian-reservation-v-united-states/. In February 2011, the tribe announced its intention to seek permanent injunctive relief (Basin and Range Watch 2011). The original developers sold the assets a few weeks later (Prior 2011). AES Solar subsequently shifted the project to nearby agricultural lands and renamed it Mount Signal Solar. This change in location obviated the issues associated with the location of the project on BLM lands (Basin and Range Watch 2011). See the Imperial Valley location: https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/migrated/news/pressreleases/upload/map_Imperial-Valley-Solar-Location.pdf. See the Mount Signal Solar location: https://imperial.granicus.com/MetaViewer.php?view_id=2&clip_id=261&meta_id=30706.

In the case of Calico Solar, the plaintiffs filed suit after BLM announced in October 2011 that it was preparing a supplementary EIS to review K-Road Solar’s request to use photovoltaic (PV) technology in place of the previously approved thermal technology. The US district court suspended the case to allow the developer to provide additional environmental analysis and a revised plan of development. The case was terminated when the developer terminated the project, citing changed market conditions (SI Staff 2013; Sexton 2013). Other sources indicate that the continuing opposition from environmental groups contributed to the decision (O’Shea 2013; Pierce and Steel 2016).

In the case of Panoche Valley, the developer reached a settlement agreement with Defenders of Wildlife, Sierra Club, and Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society to reduce the size of the project before the environmental groups appealed a US district court decision. Reportedly, the company signed the agreement because the environmental groups were continuing to pursue cases they could appeal—including the US district court case—that could result in further delay or even an adverse decision on appeal that would kill the project entirely (Defenders of Wildlife 2013; Hansen 2017).

One of the EA solar projects facing court challenges experienced significant delays. The Coggon Solar project has been delayed several years with a case filed by neighbor that has worked its way through the state court system. As of April 2025, the case was proceeding before the Iowa Supreme Court (Iowa Judicial Branch 2025).

Finally, the developers of the Topaz and California Valley solar farms reached settlement agreements with local environmental groups after they filed in the state courts, The developers of both of these projects agreed to term limits on the use of the sites, to conduct enhanced communication and collaboration on monitoring and mitigation during construction, and to support funding of research on endangered species. (Market screener 2011; SunPower Corp. 2011). In addition, the Topaz and California Valley developers also reached separate agreements with the Sierra Club, Defenders of Wildlife, and Center for Biological Diversity, committing to set aside land for wildlife protection to avoid additional court filings while working to secure permits for the project (First Solar 2011).

Appendix 1 provides additional information on the court challenges to solar projects.

7. Court Challenges to Wind Projects

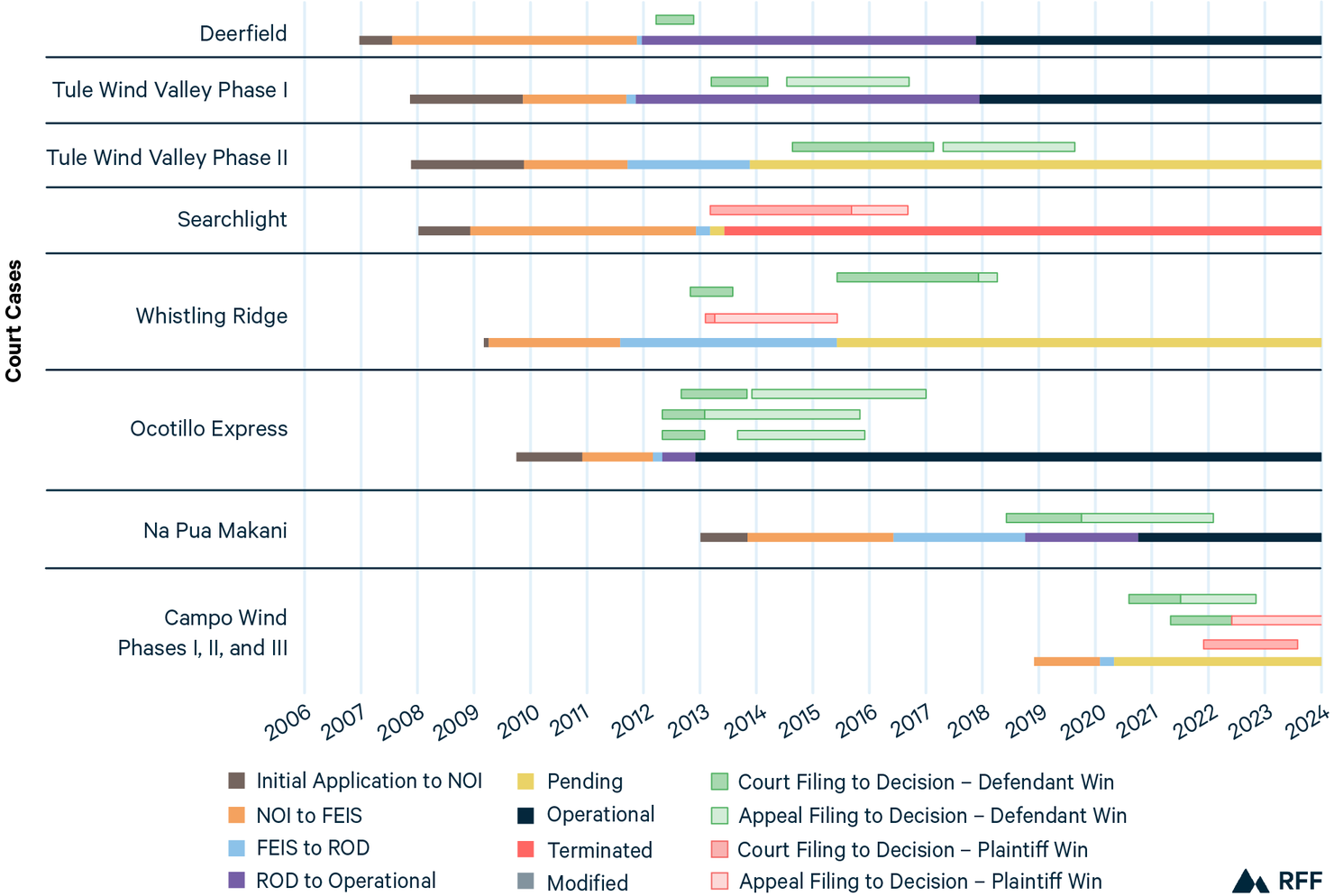

We identified court challenges to eight of the 16 utility-scale wind projects that had completed NEPA EIS reviews in our sample, and a court challenge one of 19 projects that had completed an EA. Six of the nine projects were challenged in federal courts. Two projects were challenged in both federal and state courts, and one was challenged only in the state court system. Figure 2 displays the timelines and outcomes of court cases filed against wind projects in relation to their progress through the NEPA EIS permitting process.

For all nine projects, the court challenges were filed after federal or state agencies had made final decisions approving the projects. Most of the wind cases were filed shortly after federal agencies had completed EIS reviews. Cases challenging Whistling Ridge and Campo Wind were filed after state decisions—and ahead of the federal agency EIS decision.

Figure 2. Timeline of Court Cases Filed against Wind Projects Completing EIS Review

Note: For abbreviations definitions, please refer to the abbreviations list at the start of this report.

Regional or local environmental groups were the plaintiffs in 14 of the 15 cases challenging wind projects; a national environmental group joined regional or local groups in one of the 14 cases. In the 13th case, the Quechan Tribe challenged BLM’s decision for the Ocotillo Wind project. The defendants in the federal cases were the developers and the various federal agencies that had approved the projects. The defendants in the state court cases were state or local agencies responsible for permitting the projects, along with the developers.

Defendants prevailed in nine of the 11 cases filed in the federal court system. The two exceptions were the Searchlight project and the Campo Wind project. For Searchlight, the federal district court remanded BLM’s decision and required it to redo the ROD, FEIS, and biological opinion (BiOp). For Campo Wind, the Ninth Circuit remanded the Federal Aviation Administration’s decision of no aviation hazard on procedural grounds. Plaintiffs also prevailed in two of the four cases filed in state court systems. For the Whistling Ridge and Campo Wind projects the state appeals courts overturned the trial courts’ procedural decisions and returned the cases to the trial courts for rehearing.

Court challenges to two projects, Searchlight Wind and Whistling Ridge, played a major role in their termination. Whistling Ridge was terminated in July 2024 and therefore still appears as pending in Figure 2. The court challenges to Campo Wind have caused a significant delay as the developers await pending court decisions.

8. Court Challenges to Geothermal Projects

Two cases were filed challenging the Casa Diablo IV geothermal project. One case was filed by a labor organization, which challenged air emissions limits in the state environmental permit; the other was filed by the regional water district over concerns that the project would contaminate or deplete the area’s groundwater. The appeal court’s decision in the first case required the district to revoke its 2014 certification of the project and prepare a supplemental environmental impact report to support a revised permit (ESA 2021). Russel Covington et al. v. Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District and Orni 50 LLC, CV140075 Super Ct. No. (2010). https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/geothermalplant.pdf. The total time required to reach a final court decision combined with a reworking of the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District permit delayed the project for about seven years. In the second case, the developer reached a settlement agreement with the regional water district (Mammoth Community Water District and Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District 2018).

9. Analysis of Court Timelines

Litigation associated with the NEPA process is often cited as a major barrier to energy infrastructure projects. Even though nearly a third of solar projects and half of wind projects completing NEPA EIS review faced court challenges, the government agencies and project developers prevailed in most cases. District court cases were typically resolved in roughly a year; when plaintiffs appealed a district court decision, the appeal court case typically extended court review by at least two more years.

Experience with the fast-track projects shows that expedited review processes can lead to increased litigation, particularly for the first projects to take advantage of a newly accelerated process. This suggests that efforts to shorten the formal NEPA review process to speed infrastructure deployment may have an unintended consequence of increasing litigation risk.

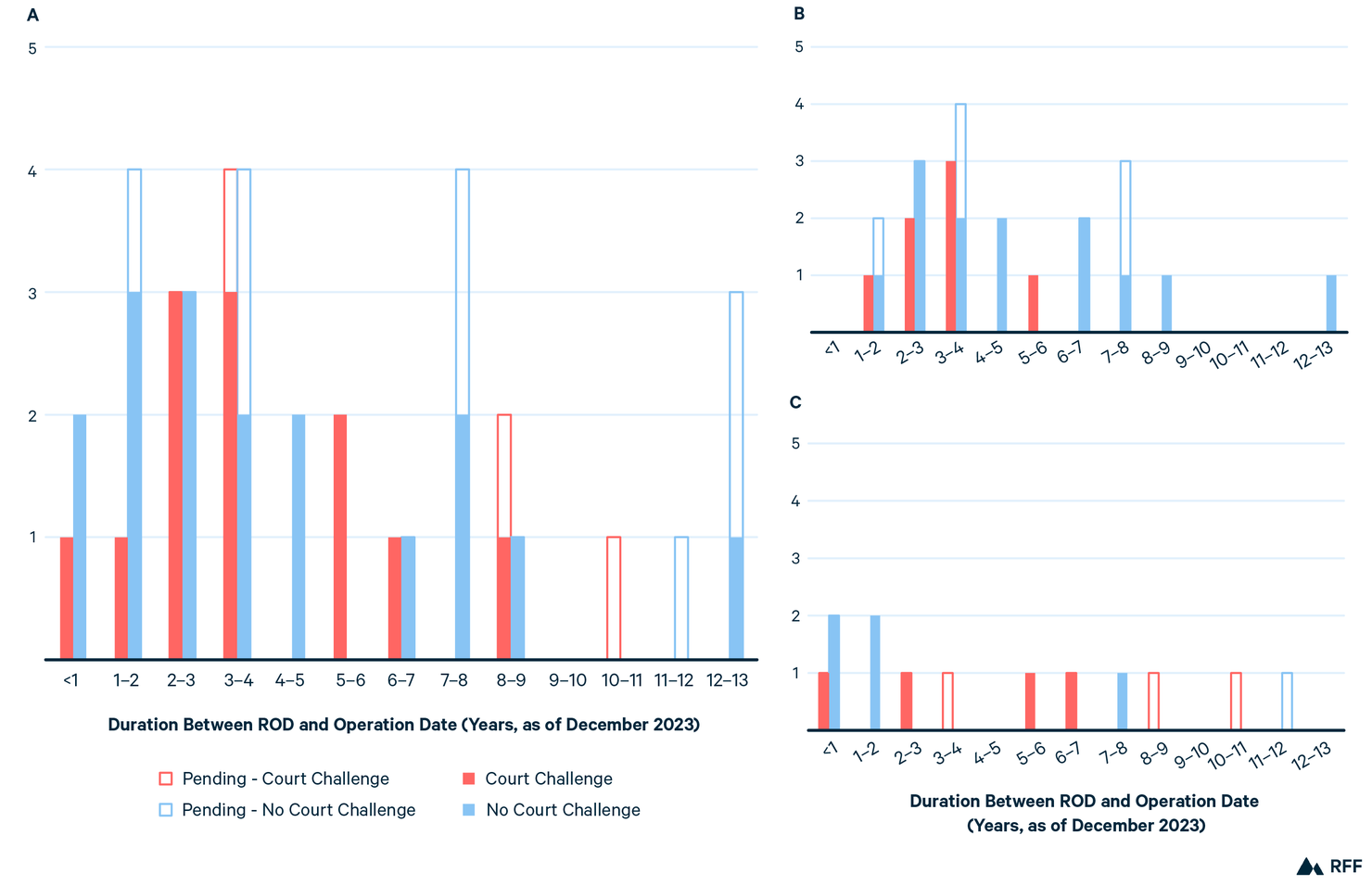

Our sample was too small to allow a meaningful statistical analysis of the effect of litigation on project delay and termination. Figure 3 Panel A presents the distribution of the time required to reach operational status after projects received a ROD. Projects are categorized as either having faced court challenges (solid red bar for operational projects and empty red bar for pending projects) or having avoided a court challenge (solid blue bar for operational projects and empty blue bar for pending projects). The average time for renewable projects to reach operational status is about the same for wind and solar projects with court challenges (41.2 months) than for those avoiding a challenge (40.9 months). Including pending projects lengthens the disparity to about 0.5 months. Panel B of Figure 3 breaks out the distribution of the time to reach operational status for solar projects, and Panel C of Figure 3 breaks out the distribution for wind projects. The difference in average development timelines between projects that were challenged in court and those that were not challenged in court is about 16 months. Unchallenged solar projects were found to take longer than challenged solar projects, at a similar interval of 15 months. Including pending projects increases for difference for solar to about 16 months (there are no pending solar projects that faced a court challenge). When including pending projects for wind the difference increases to about 18 months, though the overall average time elapsed since ROD issuance increases by over a year and a half.

Figure 3. Time from ROD to Current Status for All Cases (A), Solar Projects (B), and Wind Projects (C), by Court Challenge Status

Note: There is one operational, challenged geothermal project in the 8–9 year range, and two pending, unchallenged geothermal projects in the 12–13 year range. For abbreviations definitions, please refer to the abbreviations list at the start of this report.

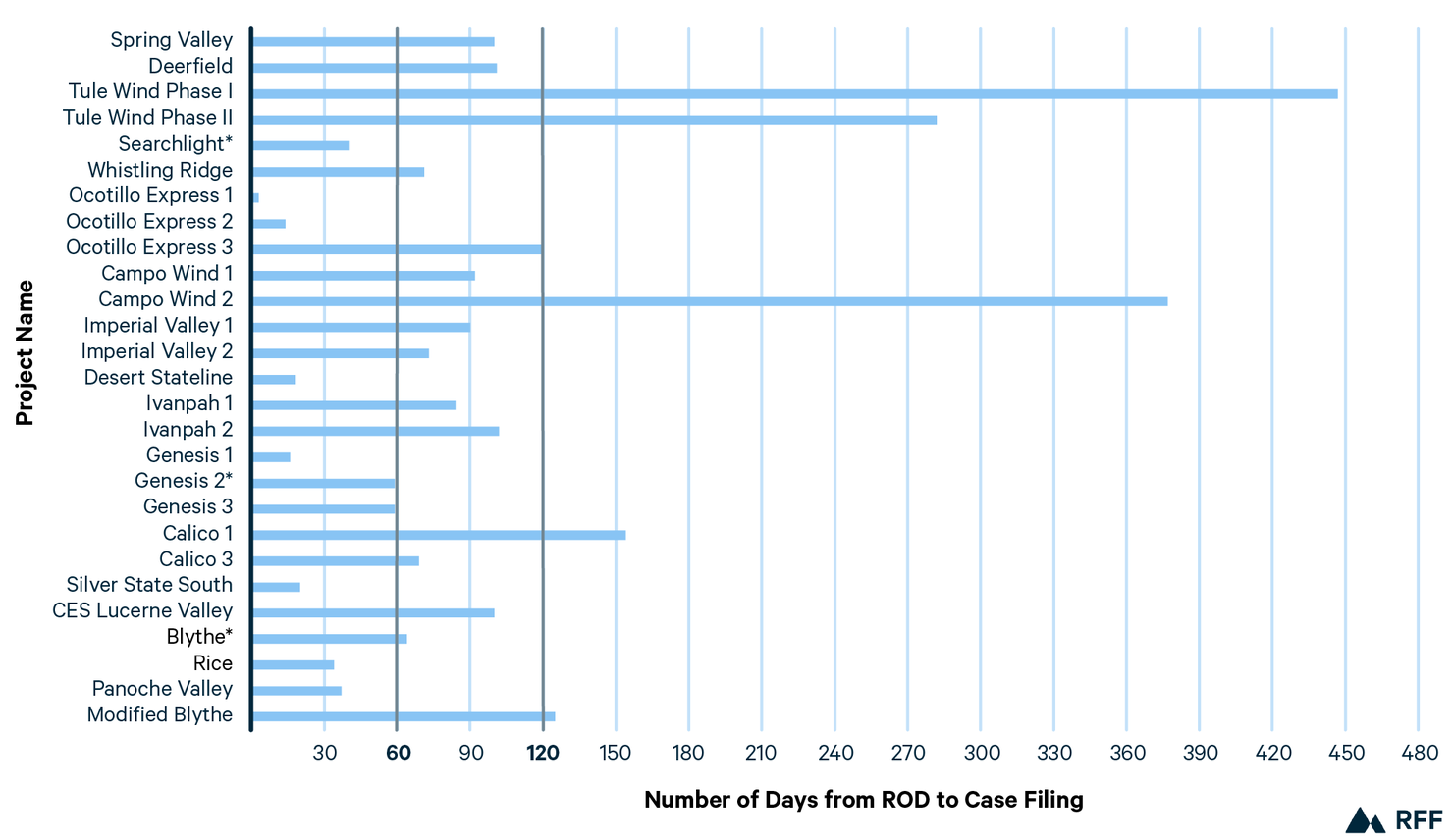

Reform of the litigation process is one focus in the ongoing discussions of permitting reform. The Energy Permitting Reform Act of 2024, proposed by Senators Manchin and Barrasso, included several provisions to limit judicial review. One proposal would have limited the filing period under the statute of limitations for energy-related projects to five months (instead of six years) (US Senate 2024). Other proposals introduced in the last Congress would have reduced the statute of limitations for judicial review to 120 days (separate bills introduced by Representatives Graves and Westerman) and 60 days (introduced by Senator Capito) (US House 2024; US Senate 2023).

Figure 6 presents the time from a federal agency’s ROD (or other critical decision) to the initial filing date for cases brought in federal court. Nearly all federal cases were brought within 180 days of a ROD or other federal agency decision. Ten cases were initiated within 60 days of a ROD while another 12 were initiated between 60 to 120 days. This suggests that future plaintiffs would likely be able to comply with a stringent 120-day statute of limitation. All these filings were initiated within two years, the statute of limitations adopted in the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act of 2015 and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (Fishman et al. 2023).

Figure 4. Time from ROD to Court Case Filing Duration

*Only the filing month is known. The duration assumes the greatest possible number of days from ROD to filing based on the month.

Note: For abbreviations definitions, please refer to the abbreviations list at the start of this report.

10. Conclusion

As Congress considers further reforms to NEPA, this paper provides information on renewable energy projects’ experience with judicial review of NEPA decisions. Federal agencies generally prevailed in NEPA cases; however, court challenges at the federal level caused or contributed to the termination of three projects and significant delays in four other projects. Plaintiffs typically filed their court challenges within 120 days. District courts generally reached a decision within one year; appellate court decisions commonly required at least two additional years. In several cases, developers proceeded with construction before final court decisions.

Further research into the effects of judicial review on deployment of renewable energy projects could develop additional information about the specific claims made in court cases and the extent to which these cases relied on the Administrative Procedure Act. Categories of claims could include procedural issues (e.g., failure to consult) or scope of analysis (e.g., failure to consider an adequate range of alternatives).